Jeff Feuerzeig’s “Author: The JT LeRoy Story,” a documentary, offers a complex and deeply fascinating account of a decidedly unusual chapter in recent American cultural history. Its subject was purportedly an HIV-positive teenage male prostitute in San Francisco who became a minor literary celebrity about 15 years ago. His story was that he was the grandson of a West Virginia fire-and-brimstone radio preacher whose rebellious daughter, Sarah, became a truck stop prostitute who sold her son to truckers too, sometimes dressed as a boy, sometimes as a girl.

After landing in San Francisco, and the death of Sarah, JT purportedly sought the help of a psychiatric counselor, Dr. Terrence Owens, who, as he relates in the film, advised writing as a means of therapy. Soon, articles about the boy’s experiences began appearing in various publications under the byline of “Terminator.” After a while, Terminator revealed what sounded like a real name, J.T. Leroy, and published two books of fictionalized memoir, Sarah and The Heart Is Deceitful Above All Things.

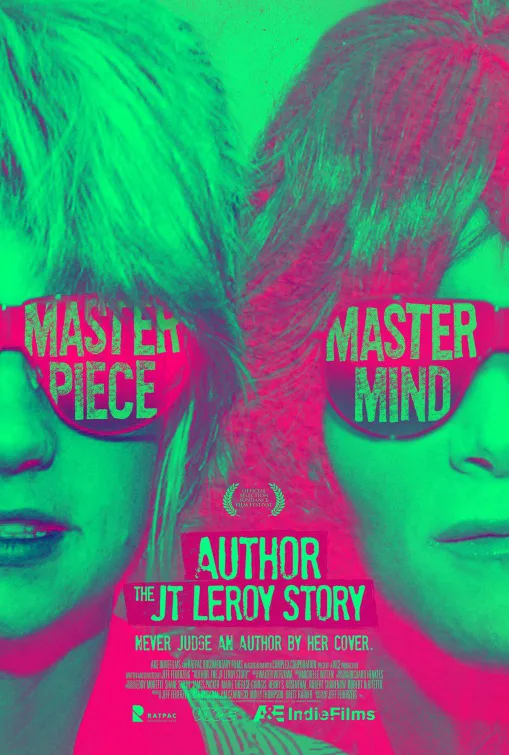

Both books received serious praise in all the right places, and launched JT LeRoy toward celebrity-hood. Prior to this, he had never been seen in public, though a few vague photos had been published. With the demands of fame, he began to appear: a short, androgynous teen always bedecked in a blond wig, floppy hat and big sunglasses. JT at this point said he lived with his manager, a British-accented woman named Speedy who always accompanied him in public. Speedy had a boyfriend named Astor, and together they had a baby and a rock band, in addition to taking care of JT.

JT was avid to know celebrities, and—mainly via telephone—he developed friendships with many. He got career advice from Bono; worked on the TV show “Deadwood” with its creator, David Milch, and on “Elephant” with Gus Van Sant, who said JT deserved part of the Palme d’Or the film won at Cannes. Billy Corgan, Courtney Love and many others were pals and admirers. In “Author,” the extent of the JT cult is indicated by an early-2000s event in New York City where Winona Ryder gushes over their friendship and Lou Reed is among those who read from the young author’s works.

Then it all came crashing down. In 2005, New York magazine charged that JT LeRoy was not a real person but the creation of Laura Albert, a New York-born writer in her 40s. According to this account, which was backed up by further reporting in the New York Times, Albert was the real Speedy, with a fake Brit accent. “Astor” was her longtime boyfriend, musician Geoff Knoop. And the JT who appeared in public was Knoop’s sister Savannah, in wig and sunglasses.

These revelations seemed to consign the career of JT LeRoy to a file labeled “Hoax,” a label that Albert, who appears throughout “Author,” rejects as reductive and unfair. I happen to agree with her, but before going further, I should discuss my particular perspective on the subject.

In the late ‘90s I was writing for the alternative weekly New York Press when I noticed the paper was publishing the writing of one Terminator, who described his life as a teen hustler in San Francisco. I thought the writing was very good as well as fascinating and asked my editor about the author. He passed along my compliments and my phone number to Terminator, which is how our long-distance friendship began.

We talked every week or two, sometimes for an hour or more. At no point did I doubt I was talking to a teenage boy with an authentic Southern accent. He seemed fragile and damaged, very much the product of the life his writings described. But he was also charming, smart, funny and sweet: a delight to talk to, and endlessly engaging. I remember asking him how West Virginia truckers would react when his mother dressed him up as a girl and they discovered he was boy. “Godfrey,” he drawled, “you’d be surprised how many quarterbacks like a cheerleader with a dick.” (He was right: the thought had never occurred to me.)

The period when we were most in touch was when he was writing Sarah (I tried unavailingly to get him to use the title “Lot Lizards”) and he later gave me credit for “midwifing” the book. I did little, really, besides listening to long passages of it and offering comments. The book didn’t need my help; it was, and is, amazing. I knew that during this time JT was in touch with other writers, and “Author” suggests he taped every conversation he had. Writer-friends including Bruce Benderson, Mary Karr and Dennis Cooper are interviewed in the film. (I’m not sorry I wasn’t.)

In 2000, I was about to travel to San Francisco and told JT I’d love to meet him. He seemed panicked and offered various reasons why that wasn’t possible. This didn’t make me suspicious given the extreme shyness and psychological precariousness he’d previously evidenced. A few years later, I snuck into that New York event that included Winona Ryder, Lou Reed, et al., and sat down next to the blond person who’d been introduced as JT There was no reason he should have recognized me as we’d never met. I thought of handing him my business card, but I didn’t because I decided that this person was actually a female (the hips were the giveaway). But it just seemed like further evidence of both JT’s shyness and his wit that he’d have a woman play him in public. When he called me later, I told him I was sorry I hadn’t identified myself. “Don’t apologize,” he laughed. And without missing a beat: “I was having an out-of-body experience that night.” (I missed the chance to ask which body that might have been.)

Feuerzeig, who previously made “The Devil and Daniel Johnston,” and editor Michelle M. Witten deserve credit for one of most the sharply crafted and enthralling documentaries in recent memory. Into the many startling twists and turns of JT Leroy’s career and its aftermath, they weave flashbacks to Laura Albert’s early life, which was troubled enough to have plausibly produced a person who was as damaged as the JT I first encountered and as needful of the writing therapy that Dr. Owens proposed.

When the film debuted at Sundance, some reviewers scorned it for not probing Albert’s account more forcefully or interviewing those who were “fooled” by her about how they feel now. But this is about as silly as suggesting that Errol Morris should have interviewed all of Robert McNamara’s critics for “The Fog of War.” “Author” is a particular kind of documentary: a first-person account of the creation of a myth by its creator. As such, it poses all sorts of questions about the intersection of art, celebrity and psychological disturbance in our media culture, but it also gives us Laura Albert as a shape-shifting artist of astonishing talent, resourcefulness and originality.

When the “truth” about JT came out, I was as devastated as I would be in learning about any friend’s death. But then and now, I never felt I was “fooled,” any more than I’ve felt traduced by any work of art. I felt I had been grandly, amazingly entertained, taken on a once-in-a-lifetime imaginary journey with a truly unforgettable character. And valuably instructed, as regards the various ways one can understand reality. To my mind, JT is still more real than many flesh-and-blood entities I encounter—just as to me Ziggy Stardust is more real than, say, the Electoral College, or Scarlett O’Hara more than Melania Trump.

When all the brouhaha died down, Laura Albert got in touch. She was just as kind and sensitive as JT had been. I told her that, whatever the rest of the world may think, and no matter how many jokes about Charlie Brown and the Great Pumpkin it might provoke, I still believe in JT and always will. She said she understood.