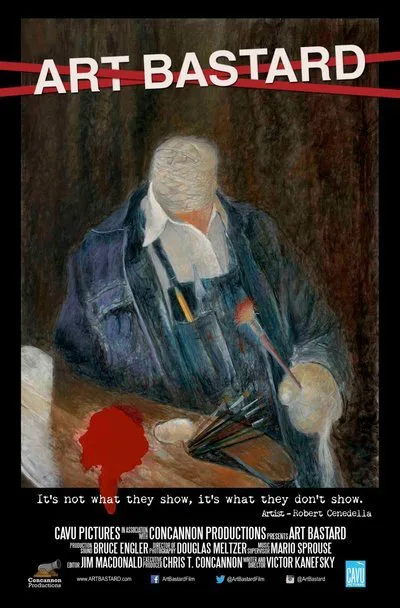

One of the defining moments of artist Robert Cenedella’s life was when he learned at age six that he was illegitimate. Cenedella said that from that point on he felt like an outsider in his own family, thinking, “I’m not really one of them.” Being “not one of them” has also been his relationship with the official “art world,” where he remains virtually ignored. Cenedella’s outsider status seems to suit him just fine. In the mainstream art world, a painting’s artistic worth is determined by the dollar-value attached to it, and Cenedella says, “There is no word to describe my feeling for the art world. I despise it.” “Art Bastard,” Victor Kanefsky’s engaging and thought-provoking documentary about Cenedella, is a beautiful portrait of the man himself, still going strong at age 76, as well as a critique of the art world that has ignored him (and others) because they don’t “fit.”

Cenedella’s gigantic paintings are crammed end to end with people. They show New York City in all its cacophony and chaos (his paintings seem to have sound; you can almost hear people screaming, subway trains roaring by, taxis honking). In works like “2nd Avenue,” “Red Light” and “42nd Street,” Cenedella takes the already-strange urban environment, where you see crazy things happen every day, and twists it into satire, irony and humor. Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending on your perspective), Cenedella started painting during the rise of abstract expressionism, with artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko becoming gigantic stars. Suddenly, “representation” was out. People vanished from paintings. There was no place for Cenedella’s jostling street scenes with their biting satire in that environment. Cenedella says, “Abstract expressionism negated anyone who had a point of view.”

This situation leads to deeper and more urgent questions, questions that course through “Art Bastard” like quicksilver: Who is it that decides what qualifies as art? Who is it that says, “This is ‘in’ now, and that is ‘out'”? And how dare they? Cenedella says that it is “mediocrity [the gallery owners] deciding the fate of geniuses.” Kanefsky’s interview subjects, Cenedella himself, museum and gallery owners, art historians, friends, all testify to the issues in the art world, a world focused more on buying and selling than anything else, where people buy paintings as investments that they hope to cash in in the future. They may not even like the paintings they buy. In that degraded environment, good work, challenging work, or even just work that doesn’t “fit” with what is dictated, randomly, as “in” or “hip,” is ignored entirely.

One of the most fortunate accidents of Cenedella’s life came when he was still a teenager and he enrolled in the Art Students League in New York, landing in a painting class taught by George Grosz, the German artist and caricaturist whose heyday had been in the Weimar Republic. Grosz was a socially conscious and political artist, a vicious satirist, lampooning fat cats, the rich, the powerful. He watched the rise of Nazism and heard the warning bell for what it was. His wonderful work has also suffered from severe official neglect. A troubled man, Grosz was the perfect teacher for a rebel like Cenedella, who had been expelled from high school for not signing a Loyalty Oath, whose father had been targeted by the HUAC and who refused to answer any questions. Cenedella says, “[Grosz] taught me how to draw and he taught me how to drink.”

Cenedella’s inspirations for his own work are people like Grosz, Grant Wood, George Bellows and Rockwell Kent’s illustrations for Melville’s “Moby Dick.” He would go to the Met and stand in front of Pieter Bruegel’s “The Harvesters,” saying, “I could never see enough of it.” (A really helpful choice made by Kanefsky is to end the film with a credit-roll of the paintings mentioned throughout.) The social and political protest art of the 1930s were inspirations to Cenedella, art that portrayed real-life issues like bread lines, racial tension, poverty, unrest. And so Cenedella’s work, as funny and engaging and eye-catching as it is, was perceived as old-fashioned, not as “now” as, say, Jackson Pollock. But Cenedella jokes, “I consider myself a contemporary painter because I am painting today.”

One of the best parts of Kanefsky’s approach is the way he allows the camera to wander through Cenedella’s paintings, moving from face to face to face. The works are so large, so rich with imagery, that they are very difficult (impossible, really) to take in at one glance. The magnifying-glass approach helps illuminate the sheer amount of information in any given painting. Cenedella’s paintings are funny. They’re funny when you look at them from a distance, but they’re even funnier when you get in close. They are personal, political, social. He’s a critic, but he’s not a humorless one. He is in a long tradition of social satirists, caricaturists, absurdists and cartoonists. One of “Art Bastard”‘s greatest assets is that it contextualizes Robert Cenedella’s work, placing him in the proper framework to understand his importance. Another asset is Cenedella himself, a lovely interview subject, an insightful and funny narrator of his own life.

The conservative art world makes decisions on what to show and who to celebrate. It’s the most rigid high school clique on the planet. Cenedella makes it clear that “it’s not what they show that bothers me. It’s what they don’t show.” He wells up with tears when he talks of the death of his mentor, George Grosz, and the fact that Grosz died thinking of himself as a failure. Grosz painted what he saw in his world, and what he saw was disturbing and dismaying. His 1920 “Republican Automatons,” for example, cracks open the edifice of a political and social system with brutal efficiency. Work like that is not ingratiating or flattering to the viewer; it speaks the truth beneath the official version of the truth. Cenedella has also tried to speak the truth beneath the truth in his work and “Art Bastard” is a fitting tribute to him. As Grosz once said, “Great art must be discernible to everyone.”