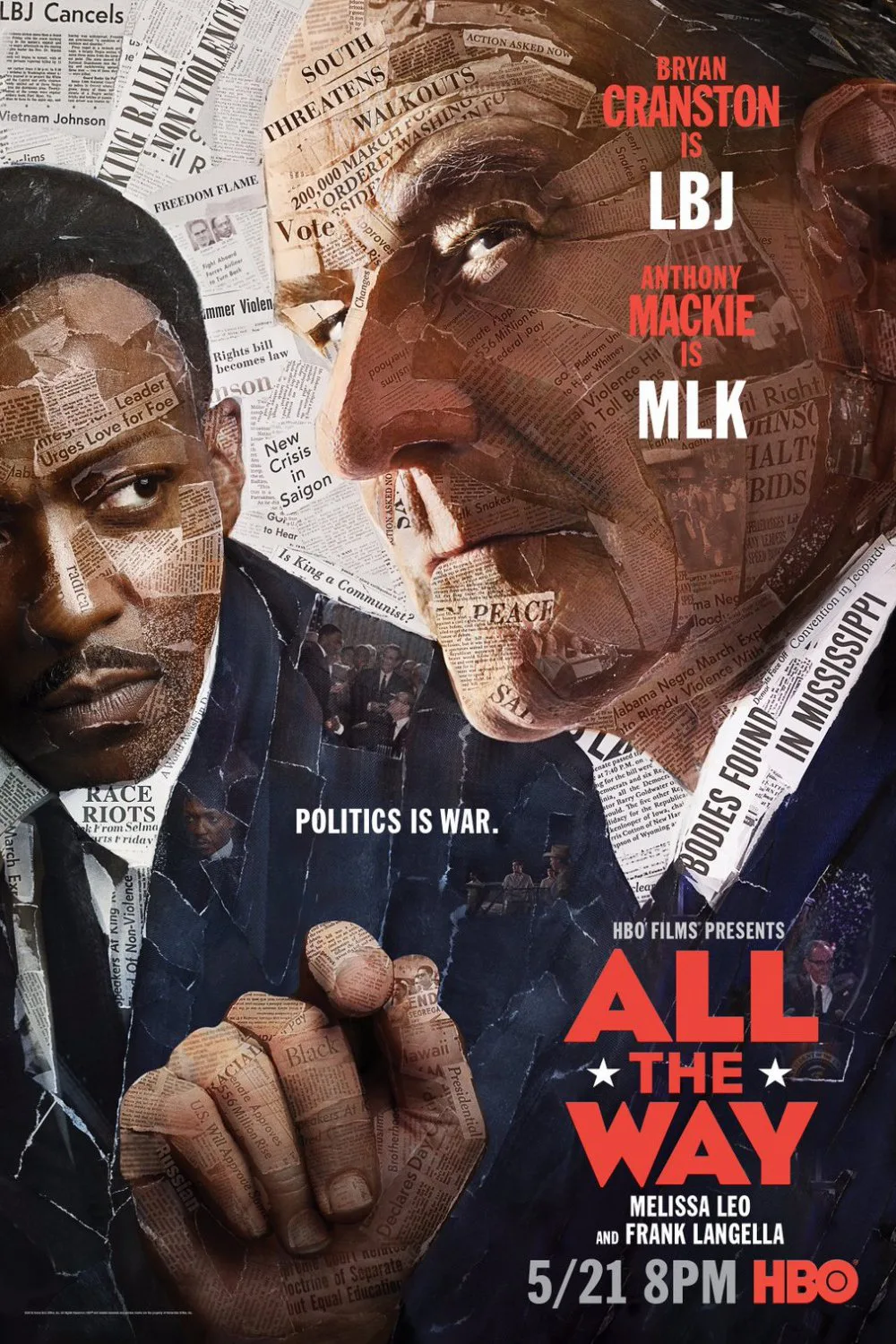

It is perhaps an appropriate election year to remind ourselves that change in this country takes blood, sweat and tears. At a time when the nation feels more divided than ever, it’s healthy to look back at one of the turning points in the political system of the United States, a fight for civil rights that pushed the establishment so hard that it forever reshaped the electoral college. Think about this amazing fact: Before the Presidential election in 1964, Georgia had never voted Republican. They have done so in the last five elections. The “Republican South” wasn’t always so much of a given, and HBO’s “All the Way” makes the case that a lot of this political shift started because Lyndon B. Johnson recognized the importance of civil rights when he ascended to the presidency after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, turning it into the election issue of that year and provoking the ire of a GOP establishment that wasn’t on the right side of history.

This excellent drama, carried by a truly incredible performance from Bryan Cranston, captures the difficulty of the political machine. “All the Way” can be a little frustratingly thin, in that it tries to do a bit too much in 132 minutes, turning complex political figures into “plot device characters” (ones who come into frame, serve their purpose for the protagonist, and exit stage right), but there’s so much worthy of discussion in the piece that “All the Way” never drags. And Cranston should clear some more mantle space for a future Emmy and Golden Globe to sit next to the Tony he won for this role.

Adapted from his play of the same name, writer Robert Schenkkan, working with director Jay Roach, is careful not to make “All the Way” feel like a filmed play. A cinematic score by James Newton Howard, and fluid, complex camera work by Jim Denault help that effort, but it’s the engaging turn by Cranston that really magnifies the source material. One can see why he was so praised on stage (I never saw the play) as he embodies Johnson, diving into both his outlandish behavior (having meetings while on the toilet) and complex moral code. In many ways, it is everything that Cranston’s performance in “Trumbo,” also directed by Roach, was not. While that performance felt like a caricature, Johnson feels well-rounded and complex from minute one of “All the Way.”

In that first minute, Johnson is on Air Force One, with a still-bloody Jackie Kennedy, after her husband’s assassination. He’s going to take the Oath of Office to become the President of the United States. In his first speech as President, Johnson affirms that the Civil Rights bill his predecessor started will be his priority. Johnson’s former mentor and friend Senator Richard Russell Jr. (a perfect and understated Frank Langella) isn’t too happy with this decision, but Hubert Humphrey (Bradley Whitford) embraces the directive, positioning himself to be Johnson’s Vice President in the upcoming election. Most of all, Martin Luther King Jr. (Anthony Mackie) recognizes that he will have to work carefully with Johnson to get what his movement demands from the government.

Concessions start quickly. Johnson learns that unless he removes voting rights from the bill, it won’t pass. From the beginning, Schenkkan and Roach are working with the very core of the political game in how they capture what Johnson knew was and was not possible. While some encourage him to fight for voting rights, he realizes that fair employment and making other discriminatory practices illegal this year is step one, and voting rights is next year. As J. Edgar Hoover (a cartoonish Stephen Root) spies on King to try to get dirt and Lady Bird Johnson (Melissa Leo) stands by her husband’s side, the political stew starts to boil. As the election season heats up, party lines are drawn and unexpected curveballs keep Johnson from an easy path to stay in the White House. Few films have better captured the unpredictability of the campaign season, such as when the murder of a civil rights activists derails his strategy or when the arrest of someone close to him nearly ruins everything. And it’s impossible not to read a bit of commentary into the current political season when Johnson mentions “outside forces conquering and destroying the South by appealing to their racial hatred.” It’s a line that was either prescient to the racial divisions defining this campaign or written for the movie and not the play.

While there’s a lot to like in Schenkkan’s smart script, “All the Way” is really a vehicle for Cranston, and he delivers in ways that make it much easier to forget “Trumbo.” This is such a nuanced take on a character who could be larger than life. He’s got the accent, the bloated ego and all the elements on to which other actor’s would hang the entire performance, but then he shades from there. Right from the beginning, when Johnson is questioning how seriously he’ll be taken as he steps into Kennedy’s shoes, this is an intricate acting turn that’s more interested in character details than caricature. Mackie is good, though MLK plays more of a supporting role here than he arguably should have. But “All the Way” focuses on Johnson’s role in the civil rights movement, not the story of civil rights on the ground in the South, as so deftly captured in Ava DuVernay’s “Selma.”

“All the Way” can be a crowded film, and roles like Hoover & Lady Bird aren’t designed to feel like more than sounding boards for Johnson. As with a lot of stage-to-screen productions, the background players sort of fade into a chorus, but what’s there in the spotlight, center stage, isn’t just a great performance but a formative chapter in our history; one that’s still to be written.