“Perfect!” says Walter Matthau, after Elaine May has dropped her tea cup (twice), her glasses, her purse, her gloves and her composure while trying to master the complexities of a simple tea party. The hostess is dismayed at the damage to her rug, so Matthau deliberately pours his own drink onto it. Then he observes that of all the sexual perversions he has ever witnessed, the neurotic relationship of the hostess and her rug is without doubt the most disgusting. Exit.

Is it any wonder, then, that the enormously wealthy Miss May falls immediately in love with Matthau, whose sole skill, if any, is putting down Turkish rug fetishists? She is, herself, a botanist who dreams of the day when a frond, herb or previously unclassified fern will be named for her. That would be, you see, immortality of a sort, to have a frond of one’s own.

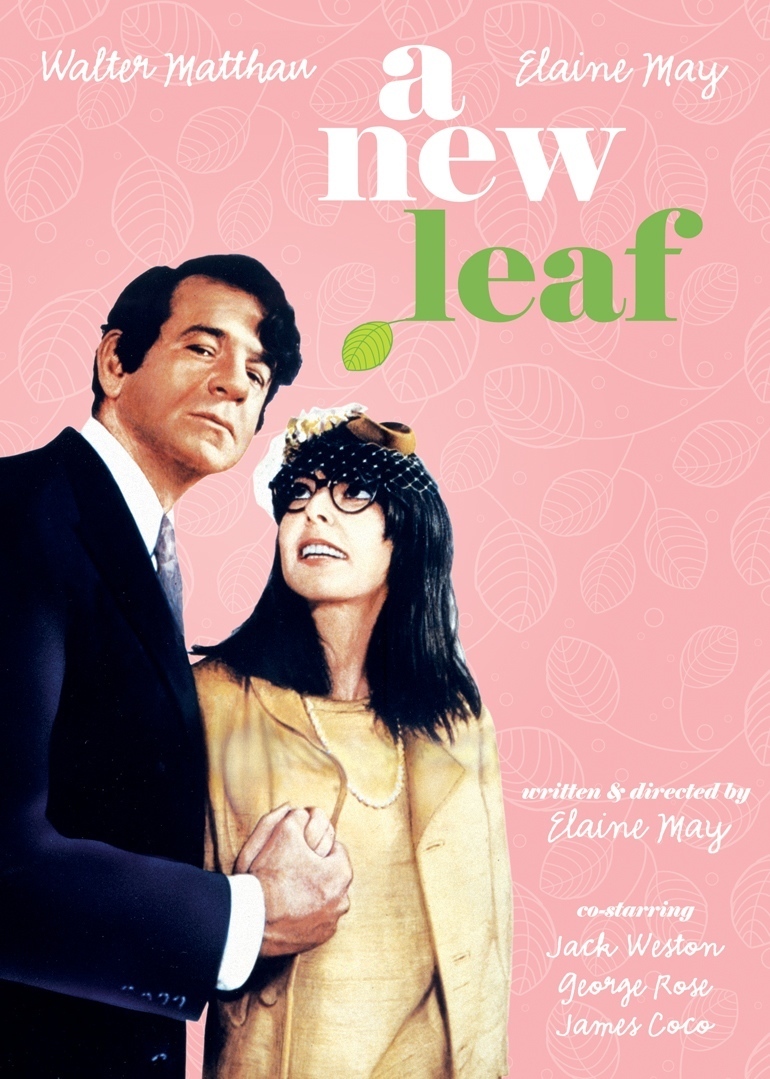

Elaine May’s “A New Leaf ” is a love story about these two people, who are in desperate need of each other even if he doesn’t know it. Matthau plays an aging bon vivant who has squandered his fortune and is told by his butler that he has few choices: Suicide, perhaps, or marrying money. He has no ability or ambition, and work of course would be out of the question. He has dedicated his life to living it comfortably and with style. His butler tells him, as he dons his velvet smoking jacket: “You have preserved in your own lifetime sir, a way of life that was dead before you were born.”

To carry it still further, he borrows $50,000 for six weeks from his rich uncle, a sort of gay Rabelaisian played by James Coco, who spends most of his day eating, drinking and employing a transistorized pepper mill. Matthau sets out on a search for the right potential wife, with no results until Miss May drops her teacup and he suspects that she may be so incompetent, even dumb, as to marry him.

Their courtship involves finding out about each other’s tastes. He savors rare French vintages, for example, and she likes Mogen David and soda, with a drop of lime juice. And so on. For their wedding night, she dons a Grecian gown, inadvertently sticking her head through the armhole. He attempts to readjust her, and as she struggles within the gown for about two minutes you hear more laughter than I’ve heard in any theater since “The Producers” (1968), which is my yardstick for these matters.

“A New Leaf” is, in fact, one of the funniest movies of our unfunny age. Miss May is reportedly dissatisfied with the present version; newspaper reports indicate that her original cut was an hour longer and included two murders. Matthau, who likes this version better than the original, has suggested that writer-director-stars should be willing to let someone else have a hand in the editing. Maybe so. I’m generally prejudiced in favor of the director in these disputes.

Whatever the merits of Miss May’s case, however, the movie in its present form is hilarious, and cockeyed, and warm.