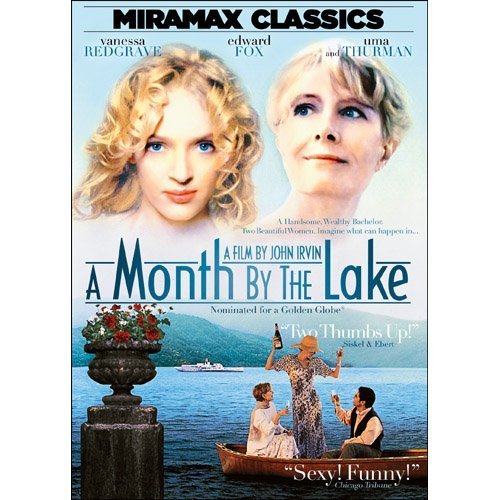

“A Month by the Lake” is a sly romantic comedy about a collision of sex, ego, will and pride, all peeping out from beneath great thick layers of British reticence. Its delights are wrapped in a lavish production in a beautiful time and place – Italy’s Lake Como, in the spring of 1937; it’s another one of those movies, like “Enchanted April” and “Only You,” about perfect places for a holiday.

In this case, however, much of the appeal comes from the characters who inhabit it, and who bring a style, eccentricity and humor to it that is unlikely to be supplied by modern tourists. Miss Bentley (Vanessa Redgrave) is a British spinster of a certain age, who is at the absolute peak of physical and mental perfection. All she needs is more self-confidence (or does she have it, and is she playing a subtle game?). On the first day of her month’s vacation in an elegant lakeside hotel, she sees Maj. Wilshaw (Edward Fox), a handsome man whose elegant haberdashery is set off by a battered brown felt hat, worn at a reckless angle.

She likes his looks. Specifically, his ears: “He has the ears of a kind and gentle man.” She tells him so. I have written that a man will believe almost anything a woman tells him, if she begins with compliments. This does not apply so much to the ears. The major is, nevertheless, intrigued, and invites her to join him for a drink at seven. She is late – so late he has already gone in to dinner. Was she deliberately late? The movie is elusive. She pursues him, and yet at crucial moments she drops out of the chase.

Miss Bentley has a scenario of her own. She observes that the major always carries two tennis rackets, and offers to play a set with him. Now comes the movie’s perfect moment, as Redgrave uses indescribable body language to portray a woman who, with all the awkwardness and ungainliness in the world, is a superb player and cannot help humiliating the major on the court. The sight of her hiking up her skirts and tucking them out of the way is worth the price of a ticket.

Within a few days, the major announces, regretfully, that he must return to England. Miss Bentley is devastated; this throws her timing off. As he is leaving the hotel, however, he is shamelessly flattered by Miss Beaumont (Uma Thurman), the nanny of some rich Americans, who even plants a kiss on his face. “That was cruel,” Miss Bentley tells her. Miss Beaumont, who lives in the moment and relishes her power over men, couldn’t care less. Her gesture has its effect: Soon poor Maj. Wilshaw appears again at the hotel, dragging his libido and pride with him, under the impression that Miss Beaumont really cares for him.

Edward Fox is an elegant and handsome man, but he is not particularly tall, and there is a scene here where Uma Thurman literally towers over him (her name is “Beaumont” – beautiful mountain – for a reason). Observe a scene where the major, having returned in hopes that the young nanny will fall to him, finds himself pursuing her. He would rather run, but dignity requires him instead to walk stiffly, as quickly as he can – his arms flapping behind him. He cannot match her long-legged stride. It is a moment that says more about his character than any words would dare to.

Vanessa Redgrave is tall, too, but able to lean forward and search for signs of thought in the hapless major’s face.

What is intriguing about the film, written by Trevor Bentham and directed by John Irvin (“Turtle Diary,” “Widow’s Peak”) is that it never concedes it is about sex. Flirtation itself is the point of the game. Consider the scene where Redgrave and Fox go swimming – her body magnificent in a sleek black costume – and it would seem that they must fall into one another’s arms. The movie understands that flirtation, indefinitely prolonged, is much more interesting to an audience than seduction, quickly consummated. It is always wise to give an audience something to look forward to, rather than wistful memories.

Words, indeed, remain largely unspoken in this world. The whole movie depends upon British style, reserve, codes and reticence – even the last awkward embrace. They are certainly capable of embracing more warmly. They have the skill, and even the occasion. They simply do not feel free to. Perhaps they believe it is better to spend the rest of one’s life alone than to allow, for even a moment, a violation of one’s personal style and standards. Perhaps they are right. Certainly without style and standards there would be no movie, no story, no Miss Bentley, no Maj. Wilshaw.