Ben Wheatley’s historical drama “A Field in England,” about a group of men wandering the countryside during the English civil war, is at once too little and too much. In the manner of certain bawdy, bloody works of 1960s and 1970s art cinema, not to mention psychedelic midnight flicks from the same era, it’s all over the place and often seems to be trying too hard to accomplish goals it can’t quite articulate. It seems to be at least partly about the absurdity of entitled royalty and the ingrained cruelty of the class system. The characters, mostly deserters who’ve fled either their military obligations or their servitude to a specific master, fall under the dark spell of O’Neil (Michael Smiley), an avowed necromancer who terrorizes the rest into helping him find a buried stash of gold while they’re under the influence of hallucinogenic mushrooms.

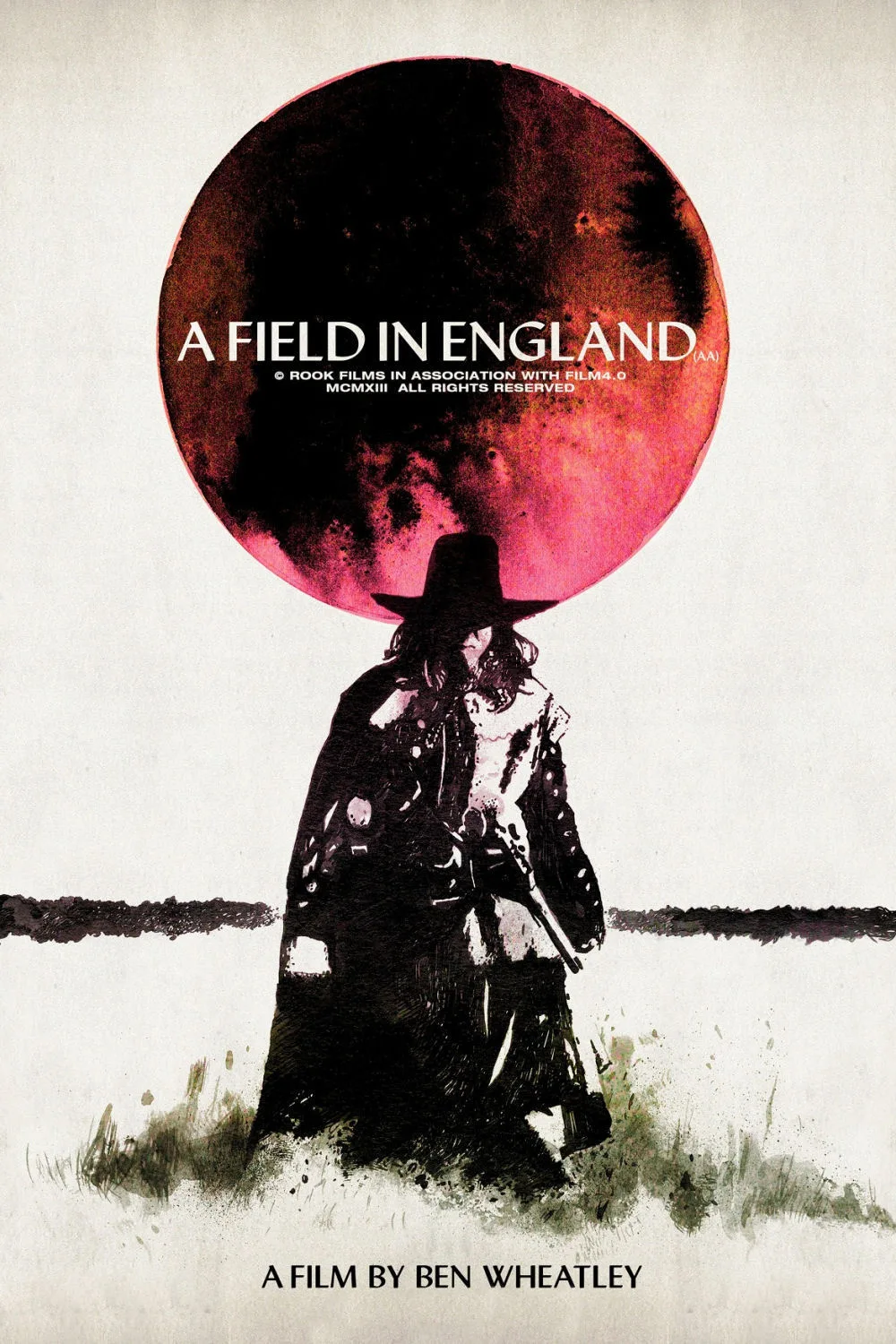

But the plot and theme aren’t what you remember later; they aren’t even what make an impression as you’re watching “A Field in England.” Written by Wheatley (“Down Terrace,” “Kill List“) and Amy Jump, and shot in mostly handheld black-and-white wide-screen images, this is a deeply, at times exclusively visceral film. It aims to wring out, mind-eff and visually beat up its viewers, and cast a malevolent spell in the process. There’s even a pre-credits warning that the film you’re about to watch contains extensive strobe effects, and boy, does it ever. It also contains a solid minute or two of guys pulling on a rope while grunting, and a bit in which a character growls and groans in agony while trying to defecate in a field, and a sequence wherein men scream and scream and scream and scream in agony, at top volume. Not a great first date film, in other words, unless your date is Mel Gibson.

And yet at the same time, the movie’s characters are fascinating—particularly the scholar Whitehead (Reece Shearsmith), who holds up his meager book learning as a great depth of knowledge. Whitehead seems hopelessly in thrall to the necromancer, who uses him as a sort of divining rod to find the treasure, and whose “magic” is indistinguishable from the effects of the mushrooms that the others wolf down. And Wheatley’s style is so original—at times almost indescribably so—that its blind alleys and excesses, too-muchness and too-littleness seem of a piece. There’s something to be said for a film that plainly could not care less what anyone thinks of it. “A Field in England” is not timid or focus-grouped, and its grimy, gritty, often nasty aspects are part of a tradition that reaches way back to “The Canterbury Tales,” a fact that might be easier to see if Wheatley’s style weren’t so aggressively avant-garde.

Added to which, there’s context for the touches that at first seem random or overcooked. This is, after all, a movie in which half the story occurs while major characters are under the influence of hallucinogens, picturing their colleagues moving in super-slow motion or staring blankly at an ever-expanding hole in the sky where the sun once was. Contrary to the characters’ chief worry, though, in this world God is not dead, blind or indifferent. He’s directing, and like flies to wanton boys, he will smite men for His sport.