The old golden age Warner Bros. crime dramas knew something that most modern movies have forgotten: Heroes are great, but a movie is only as good as its villain. John Frankenheimer’s “52 Pick-Up” provides us with the best, most reprehensible villain of the year and uses his vile charm as the starting point for a surprisingly good film.

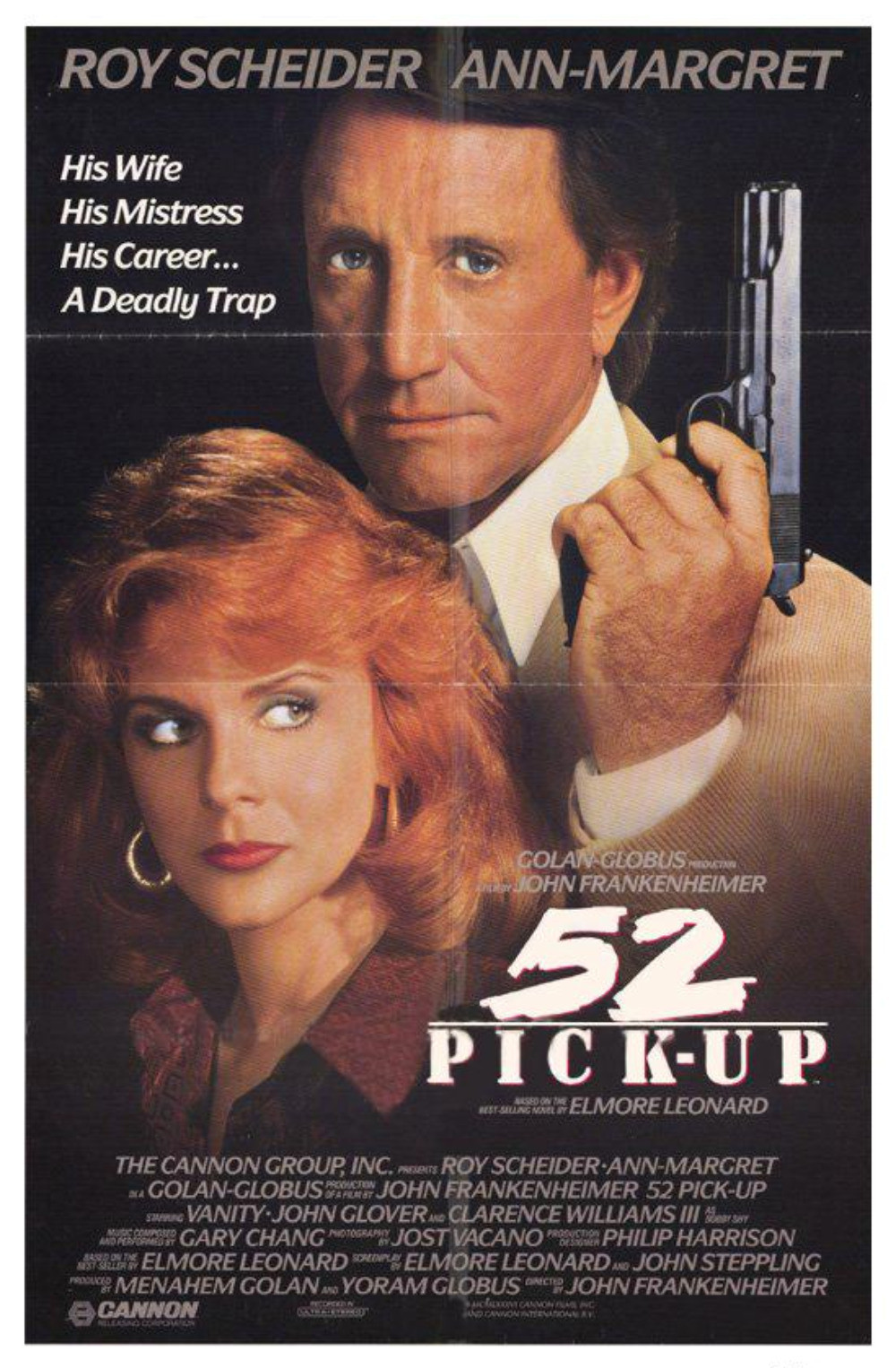

The villain’s name is Raimy, and he is played by John Glover as a charming blackmailer with the looks of an aging British juvenile and a conscience with parts on order. He tries to pull a slick job on a rich businessman named Harry (Roy Scheider). He shows him videotapes of an affair Harry is having with a topless dancer. He wants $110,000. Harry thinks it over, decides not to pay and confesses everything to his wife, Barbara (Ann-Margret). In a scene of powerful understatement she says she had guessed the truth for a long time but she just doesn’t know why he had to tell her. Then Raimy turns up with another videotape. This one shows the topless dancer being murdered with Harry’s gun.

This plot is not startlingly original (although there are some unexpected developments later in the film). What makes it special is the level at which it is told. The screenplay is based on an Elmore Leonard novel and retains Leonard’s gift for terse, colorful dialogue.

It also isolates the key ingredient in Leonard’s best novels, which is the sight of a marginal character being pushed far beyond his capacity to cope. In “52 Pick-Up,” there are three such characters, and by the end of the movie they are all desperately confused and frightened.

One is Raimy, a well-dressed sleazebag who makes porno movies and is capable of cold-blooded murder but caves in completely at the thought of his own destruction. One is Harry, an ordinary amoral businessman who rises to the challenge and figures out a way to outsmart his blackmailers by using their character defects against them. The third is a sweaty little guy named Leo (Robert Trebor), who works for Raimy and went along with the crime but, holy God, never figured anyone was actually going to get hurt.

The problem with so many action adventures is that nobody in the movie ever seems scared enough. People are getting killed in every other scene, and they stay cool. If the movies were like real life and this kind of torture and murder were going on, everybody would be throwing up every five minutes – like they do in John D. MacDonald’s novels. “52 Pick-Up” creates that sense of hopelessness and desperation, and it does it with those three performances – three guys who are in way over their heads and know it all too well.

There are three other good performances in the movie, by Ann-Margret, Vanity and Clarence Williams III (as a black pimp who is a lot more experienced about violence and death than his cheerful white partners). Is it still necessary to be surprised when Ann-Margret is good in a role, as if she were still making “Viva Las Vegas”? She has grown into a dependable serious actress, and here she does a delicate job of finding the line between anger at what her husband has done and pride in how he is trying to fix it. Vanity has a smaller role, as a prostitute with crucial information, and she does what all good character actors can do: She gives us the sense that she’s fresh from intriguing offscreen action.

The story of “52 Pick-Up” is basically revenge melodrama. No thriller fan is going to be very astonished. What matters is the energy level and the density of detail in the performances. This is a well-crafted movie by a man who knows how to hook the audience with his story; it’s Frankenheimer’s best work in years. And if we can sometimes predict what the characters will do, there’s the fascination of seeing them behave like unique and often very weird individuals. They aren’t clones. I have gotten to the point where the one thing I know about most thrillers is that I will not be thrilled. “52 Pick-Up” blind-sided me.