The German director Oliver Hirschbiegel impressed viewers the world over with his brutal and psychologically astute 2001 film “The Experiment,” but it was with 2004’s “Downfall,” a spectacularly effective picture about Hitler in his last days, that he not only made his reputation as a world-class filmmaker but also inadvertently created an Internet meme.

Yes, every time some wise guy puts a subtitled scene of Hitler reacting badly to something that has nothing to do with Hitler pops up on YouTube, it’s using “Downfall” as the source material. And yet—and this is a testimony to the power of that movie—one can to this day watch an unmodified “Downfall” and be engrossed and appalled by its whole, and by that scene. (The fact that Hitler is being played by the amazing Bruno Ganz is a bit plus here of course.)

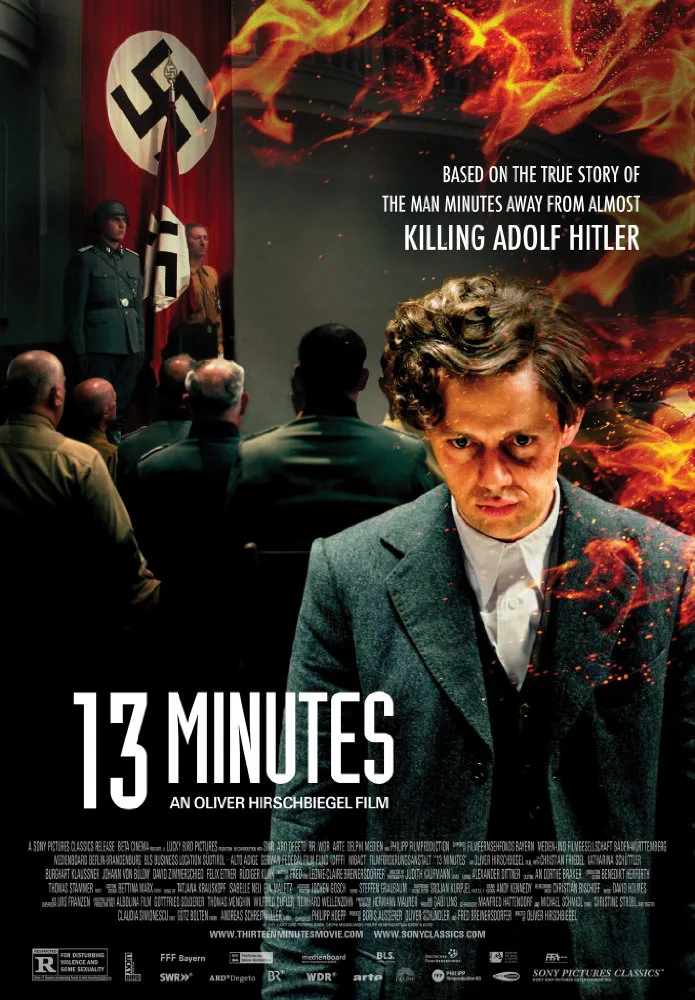

Hirschbiegel’s career has had some dips since then. A curious 2007 rethink of “Invasion of the Body Snatchers,” titled “The Invasion,” was a fever-paced head-scratcher. His 2013 Princess Diana biopic proved a massive miscalculation. A cynic might say that after that disaster a revisitation of German history on the level of “Downfall” might be an apt way to revive a damaged career. But “13 Minutes” is too good on its own terms to support such a reading. It’s a genuine achievement on an inexhaustible subject.

The movie begins with its lead character, Georg Elser (Christian Friedel) rigging a bomb into a wall. It’s a big one, too; he’s packed at least a dozen sticks of dynamite in it. He then rigs a timing mechanism, and the camera dollies out to show a table with a placard on it reading “The Fuhrer’s Chair.”

It’s 1939, six years and change since Hitler took power. A few months ago, Britain and France declared war on Germany. The bomb is timed to go off on November 8, the anniversary of the-now-Fuhrer’s failed Beer Hall Putsch. And so it does—13 minutes after Hitler leaves the packed beer hall where he addressed a friendly crowd. Many died, many were injured, but Hitler escaped. And was infuriated.

Elser seems an unlikely assassin. True, he looks appropriately panicked when he is apprehended shortly after the explosion, but when the movie flashes back to 1932, and his life in a village by Lake Constance, he’s a cheerful accordion player and woodworker. One of the most effective aspects of the movie is its depiction of how the Nazi poison seeped into the provinces, abetted by bigots who recognized that der zeit was now on their side. One morning Elser is walking through the village square with a young boy, who parrots some anti-Semitic gossip he heard from his father. “When did you get to be a moron all of a sudden,” Elser says jokingly to the little boy. He hasn’t much time to remain cheerful.

While he describes himself as non-political to his Nazi torturers, he participates in some resistance, keeping lookout for friends painting anti-Nazi graffiti. He lives dangerously in other respects too, having an affair with a married woman, Elsa (Katharina Schüttler) at whose house he eventually boards. These scenes are interspersed between bouts of VERY enhanced interrogation at the hands of the Nazis, and there’s a behind-the-scenes intrigue too. SS honcho Heinrich Müller (Johann von Bülow) insists to police chief Arthur Nebe (Burghart Klaußner) that a full confession is necessary; as Germany goes to war, Goebbels and Hitler are both eager to bolster a conspiracy/martyrdom narrative. Once the Nazi’s dangle Elsa and her safety before Elser’s eyes, the confession, which he had been withholding despite gruesome, grisly torture (which is depicted in some detail), comes quickly. The psychological gamesmanship comes courtesy of Nebe, who’s the “good German” for the purposes of this scenario. (The film later reveals what those who know a little about the Third Reich are aware of: that Nebe was part of a subsequent assassination attempt against Hitler in July 1944. For all that, there is some substantial doubt in historical circles as to just how good of a good German he was.) The Nazis want Elser to admit to a conspiracy, but he insists, and the film shows, that he was a man alone.

He insists this was the case, and the reason he gives to his interrogators is simple: “Nobody would have joined me.” Looking at Germany from the end of World War I all the way to the beginning of the next World War, one is frequently moved to ask, “Why didn’t anybody do anything?” “13 Minutes” offers, in a more or less conventional narrative form, some tentative answers to that question, all of them uncomfortable.