It’s hard to choose a single moment that represents the career of Robin Williams, who was found dead this morning of an apparent suicide at 63. Somehow they all seem representative. The Chicago-born, Michigan-raised actor’s performances shaded antic clowning with deep melancholy, and vice versa. There were flashes of anarchic joy in his grimmest roles, and moments even in his most outwardly featherweight performances when it seemed as though a cloud had passed across his face. Last seen on TV in “The Crazy Ones,” a CBS series set at a Chicago ad agency, Williams battled drug problems and depression throughout his life. Although he had crests and troughs, the light never traveled far from the darkness or the darkness from the light. Like Jack Lemmon, you could believe Williams as a man standing on a ledge or walking on air.

That was the most surprising and often haunting thing about Williams: that sense that when he unleashed the full force of his talent—chasing a spark of inspiration as it hopped from neural pathway to neural pathway like a speed-demon driver changing lanes; rattling off free-associative thoughts that were sometimes connected by shared words or images or vowel sounds; pacing or racing while yammering and gesturing as if his whole being were taking dictation from his subconscious—he was reaching out to the audience and running away from something.

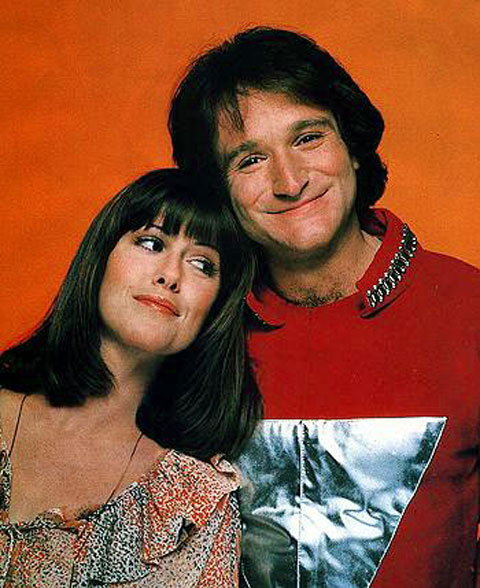

“He could make everybody happy but himself,” said Garry Marshall, who cast Williams in a star-making role as Mork from Ork on ABC’s “Happy Days” and its long-running spinoff, “Mork & Mindy.” Whether playing comedic or dramatic roles or doing standup routines or goofing around on talk shows, he never stayed in one mode for long. And it wasn’t just gradations of fun. You always sensed the darkness lurking. He could be sweet or silly for a while, or light and sweet; then you’d get a flash of anger or bitterness that seemed to erupt from nowhere and that did not seem fake, and then he’d slip back into sweet or silly, and make everyone laugh again.

“When he appeared on the Jonathan Ross show earlier this summer, he’d been vintage Williams, hyperactive to the point of deranged, ricocheting between voices, riffing off his internal dialogues,” wrote The Guardian’s Decca Aitkenhead in a 2010 profile pegged to “World's Greatest Dad,” a pitch-black comedy with unbearably painful dramatic passages, many of which revolve around a suicide note. “Off-camera, however, he is a different kettle of fish. His bearing is intensely Zen and almost mournful, and when he’s not putting on voices he speaks in a low, tremulous baritone–as if on the verge of tears–that would work very well if he were delivering a funeral eulogy.” Anyone who knew Williams or spoke to him for any length of time or simply studied the man sensed this, and understood it. Somehow none of it seemed incongruous or inappropriate because he was Robin Williams, and Robin Williams was everywhere and everyone at once, look out.

His first indelible character, Mork from Ork, was a one-off supporting character on “Happy Days,” an extraterrestrial who battled the show’s king of cool, the leather jacketed Fonzie (Henry Winkler). Producer Marshall was so impressed with Williams’ hair-trigger imagination that he built a spinoff around him, “Mork and Mindy.” Mindy, the human roommate, foil, and future love interest played by Pam Dawber, set the template for a lot of his leading ladies and sidekicks, looking askance at his wild clowning; what else could a non-genius do but gape at a human spectacle?

The show was even more of a situation comedy than most sitcoms, mainly because of who its star was. A man with Williams’s freewheeling brain might’ve had trouble staying on script anyhow—he modeled his standup style on his mentor and friend Jonathan Winters—but at the time he was also feeding a prodigious cocaine habit, one he’d joke about and ruminate on as he got older (“Cocaine is god’s way of telling you you are making too much money,” he said in “Robin Williams Live at the Met”). He also drank too much. If he’d kept going like that, he might have completely lost it and started looking and sounding like the incomprehensibly babbling title character of the live-action cartoon “Popeye,” his first really memorable film role. He said he got sober in 1983 and stayed sober for 20 years, until he cracked while filming “Insomnia” (great performance as a possible psychotic killer) on location in Alaska, but there were relapses and treatments and apologies; anybody who’s dealt with these often-intertwined problems, substance addiction and depression, knows you don’t so much beat them as beat them back.

Or harness them. Like many other great stand ups who were also fine dramatic actors, Williams dove into darkness in many of his best roles. He never seemed to be having to imagine his way into the mindset of people who had numbed themselves with chaos (like his character in “The Fisher King,” who lost his wife in a random shooting and became convinced he was a knight on a holy quest) or routine (like the meek doctor in “Awakenings,” or the title character in “The World According to Garp,” whose opening credits song, “When I’m 64,” will pierce more deeply now).

Despite “Garp,” a lovely adaptation of a book some thought unadaptable, it took a while for him to be taken seriously as a dramatic actor, and an equally long time for one of his films to hit big. He crossed both achievements off his list after 1987’s “Good Morning Vietnam,” in which he played a character loosely based on Vietnam-era Armed Forces Radio DJ Adrian Cronauer—so loosely that it was as if Robin Williams had been time-warped into 1967 Saigon with his “Tonight Show” couch routines intact. (In one bit, he connects “The Wizard of Oz” to the American occupation of Indochina, chanting, “Ho-ooooh-OH…Ho Chi Minh!”) The film was the perfect merger of formulaic Hollywood comedy-drama beats (Williams’ Oscar moment was the scene where Cronauer bids farewell to departing soldiers he’s just entertained, telling each of them, “You take care”) and Williams’ by-then-patented brand of riffing (director Barry Levinson reportedly left many of Cronauer’s DJ booth scenes blank, save for once sentence: “Robin does his thing”).

“Vietnam” was so successful that Williams strove to recapture it throughout the next decade, in a series of comedies (some amusing, others awful) that cast him as a grinning id figure sent to liberate the world from its psychic shackles. The best of these were “Dead Poets Society,” which transplanted his standup-style riffing to the English classroom in a 1950s prep school filled with repressed young men who had to be instructed to seize the day; the aforementioned “The Fisher King,” playing a Manhattan-based, basement-dwelling Sancho Panza to Jeff Bridges’ reluctant and sour Don Quixote; and Disney’s cartoon feature “Aladdin,” which arguably put Williams, at long last, in the role he was born to play: a purple genie that re-formed itself to incarnate any person, creature or concept Williams’ motor-mouth could invoke. (“Can your friends do this?” he sang. “Do your friends do that? Do your friends pull this/Out their little hat?”)

For a long stretch, Williams alternated Holy Fool roles with comic liberator parts (combining the two in his ’90s nadir, “Patch Adams,” about a doctor who believed laughter was not just the best medicine, but a substitute for actual medicine). Occasionally he’d toss in a heavy-makeup tour-de-force for variety (“Mrs. Doubtfire” had its moments; “Bicentennial Man” really didn’t), but for a while there was a growing sense that Williams’ instincts had become too calculated and the material too transparent.

His secret career salvation came in in 1990’s “Awakenings,” in which he played a soft-spoken, emotionally recessive psychologist opposite a much showier Robert DeNiro as a comatose patient made lucid by medicine. Six months later he had a tiny role as Cozy Carlisle, the disgraced psychiatrist in Kenneth Branagh’s time period-hopping murder mystery “Dead Again.” The performance was un-billed, but Williams brought corrosive anger to his few minutes, puffing on cigarettes while sitting in a meat freezer, and warning Branagh’s private eye hero that people are either smokers or nonsmokers, and people who claim to be “trying to quit” are “basically pussies who cannot commit.” Williams had been a comic leading man with a dramatic streak for over a decade at that point, but in these two very different movies, one could glimpse a possible third act in his career, as a character actor.

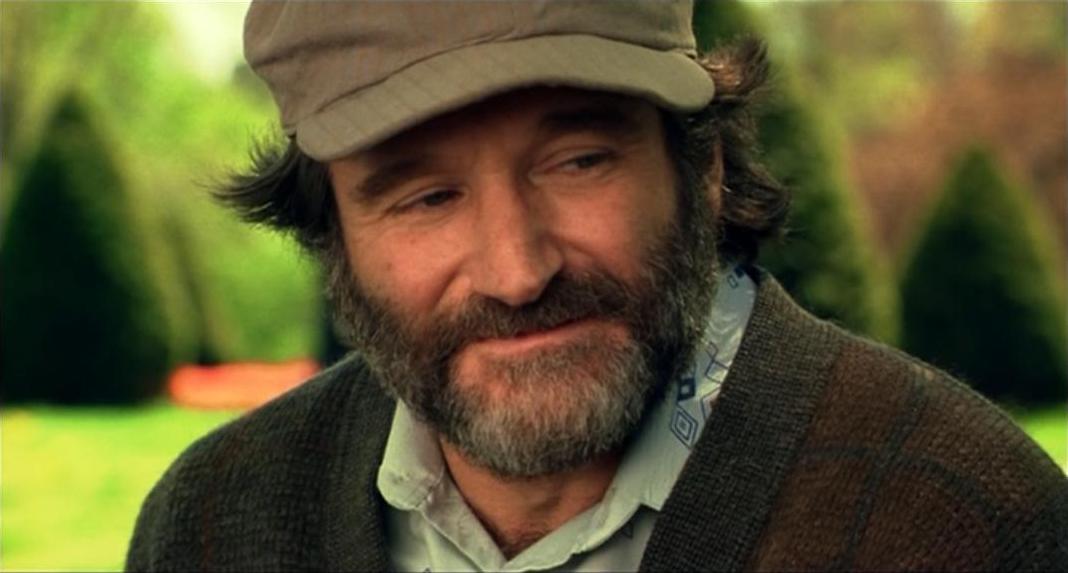

He became a very good one soon afterward, proving himself in roles that seemed ill-suited to the alien in the bright shiny jumpsuit on “Mork & Mindy” who, upon learning that eggs were unhatched baby birds, tossed one in the air, exclaiming, “Fly! Be free!” Williams was chilling as actual or possible murderers in “Insomnia” and “One Hour Photo” and as the hateful showbiz burnout in “Death to Smoochy” (basically “All About Eve” but with raunchy kids’ show hosts) and as President Dwight D. Eisenhower in last year’s “The Butler.” He won his only Oscar as a supporting player, in 1997’s “Good Will Hunting,” playing a community college professor moonlighting as a therapist at the request of an old college roommate.

A lot of people mock “Hunting” as a Hollywood bastardization of therapy, in which a troubled character (Matt Damon’s janitor/math genius/orphan) finally starts to overcome crippling self-doubt and class resentment. There’s some truth to the criticism, and yet the film still works—not just because of Damon and Ben Affleck’s ambitiously multilayered script and Gus van Sant’s precise direction (it’s a romance, a drama, a buddy picture and an inspirational fable all at once), but because the central relationship between the hero and Williams’s Sean Maguire, who understands Will’s pain because he lost his wife to cancer, feels raw and true.

“You don’t know about real loss, ’cause that only occurs when you’ve loved something more than you love yourself,” he tells Will—one of the film’s many devastating moments. Another is the climax, the movie’s breakthrough moment, when Sean reveals that, like Will, he was a victim of childhood abuse, and that he needs to realize that it wasn’t his fault. “It’s not your fault,” he keeps repeating to Will, calmly, over the boy’s increasingly desperate objections. “It’s not your fault. It’s not your fault.”

“The tears of the world are a constant quantity,” wrote Samuel Beckett in “Waiting for Godot,” which Williams starred in during a 1988 Lincoln Center production. “For each one who begins to weep somewhere else another stops. The same is true of the laugh.”