John Irving’s best-selling novel, The World According to Garp, was cruel, annoying, and smug. I kept wanting to give it to my cats. But it was wonderfully well-written and was probably intended to inspire some of those negative reactions in the reader. The movie version of Garp, however, left me entertained but unmoved, and perhaps the movie’s basic failing is that it did not inspire me to walk out on it. Something has to be wrong with a film that can take material as intractable as Garp and make it palatable.

Like a lot of movie versions of novels, the film of Garp has not reinterpreted the material in its own terms. Indeed, it doesn’t interpret it at all. It simply reproduces many of the characters and events in the novel, as if the point in bringing Garp to the screen was to provide a visual aid for the novel’s readers. With the book we at least know how we feel during the saga of Garp’s unlikely life; the movie lives entirely within its moments, keeping us entirely inside a series of self-contained scenes.

The story of Garp is by now part of best-selling folklore. We know that Garp’s mother was an eccentric nurse, a cross between a saint and a nuisance, and that Garp was fathered in a military hospital atop the unconscious body of a brain-damaged technical sergeant. That’s how much use Garp’s mother, Jenny Fields, had for men. The movie, like the book, follows Garp from this anticlimactic beginning through a lifetime during which he is constantly overshadowed by his mother, surrounded by other strange women and women-surrogates, and asks for himself, his wife and children only uneventful peace and a small measure of happiness.

A great deal happens, however, to disturb the peace and prevent the happiness. Garp is accident-prone, and sadness and disaster surround him. Assassinations, bizarre airplane crashes, and auto mishaps are part of his daily routine. His universe seems to have been wound backward.

The movie’s method in regarding the nihilism of his life is a simple one. It alternates two kinds of scenes: those in which very strange people do very strange things while pretending to be sane, and those in which all of the dreams of those people, and Garp, are shattered in instants of violence and tragedy.

What are we to think of these people and the events in their lives? The novel The World According to Garp was (I think) a tragicomic counterpoint between the collapse of middle-class family values and the rise of random violence in our society. A protest against that violence provides the most memorable image in the book, the creation of the Ellen James Society, a group of women who cut out their tongues in protest against what happened to Ellen James, who had her tongue cut out by a man. The bizarre behavior of the people in the novel, particularly Garp’s mother and the members of the Ellen Jamesians, is a cross between activism and insanity, and there is the clear suggestion that without such behavior to hold them together, all of these people would be unable to cope at all and would sign themselves into the nearest institution. As a vision of modern American life, Garp is bleak, but it has something to say.

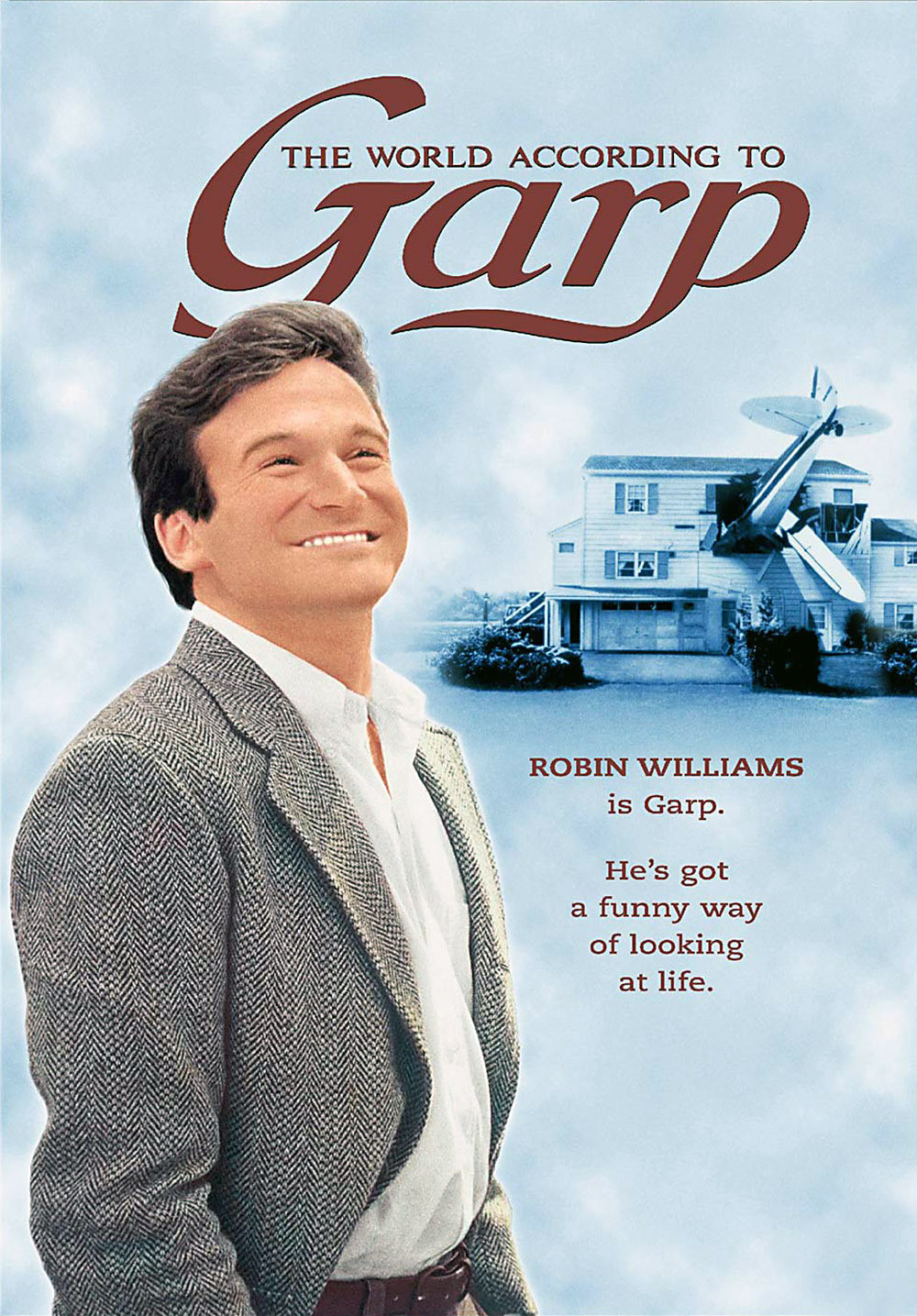

The movie, however, seems to believe that the book’s characters and events are somehow real, or, to put it another way, that the point of the book is to describe these colorful characters and their unlikely behavior, just as Melville described the cannibals in Typee. Although Robin Williams plays Garp as a relatively plausible, sometimes ordinary person, the movie never seems bothered by the jarring contrast between his cheerful pluckiness and the anarchy around him.