Journalist Mark Harris got a lot of attention for his 2008 book “Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood”, which uses the films vying for the 1967 Best Picture Oscar (“The Graduate“, “Bonnie and Clyde“, “Guess Who's Coming to Dinner“, “Doctor Dolittle” and “In the Heat of the Night”) as a lens into the changing world of Vietnam-era Hollywood filmmaking.

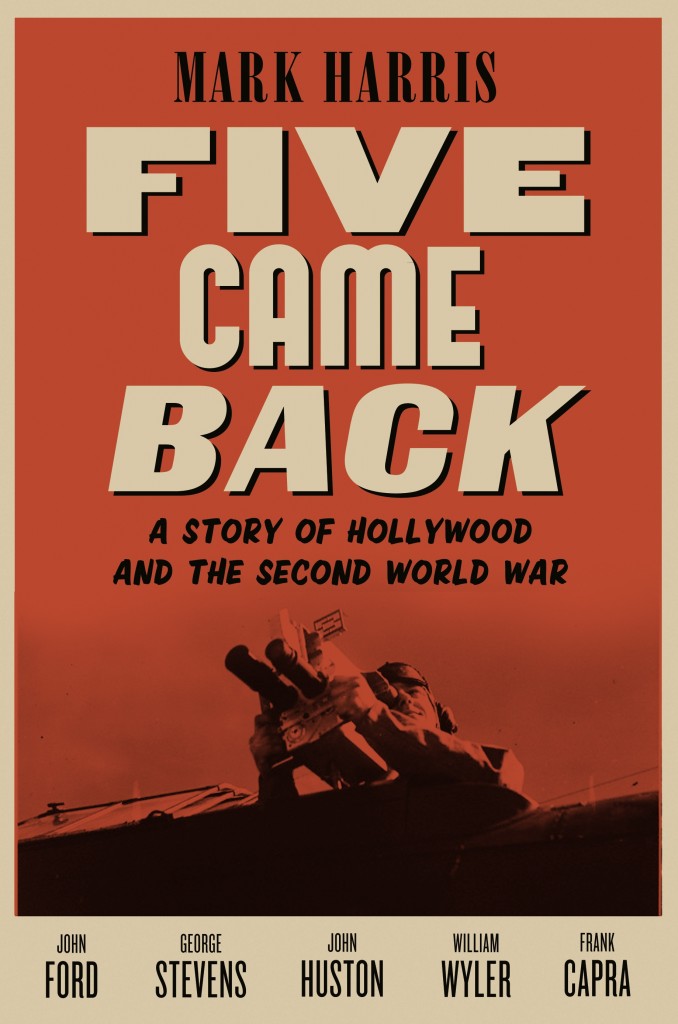

Now Harris has turned his attention to an earlier era, in which Washington enlisted Hollywood storytellers in the war effort, hiring them to make motivational films and documentaries, and record history through artists’ eyes. In “Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War”, Harris examines the wartime work of Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, George Stevens and William Wyler, and reveals how the men shaped the war’s messages and vice versa. The result is a detailed chronicle of artistic and social change during a crucial period of history, as well as a big-tapestry ensemble drama about five talented, complicated men making their way in the world. — Matt Zoller Seitz

How much of the story did you know before you began work on the book?

Not very much. I knew that the five directors went to war, but I am by no means a war buff or a war expert. In fact, the whole reason I went toward this was because it was one part of film history that I felt I had not only not explored, but had kind of actively dodged.

The one thing I looked into in advance was to make sure that all five of them had extensive archives, because I thought that would be the only way I could do this. But I approached it the way I think a lot of movie fans might approach this, which is ‘What is this IMDB gap, and why is it there?”

When you talk about archives, you mean personal archives?

Yes, all five of the directors have their papers in different places.

Are they held by families or universities?

Three of them are held by the Academy Library. Ford’s papers are in Indiana, and Capra’s are at Wesleyan. I did know sketchy stuff. I knew that Ford was at the battle of Midway, that Stevens had been one of the first at the camps, and that Capra had done the “Why We Fight” movies, although I had never seen the “Why We Fight” movies.

I saw the “Why We Fight” movies on public television years and years ago. I was fascinated by this idea of commercial cinema being used to educate and indoctrinate the public. I was aware that it happened because I was a film student. But I didn’t realize that the Capra series was so direct in its methods until I saw the films. They really do speak directly to the viewer, very plainly.

Although one interesting thing that I didn’t realize until I got into the book was that the “Why We Fight” movies, which I had always thought were made for the public, weren’t. They were actually training films. That actually became a point of distress for Capra, because while all of his colleagues/competitors were at least making war movies that were being avidly consumed by the general public, he felt that his audience was unfairly restricted.

And so he spent a lot of time getting his favorite of the “Why We Fight” movies seen publicly. And he succeeded with three of them. But the American public didn’t care. The films weren’t successes with the public.

Can you tell me a little bit more about the relationship between the United States government and the filmmakers who were collaborating in the propaganda effort? I was struck by the fact that, in most cases, it was one highly placed bureaucrat who seemed worried about ethical issues, such as whether it was OK to futz around with chronology in documentaries, and whether it was permissible to include re-creations, and whether the demonization of the Japanese was in danger of crossing the line into outright bigotry. But it seemed like the attitude of the directors was “whatever works, I’m for it.”

I’m not sure that they all had a “whatever works”

attitude. Capra did: He basically came into the job saying “Just tell me what I’m supposed to do.” He was actually looking forward to following orders. Others, like Ford, had a more adversarial relationship with authority from the beginning—something that all of them, even Capra, eventually developed.

I think, partly, the relationship was defined by the experience the filmmakers had working for studio heads—their knowledge that to get anything done well, you had to fight the interference of higher-ups who wanted to make it worse. That was certainly Huston’s attitude, and also Stevens’s–he often complained that men in Washington were making decisions about what should be done without any knowledge of life in the field. Which is something people still complain about

today.

The bigotry question is more complicated. Wyler, for instance, was so sensitive to the plight of black soldiers in the South that he essentially walked away from making a documentary about them because he was certain that the Army wanted it to be sugar-coated—which it did. And the subject of how to depict the Japanese didn’t only pit filmmakers against the Army, but different government factions against each other. By the time they could reach any kind of agreement about

that, the war was literally already over.

Of these five guys, is there any way to determine how invested they were in the war itself? One of the things I find intriguing about this book is the sense of all of them all getting swept up, in a way. It’s hard for me to tell how ideologically driven any of these guys actually were.

I think the answer is different for each of the guys. For Wyler, who was the only Jew among the five guys that I write about, the war was obviously very personal. He had relatives in Europe whom he’d been trying to get out for years. For Huston, for instance, I’m not sure how personal the war was. I think he at least going in saw it as an adventure, a chance to test his mettle.

Which seemed to be the way he treated a lot of film shoots!

Right. That kind of imagery we have of Huston as this deep-voiced swashbuckling gadabout was an image that he himself really enjoyed cultivating. For Ford, they were all invested in the outcome of the war, but for Ford a lot of it was about not having been in World War I, which he was old enough to have been eligible to serve in.

So he’s retroactively making up for lost time?

I think so. Or, if not making up for lost time, I think Ford had questions about his own courage that had lingered for decades, since the end of the First World War. I think he was fascinated by questions of courage, and also, once he was in the war, [that he was] really moved by seeing how brave younger men were, and how unhesitant they were about putting themselves in harm’s way.

It’s fascinating to see how, in making these films that have propaganda functions, these directors were still making William Wyler films, John Ford films, John Huston films. This is particularly striking in the case of Ford’s war documentaries. I’d seen “The Battle of Midway” years and years ago, so I’d forgotten that he works “Red River Valley” into the score. It’s such a John Ford touch that you could almost picture viewers even back then going, “Really?”

Not only “Red River Valley.” The movie has four narrators in 18 minutes, or two narrators and two audience surrogate voices that you hear on the soundtrack. Two of them are actors from “The Grapes of Wrath” and two of them are actors from “How Green Was My Valley”: Henry Fonda and Jane Darwell, you hear them on the soundtrack, and it’s kind of like they are an older woman and a young man sitting in the audience, commenting on what they are seeing in the movie as it is unfolding.

And then the movie ends with the burial of our heroic dead, and the last shot is of Major Roosevelt, the son of the sitting president, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Was the president’s son even present at the scene? Or is that an editing trick?

Yes, he’s at the burial. Or…maybe not. It’s really unclear. When you see the movie, there’s tis really glued-in looking shot, and it’s from a different angle. There’s a burial and you see lots of people reacting to it. And the light looks different, the angle looks different. Ford never said anything about it.

But Ford and Capra especially were really conscious of having to work the system to get what they wanted. And they had ample experience of that [from] working in Hollywood. Capra said openly during the war that he thought that was training for working with the War Department. He said that what he learned was never give in to them about anything.

And then you have this anecdote about John Ford basically stealing footage from one of his own projects, and then he goes and cuts it at some little place far away from the Hollywood machinery, where it’s inconvenient for anybody to try to stop by and interfere with him!

There was this fear that their best stuff would be poached for newsreels. These guys weren’t making newsreels. And so there was this constant tension between the War Department, which wanted the best footage to get out early and was willing to strip-mine these directors’ work for the good stuff, and the directors, who wanted to be left alone to make actual movies.

There was an effort after 9/11 to create something very similar to the phenomenon that you’re describing in the book. The Bush administration was going to recruit the best minds in Hollywood to make propaganda to fight this new world war after the terrorist attacks. That never really happened, not in the way they hoped it would happen, and I’m wondering if you had any thoughts as to why?

I’ve thought about it, of course, and I wish that I had a great answer. I think one thing that I became much more conscious of while I was writing this book and while I was researching it was that the portals of information for ordinary people were very narrow. If you wanted to hear about the war, you listened to radio. If you wanted to read about the war you had newspapers and a limited number of magazines. If you wanted to see the war you had to go to a movie theater. When we hear that nostalgic thing about how 80 million people a week used to go to the movies back then, I think it is important to remember that they were going to the movies for news. That was a way of seeing a weekly newscast. So now, we get our information so quickly and from so many sources that even the best minds in Hollywood couldn’t cerate something that would be as guaranteed to stream into the collective consciousness as thoroughly as it was possible to do during World War II.

If 9/11 had happened five or six years later, maybe they would have recruited a bunch of directors to make YouTube videos, or something like that?

But even if they had done that, who knows how many people would have watched them, or how those videos would have distinguished themselves from the noise that is in all of our heads all day?

And it was more one-way during World War II. There were no channels for talking back to the propaganda.

There were none. There were letters to the editor, and that was it.

What do you think of the argument that it’s the ability to critique and pick apart things makes it impossible to ever again mount an effort like the U.S. government’s cooperation with filmmakers to produce World War II propaganda? That you need the kind of unanimity, that kind of groupthink, that existed back then?

I’m not sure that’s necessarily true, because to the extent that there was unanimity, it was only created by Pearl Harbor. Before that, the country was divided. It wasn’t just the lunatic fringe that was saying ‘this isn’t our war, this isn’t our problem, let’s keep out of it’. It was a substantial number of people.

And once we were in the war, there was unanimity that we should win, but there wasn’t necessarily unanimity about a lot of other things. As the war goes on, especially in 1943, when the Presidential campaign starts kicking in, there were Republicans who were absolutely open in the House and the Senate in saying that the war was being protracted as a way for Roosevelt to create a kind of unofficial lifetime Presidency for himself.

I think if we had had the Internet that noise would have been amplified, but there was plenty to fight about during the war. People did fight about it.

Returning to the individual directors, you’ve really created a set of character sketches of these five filmmakers. It’s fascinating to see their psychology come into play as they’re creating these movies. Capra really stood out the most for me, because although I have read biographies of Capra, I had forgotten what a self-aggrandizing blowhard he could be, and what a mess his politics were.

It’s true.

But he does go on to make “It's a Wonderful Life” which is a very humbled-by-war sort of story.

In some ways, although for him “It’s a Wonderful Life” is also a direct expression of his ego. In some ways it is about his fear that Hollywood had forgotten him and had gone on without him.

One thing that I think is interesting about “It’s a Wonderful Life” is that it’s the first movie he made when he was back from the war, and the last movie of note that he made, period. It was over after “It’s a Wonderful Life.” And it’s the movie that he had the greatest hand in writing. I think it’s the only one that he successfully got a script credit for. It came at a time in his life when he had come back to Hollywood and had really expected that the tickertape parades for him would never end.

And it was with some justification, because Wyler after the war said that he thought the “Why We Fight” movies would be Capra’s most enduring legacy… that they were the most important movies made during the war. So that’s an indication of the esteem in which he was held at that moment.

But then he comes back to a Hollywood that has gone on without him as it went on without everyone. And new stars have been created, and new directors have risen. It’s not like he wasn’t wanted. But just the fear that Hollywood could do without him connects to a big change that he made in “It’s a Wonderful Life”. In an early version, it was supposed to be not “What if Jimmy Stewart had never existed?” but “What if Jimmy Stewart had been a bad guy?” That was the alternate narrative. Capra changed it to ‘had never existed’ because I think that tapped into his deepest fear.

And yes, his politics were a huge mess. He was incredibly reactive to whatever the last thing was that had been convincingly yelled at him. Or whatever the last thing was that he had been accused of.

And so in a way the war was perfect for him, because the propaganda movies that he was making during the war were a really simple and clean reality. He came up with, much more than the government, the message of the “Why We Fight” movies, which was that we fight for freedom, they are fighting for slave world. We believe in tolerance, they don’t. We believe in democracy, they don’t. He shaped this message. He didn’t have to get into things like “How do you feel about labor unions?”

And it seems like there were instances where he could have gotten into those issues but chose not to.

His ego was invested during the war in being able to get these movies made, but he was actually not a prima donna about anything but that. He really wanted to serve. The only thing he got brash or egotistical about was when he thought either people were preventing him from making the movies or preventing the movies from getting seen.

But his politics were always really really strange. Katharine Hepburn said that “happy to be here” was the depth and extent of his political commitment.

Huston’s a fascinating character too in that he’s capable of making something of the depth of “Let There Be Light” but then he goes on to make commercial movies that, while not without a certain depth, are not penetrated by harsh reality, at least not in a way that his war experience suggests that they should have been. I guess what I am getting at is that, the war changed these guys, but how much did it really change them as artists?

The answer is different for each guy. For Capra, you could say that it ended his life as an artist. After “It’s a Wonderful Life”, which was not a success when it opened, he could not get his swing back. For George Stevens, it absolutely changed him. He was so lastingly traumatized by what he saw at Dachau, he said, that he never made a comedy again.

To me, with Huston, the place you see the war in his later movies is a kind of skepticism about power. Huston made three documentaries during the war, and in all three cases, in a kind of escalating way, he had trouble getting them shown, to the point where, as you know, “Let There Be Light” was banned for 35 years. And I think he really, if you look at the cynicism, not only of the movies he made but also of the parts that he was attracted to… I think of him as Noah Cross and the patriarch in “Winter Kills.”

I was going to say! What a horrible person that character is. He’s like Papa Joe Kennedy crossed with the devil.

And Huston was definitely a mixed bag as a person, definitely a very difficult man. But I think four of the five of them knew that the war had changed the country, and would change the way they made movies. And it did change the way they made movies.

And the only one who really imagined that the war was a kind of horrible interruption after which things would go back to the way they were before the war was Capra. And that’s why, I think, “It’s a Wonderful Life” is so infused with nostalgia. It’s this kind of desperate lunge to say ‘can we all just pretend this never happened and go back to the way we were’.

It seems as though Ford might have been deepened the most as an artist.

His Midway experience was really profoundly…I mean, to film those young men and then to watch them all die, I think shook him very deeply. He’s complicated, because alcoholism is a big part of his story, although that word was not used very much during the time that I am writing about. He’s such an enigma as a person, incredibly sensitive but also incredibly nasty, capable of beautiful film art and real cruelty. He’s a difficult guy to understand.

I had to make the decision fairly early in working on this that I was not going to end the book with some big exigesis about reading the war into their later movies, because I felt like it would be a strange pivot from doing a firm piece of narrative that runs from 1938 to 1946 and then ends, into a last act of criticism in which I was like, “And here is how ‘The Searchers’ is actually a World War II movie.”

I just really felt like, by the end of the book, I’ve hopefully laid enough groundwork for people who are interested in those movies to go look at the movies, maybe, through “war eyes.” But I wanted to stop telling my story when my story stopped.

Where did you get some of the more obscure little details?

The archives were great. The archives had letters, they had diaries, they had datebooks in some cases, they had drafts. Sometimes they had typed drafts, with handwritten redrafts over them.

It’s amazing how personal the stuff that gets thrown in those boxes for 70 years can be. When I was looking at the Huston archives, at one point I found a script for a Capra film that he had been assigned to work on called “Know Your Enemy: Japan.”

You write about that, too.

Yeah, and I was paging through it, and on the blank back of one of the pages was this love note that some woman [Huston] was sleeping with had scrawled to him—the script was obviously [lying] on a night table or something—saying something like, “I crawled through your window at 3 a.m. to see if you were here and you weren’t. Who were you out with? I stole all your cigarettes.”

So that made me look at every page because you never know what you’re going to find. There are a lot of great details to be dug out of those archives.

And also, on the other side of it, the government side, I spent a lot of time at the National Archives in Maryland and the Library of Congress to sort of fill in the army side and the Office of War information and the War Department material as much as I could, because some of that material didn’t end up in the directors’ archives.

So what do you do? Do you just go into an archive and say, “Hey I’m writing a book. Can you pull out the boxes of John Huston stuff?” Or is it more complicated than that?

In most cases, it’s not more complicated than that. A lot of them have these things called finding aids, which are … I mean, the big question with any archive is how scrupulously has the material been catalogued? Is it just boxes of unorganized, undated stuff, which is kind of a nightmare? Or, as was the case with many of these archives, has someone done boxes of correspondence, boxes of scripts? Have they organized it by date? Have they indexed it well? Fortunately, the places I was going had fantastically well-organized archives, so that just saves you days, if not weeks.

And then you’re just sitting there at a table or on the floor, just reading stuff?

Yes, at a table. Sometimes they make you wear gloves if it’s really fragile onion-skin paper or something. Because you’re looking at something that’s 80 years old. Yes, you’re reading and typing notes into your laptop and trying to absorb as much as you possibly can.

And you really never know what you’re going to find or how deep the material’s going to be. I just get into this headspace where it’s like, I type everything I see. Because you don’t know what you’re going to want. The archives were absolutely crucial, but also I used a lot of secondary sources. Tons of people wrote memoirs. There were some really useful archives of guys who weren’t in my five, but who knew them. For instance, there’s this guy Eric Knight, who was a Capra associate who rewrote a lot of the “Why We Fight” series. His papers are archived.

So I just dig and dig and dig until I’m satisfied. My big fear in doing a book like this is that it gets finished and gets published and then somebody says “I don’t understand why you didn’t go look at this huge collection.” So I try to satisfy myself that I’ve found everything there is to find.

Are there practical things that you’ve learned about researching and writing a book like this?

About researching it? Go find everything.

And putting it together: It was really important to me that this be one pretty chronological narrative, because it was five guys. I didn’t want to do a section on each of the five guys where I take you up to D-Day five times an you’re sort of “Groundhog Day” style reliving the war through each director. Because also I really loved the fact that they interacted and crossed paths. There’s a time where Wyler and Ford are in the same place, and Ford’s treating Wyler terribly.

And there’s a scene where Frank Capra hires George Stevens.

Right. And then Capra and Wyler and Stevens go into business together after the war. So it’s like five guys, but it’s one story, and I wanted to tell it as chronologically as possible because, as with the first book, I felt like if I was asking people to alternate among five stories, I at least wanted them to feel well oriented in time. Alternating between five people and jumping back and forth in time feels like too much to ask of a reader. So I am a huge outliner and huge reviser of outlines. With this book I had five columns, one for each director: timelines of when everything happened. And then I had a sixth column about interesting stuff that was happening in the movie industry at that moment. And then I had a seventh column about what was happening in the war. I found all kinds of interesting stuff that became important in the writing of the book, just by looking across those columns and saying. “Oh, when Capra was doing this, that’s why Wyler wasn’t around, because he was doing this.”

Or a director gets a cockamamie idea for one of their movies, and you realize that a certain congressional initiative was announced a day earlier, and you wonder if that’s why they came up with that idea—if that was the spark.

Right. Exactly. You start to feel so immersed in a particular moment.

I have to answer really basic questions for myself that are probably second nature to war experts. For instance, was there a stretch when we thought we were losing? When did the cultural attention start turning from the war in the pacific and the Japanese to the war in Europe? Did it turn to the war in Europe? Where does North Africa come in?

And in answering that basic kind of stuff, I was often able to simulate for myself what their thinking might have been at that moment.

It’s also fascinating to me how you delve into the history week by week and month by month by telling the story of these five guys. It drove home for me the fact that from 1939 to 1945 was not that long of a time.

Right, and our war was the beginning of ’42 to the middle of ’45. It’s three-and-a-half years that’s just world-changing.

You get the sense of things happening with incredible speed. There’s that part of the book where there’s congressional hearings that are about isolationism and the fear the movies are influencing people to want to enter the war. And then suddenly, while these hearings are happening, sentiment shifts, and the pervading question becomes ‘Why are you trying to keep us out of the war?’

Exactly. That was momentous, but there are things that are more mundane about the movie industry like in 1942 and 1943 the studios could not get enough of war content. During those years they released an average of three movies a week with some war content. Some of them were musicals or service comedies or spy movies or Sherlock Holmes updated to a World War II context, but three movies a week.

And then, suddenly at the end of ’43, the bottom falls out for those kinds of movies, and there’s this kind of fascinating moment where Hollywood starts to separate itself from Washington and its interests and say, ‘Yeah we know you want us to make these movies about war with these positive messages, but our audiences are sick of them and so we’re not going to do it.’

And so the character of movies changes, and it changes really fast, because back then you could really pivot quickly. If you make a decision that “We’re not going to make any more of these movies” in January, by May the content of what people were seeing was going to be different.

You paint a portrait of an industry that’s much more nimble than the one that we’ve got now.

It was really nimble.

I was amazed to read in your book that filmmakers and the studios could continue to revise a movie up to six weeks before it came out. They could shoot new endings on the fly.

And they did all the time. I would say it is more like television. We should also remember that these people would have either laughed or recoiled in horror at the idea that you and I are sitting at a table in 2014 talking about what John Huston did in “Across the Pacific”. They thought that a lot of what they were doing was completely disposable. Nobody thought that these movies they shot in six weeks were for the ages and would be looked at as documents of the time 70 years later. But also it was very freeing. They turned them out and then went on to the next one. If one of them went badly, their attitude was more like a show runner who now would say ‘oh yeah, episodes 14 through 17 this season were just not very good.’ They were just more casual about it.

You also paint a picture of a movie-going culture that is unimaginably different from what we have now. It got me realizing that the 1950s-1960s post-television sense of cinema is not the sense of cinema that people collectively always had. Basically, the cinema that you portray in this book is like television on a huge screen, a screen that they’re all watching in a giant community living room with 500 to 1,000 seats. This is where they all go to watch their version of television. They come in and buy their ticket, and sometimes they come in in the middle of a feature and just stay and cycle through it to catch the beginning of it.

Mostly. Starting times were very rarely advertised. We all have had relatives of that generation and we’ve all heard the stories of ‘Oh, for a dime you would get two cartoons and a newsreel and a double feature.’ And it’s true, but one of the things they never talk about is how seamless it was. You would walk in in the middle of a feature, stay to the end, there weren’t breaks, and the cartoons would start again.

There was this kind of flow between information and entertainment. You’d see feature films that were infused with propaganda or political messages, then newsreels that were infused with entertainment value and music. And you might see John Ford’s “The Battle of Midway,” which has music from Ford movies, and actors from Ford movies.

And the voice of Henry Fonda chiming in suddenly to narrate!

Right. I can only guess at that, because it’s such a hard thing for us to imagine, that kind of genre blur. You just went to the movies, but it wasn’t quite as categorized. You were going to see news, you were going to escape from news, you were going to be entertained, you were going to learn something.

You were going to see Mickey Mouse hit Goofy on the head with a mallet…

Right, and at some point, a ten-minute classical music short with Toscanini conducting. There was a lot of that stuff.

It’s a vanished world.

A really vanished world, and a vanished culture. Everybody would go to the movies, sometimes twice a week. And by the way, they would advertise newsreels outside the theaters as coming attractions, just as much as they did with features.

A recurring theme in this book is how fast history moves in comparison with art that’s inspired by history or responding to history. How much of the delay in getting certain war documentaries to the screen do you think was due to artistic perfectionism, and how much was just a matter of logistics?

I don’t think it was artistic perfectionism. John Huston, for instance, managed to finish “Report from the Aleutians” and get it the way he wanted it pretty quickly, and then went mad with frustration while the government sat on it, and Ford also turned “The Battle of Midway” around with great speed. Wyler was slow about finishing “The Memphis Belle,” but that was very much in line with his personality and his perfectionism before the war. And although a lot of Capra’s very ambitious plans for war filmmaking—the “Know Your Enemy” and “Know Your Ally” series, for instance—were delayed over and over again, the issue there was less perfectionism than it was sheer bewilderment about what exactly should go in those movies.

Which was understandable since the War Department itself was often maddeningly vague about what message it wanted the movies to send.

Of all the documentaries and training films you saw while writing this book, what’s the one that you find yourself thinking about the most?

I spent a couple of days in the Motion Picture Reading Room at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., sitting at a study carrel watching all of the reels of George Stevens’s footage, including the Dachau material. There’s a lot of it, and although I considered myself to be pretty inured to images of death-camp atrocity and horror, I don’t think I’d ever watched footage like this before from the perspective of thinking about who was holding the camera and how that act would resonate for him for the rest of his life. So I find myself really still gripped and haunted by that.

Can you describe the difference between watching, say, “The Best Years of Our Lives“, or “It’s a Wonderful Life” or “They Were Expendable” before researching the book, versus watching them during or after?

I think any journalist who covers movies or television with passion has had the experience of falling a little bit in love with something the more you know about everything that went into it. After having lived for the last four-plus years with the wartime experiences of these guys, I can’t pretend to be coolheaded or objective about “Best Years” or “They Were Expendable”. They’re very personal to me.

But maybe coolheadedness and objectivity actually isn’t the best way to approach these movies. It’s certainly not the way they were approached by their directors—the movies are wrenched right out of their hearts, not just their minds. And I love the feeling of understanding that a little better. And also of seeing something new every time I look at those movies, which I still feel, and expect to continue to feel, for a long time.