When filmmaker Harun Farocki died last week at 70, critics and artists mourned him. Among them was Houston-based critic Michael Sicinski, who writes about movies for CinemaScope and Cineaste and on his website The Academic Hack. He said on Twitter that he’d studied only briefly with Farocki but that the experience had a profound effect on him. I asked him if he wanted to elaborate on that statement, and perhaps explain his importance to people unfamiliar with his work; the result was this extraordinary email, which I’m publishing in its entirety here.—Matt Zoller Seitz

Although it is factually accurate to call Farocki a “German

documentary filmmaker,” all three of the words in that phrase seem somehow

inadequate. Calling Farocki “German” is probably the most unproblematic

of the three designations, as he spent much of his career based in Berlin,

identified quite deeply with German film culture, and eventually became

something of an axiom within it.

Farocki was born in January of 1944 in

Nazi-occupied Sudetenland, the present-day Czech Republic. His mother was

German, his father an Indian-German. After the end of World War II, Farocki’s

family lived in India and Indonesia, but he returned to Germany and, at age 22,

entered the Deutsche Film- und Fernsehakademie Berlin (dffb), a school now

particularly well known as the wellspring of the “Berlin School” of

contemporary German cinema.

Although Farocki’s training and aesthetic interests were

deeply bound with German history – the New German Cinema’s commitment to

excavating and exorcizing the Nazi past, as well as retrieving the humanistic

values of Weimar cinema – his political interests inevitably made him as much a

global filmmaker as a specifically German one. This can be seen in films such

as 1992’s Videograms of a Revolution

(made with Andrei Ujica), one of Farocki’s better-known works. It is a critical

examination of the Romanian revolution, made using real-time television footage

from the Ceausescu regime intercut with analytical commentary. (The likely

influence of this film on the fine work of Corneliu Porumboiu is certainly

worth considering.)

Some of Farocki’s later efforts also move well beyond

Germany’s borders. His 2000 work I

Thought I Was Seeing Convicts (which exists both as a single-channel tape

and as a video installation) exposes the California correctional system’s

underlying practices by patiently working with surveillance footage from the

state pen in Corcoran. And In Comparison (2009),

one of Farocki’s last films to receive wide exposure in the U.S., is a

meticulously assembled observational documentary about, of all things, brick

production around the world. Using his carefully articulated mode of montage,

Farocki created visible dialectical relationships among the material practices

of production in France, Germany, India, and Burkina Faso. In a remarkably deft

homology worthy of the Russian Formalists, Farocki created In Comparison as a story of bricks whose piece-by-piece

construction directly mirrored its subject matter.

At the same time, of course, Farocki never failed to bring

his cultural critique right back home to Germany. Like New German Cinema

fellow-travelers Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet (with whom Farocki

worked on their Kafka adaptation Class

Relations), Farocki considered the repression and capitalist

acquisitiveness of postwar West Germany to be a form of cultural amnesia, a way

to both sublimate Nazi guilt and to divert all that well-honed discipline into

more acceptable channels. Farocki’s efforts along these lines were sometimes

highly focused, as in An Image (1983),

which displayed the tedious production process behind a Playboy centerfold, or the later Still Life (1997), which expanded on John Berger’s thesis regarding

the connections between Renaissance still life paintings and contemporary

advertising photography by providing deep analysis of the former, and again

showing us how exactingly the latter is constructed.

Farocki was a deeply materialist filmmaker who saw the editing

process as a site for the physical construction of argument. This meant that,

ultimately, a film could and should connect Germany with the world, and also

the documentary form with other modes of address. When I indicated above that

calling Farocki’s work “documentary” is partly inadequate, it is because the

artist so often relied on speculative fiction, re-enactment, or the analytical

conjecture constitutive of the essay form, all in the service of achieving

truthful arguments. The two films that remain Farocki’s finest achievements

exemplify this willingness to move outside the confines of simple reportage.

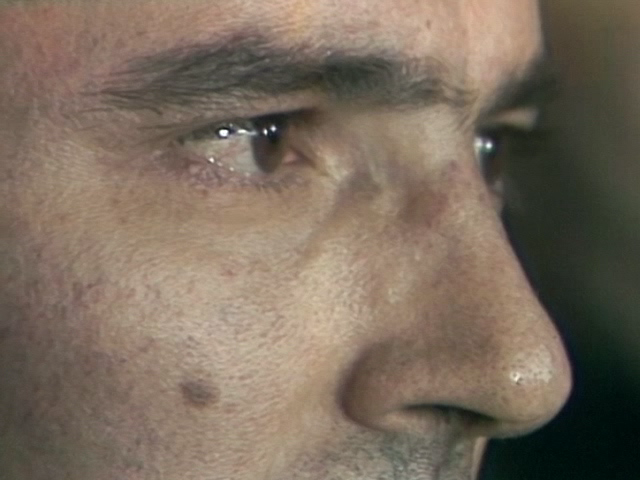

1969’s Inextinguishable

Fire is one of several early films Farocki made in protest of the Vietnam

War. In this case he is specifically addressing the use of napalm, and directly

condemning Dow Chemical Corporation for manufacturing it. Working in a

Brechtian theatrical mode, Farocki sits at a table as a kind of narrator /

host, discussing the effects of napalm. The filmmaker rolls up his sleeve and snubs

out a cigarette on his own arm, then notes that napalm burns seven times

hotter. The majority of the film features intentionally stiff performers at a

makeshift Dow Chemical plant, trying to reckon with their role in manufacturing

hot liquid death.

1989’s Images of the

World and the Inscription of War is a very different film, one that

contains no performance segments but is sprawling in its essayistic reach.

Containing scenes of robotic architectural etching, fluid wave analysis,

photographs from Auschwitz, and theories of perspective from the Renaissance

onward, Images is Farocki’s grand

statement on human culpability with respect to knowledge and ignorance. There

is no neutrality in how we perceive the visual world, the film argues. The key

fact around which Farocki organizes his other related ideas is the discovery

that Allied reconnaissance pilots photographed Auschwitz during World War II

and were in position to destroy it. However, the pilots didn’t know what it

was, were not looking for it, and so the images were misinterpreted, costing

thousands of Jewish lives.

As is certainly clear, Farocki was a deeply intellectual

artist, and the impact he has had on film culture has been a decidedly critical

one, based in a belief that images are constructions to be interrogated both in

art and in life. When I claimed, finally, that “filmmaker” was yet another

inadequate appellation for the man, it was because his total practice

encompassed so many more vital elements, some of which may even prove to be

more influential than his films. Lately Farocki had been showing more video

installation work in galleries, sidestepping the problematic selection

processes of film festivals.

But Farocki also had a significant career as a writer,

editor and theorist. From 1974 to 1984 he edited the highly influential German

magazine Filmkritik, a publication

that focused less on reviews and evaluation than on formal analysis,

explicating how important films performed their rhetorical work. Some of

Farocki’s major essays from this period are collected in the book Nachdruck / Imprint, available in a

German / English bilingual edition.

The spirit of the Filmkritik

project – analysis over “criticism” can be seen today in the German film

magazine Revolver, edited by

Christoph Hochhäusler and Benjamin Heisenberg, younger filmmakers associated

with the Berlin School. And, of course, one cannot mention the Berliners

without noting that Christian Petzold, one of the members of the first

generation and the director who has become something of the group’s

international standard-bearer, had a long association with Farocki. Beginning

with Petzold’s breakthrough film The

State I Am In (2000), Farocki was the co-writer on Petzold’s films Ghosts (2005) and the recent Barbara (2012).

And Farocki was a teacher. He recently held a post at the

Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna, and taught at Berkeley for several years in the

90s. I was fortunate enough to be at Berkeley back then, and I was able to take

a class with Harun. The course was co-taught with Kaja Silverman; the two of

them were also working on their excellent, underrated book Speaking About Godard at the time. The premise of the course was

theory and production, considering the relationship between the still and the

moving image. I was utterly hopeless behind the camera, and luckily the lousy

video I made has been lost to the winds of time.

But Harun’s pedagogy – direct, occasionally gruff, but

unfailingly supportive and based in a rare, active listening – had a real

impact on me. In one of the best lessons of the course, Harun loaded his 16mm print

of Images of the World onto the

school’s Steenbeck flatbed so we could discuss his editing decisions one by

one, for nearly three hours. This simple gesture helped to open a world of

possibility for me, just to think of “cinema” as material stuff that was arranged, could be rearranged, and therefore

different. As I’ve continued watching Harun’s films over the years, new lessons

were unfailingly revealed.