Last night I had a dream about “Deadwood.”

It was 2017, and David Milch’s western had miraculously returned to HBO, eleven years after its unexpected cancellation. The opening credits were essentially unchanged, but they were missing a few familiar names and had gained a few new ones. And the first shot was a close-up of a smoldering pile of rubble.

The viewer realized with a shock that we had skipped ahead in the timeline. The plan, as outlined by Milch, was for the town of Deadwood to burn down at the end of season four—an event that occurred in reality on September 26, 1879—and then be rebuilt in increments through season five. The show’s cancellation interrupted that narrative and created a serious production and logistical problem, nearly as pernicious as the challenge of reassembling what was, at the time, the largest cast of regulars in scripted TV—a veritable murderer’s row of character actors who were thenceforth cast into the pop culture wilderness in search of fresh employment.

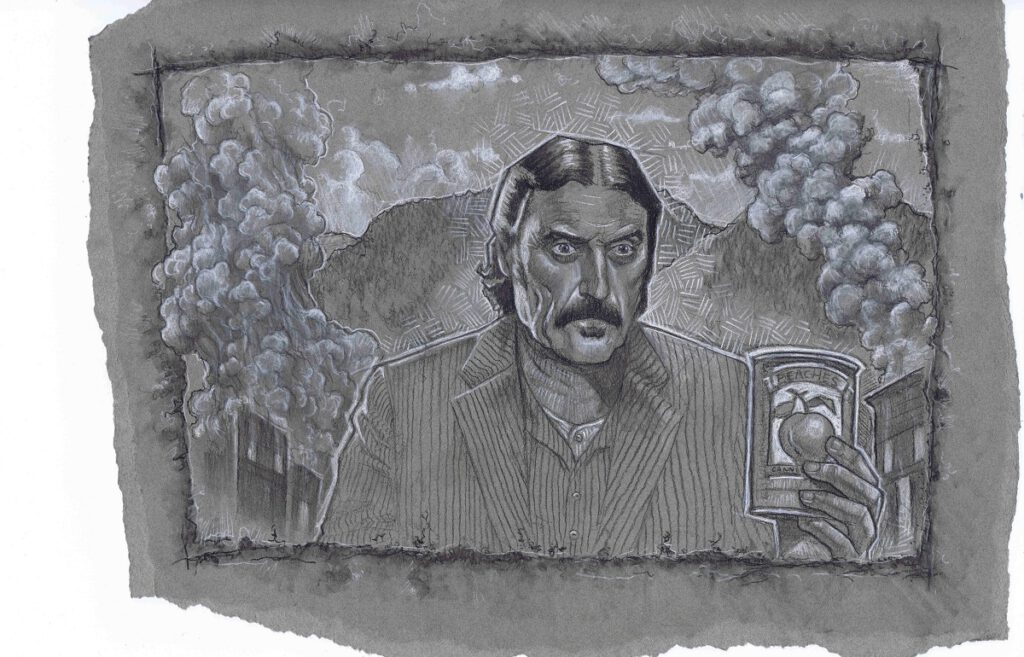

After a long moment, a sooty boot kicked the pile and broke it apart. The boot kept kicking it and kicking it until we saw a glint of dingy metal. Then a sooty hand reached into the frame and lifted a piece of a charred ceiling strut, revealing a can of peaches.

The hand belonged to Al Swearengen, the owner of the Gem Saloon. The camera pulled back to reveal Swearengen contemplating the peach can as if it were Yorick’s skull. His face was partly masked by black and grey sweat-streaked ash, and his dark suit was shot through with moth-holes burned by cinders.

He unsheathed his throat-slitting buck knife, forced up the can’s lid, speared a peach-half and lifted it, syrup gleaming on the blade, and popped it all into his mouth at once as if it were a piece of hard candy, and chewed.

After a long moment, he raised an eyebrow approvingly, took a long look around, and said, “If you want to hear God laugh, tell him your plans.”

The camera pulled back again, taking in Swearengen from head to toe, and in the process revealed E.B. Farnum, the town’s erstwhile mayor, standing nearby, clothed as much in soot as finery, chastising his dimwitted sidekick Richardson, who puttered about moaning and clutching at his temples. The camera pulled back further and rose higher and higher, taking in a panorama of destruction where a nascent hub of civilization once had stood. Everything was in ruins: the Gem Saloon, Cy Tolliver’s upscale Bella Union, Mr. Wu’s Chinatown with its caged women and chickens and flesh-eating hogs, Farnum’s Grand Central Hotel, the jailhouse and sheriff’s office where Seth Bullock had once jailed thieves and drunks and disturbers of the peace, the schoolhouse where his wife Martha had taught the town’s children, the newspaper office where A.W. Merrick had chronicled the town’s mostly-idealized history, the cramped cabin where Doc Cochran had treated the sick and elderly and deranged: it was gone, all gone. The black hills of South Dakota seemed to have acquired a brood of children. Three hundred buildings had been razed into heaps of blackened toothpicks.

At the farthest edge of the background you could faintly discern the hunched-over figure of Calamity Jane rummaging through a molehill in search of something to drink.

After that, it’s all a blur—sort of a mind-trailer consisting of intimations and images, all mixed, strangely, with stories on a computer screen and on newspaper and magazine pages (like an old-fashioned movie montage) revealing how Deadwood had returned for a fourth season and gotten around the problem of having to rebuild one of the largest and most complex sets in the history of moving pictures—an actual working town consisting of historically accurate building exteriors that all housed miniature soundstages, the better to frame shots that juxtaposed people plotting or drinking or screwing in the foreground against pedestrians and horses and carriages roving the town’s muddy main thoroughfare at middle-distance and more people in the buildings on the other side of the street, glimpsed through door frames and windows.

The masterstroke, it seems, was to skip ahead on the timeline, so that season four became an ellipsis in the master narrative. This choice absolved HBO of the expense of recreating the town so that it exactly matched what we’d seen in the first three seasons.

Apparently, after heated discussion and some consternation, the decision had been made to give continuity permission to go to hell.

This not only saved HBO and Milch’s crew tens of millions of dollars and untold man-hours of preparation and construction time, it also introduced an element of mystery into the story of Deadwood: what person or persons or institution was responsible for the conflagration? How did this catastrophe come about, and what could be done to keep it from happening again? Every character blamed some other character, or some failing in the town’s government, or within individual institutions: the sheriff’s office, the recently established fire department, the godless heathens, the ignorant cattle-herders and stagecoach drivers who’d been repeatedly cautioned to dispose of their cigars and cigarettes with care, and those Yankton politicians who had been stingy about dispersing funds that would have brought water down from the rivered hills by way of above-ground wooden aqueducts.

In time, it became clear that what we were seeing in season five was actually a combination of season five and season four. Season four’s narrative was about how a nexus of greed and incompetence and generalized ignorance about collective responsibility had sparked the fire that burned Deadwood to the ground. This narrative was encoded within the dialogue and monologues of season five, which concerned the rebuilding of the town and the re-imagining of its community.

In this dream, we saw businesses founded, friendships established and re-established, resentments rekindled, grudges set aside, love affairs nurtured. There was a marriage and a birth, an adoption and several deaths, some unspeakably savage, others unremarkable. And all of these stories unfolded against an aural backdrop of hammering and sawing, and a visual background of cross-timber grids rising up to form walls and roofs. Over the course of thirteen episodes the show got visibly darker, but in a way that ironically lightened the mood, because the comparative lessening of sunlight was the byproduct of all those new buildings going up.

Thus did the narrative of the rebuilding of Deadwood after a catastrophe become the narrative of the re-creation of “Deadwood” after its cancellation.

Nobody complained that all of the actors looked ten years older, because disaster does put the years on.

Near the end of the season, fall leaves appeared on the forested hills in the background, and then winter came, and the characters wrapped themselves in winter coats and scarves and thick gloves. The final episode took place on Christmas Eve. An avalanche poured down on the town, followed by a blizzard. There were no serious injuries and only one death—some yammering drunk from out-of-town that no one much liked anyway—but the deluge of snow cut off many of the citizens from their domiciles. So Al opened his saloon to the dispossessed and brought up crates of peaches and served them along with bourbon and hardtack, and dressed as Father Christmas, and bid his guests, their ranks thick with prospectors and whores and ruddy-faced orphans, and read to them from “A Christmas Carol,” which had been published nearly four decades earlier on the other side of the ocean.

“Scrooge was better than his word,” Swearengen read. “He did it all, and infinitely more; and to Tiny Tim, who did not die, he was a second father. He became a good friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew, or any other good old city, town, or borough, in the good old world. Some people laughed to see this alteration in him, but he let them laugh, and little heeded them; for he was wise enough to know that nothing ever happened on this globe, for good, at which some people did not have their fill of laughter at the outset; and knowing that such as these would be blind anyway, he thought it quite as well that they should wrinkle up their eyes in grins, as have the malady in less attractive forms. His own heart laughed; and that was quite enough to him.”

(Illustration by David Lambert).