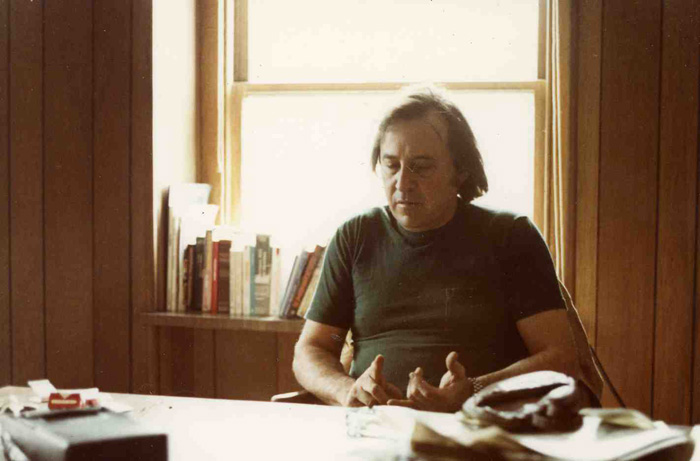

Hollywood, California – “It all comes down to one very simple fact,” Paul Mazursky was explaining. “Betsy and I have been married for 24 years, and during that time almost all of our friends have been divorced. The usual way these things work out is that, after the divorce, you find yourself either seeing more of the woman, or more of the man: It’s hard to stay neutral.

“I don’t know why it was, but in divorce situations we always seemed to see more of the women. One day we had some friends over and one of the divorced women had just bought a house. Something she said suddenly struck me as very strange: On the deed to the house, she said, right after her name, she was described as ‘an unmarried woman.’ As if somehow that described her, or was important to home ownership.”

An unmarried woman. The phrase stuck in the back of Mazursky’s mind and wouldn’t go away. He was dividing his time between New York and Los Angeles, involved in two movies at the same time. His “Harry and Tonto” had just been released, was doing well, and would win Art Carney an Academy Award as the best actor of 1974. And now Mazursky was preparing to shoot “Next Stop, Greenwich Village” on location in the same New York streets he’d haunted as a writer, actor, beatnik and would-be movie director in the 1950s. An unmarried woman…

Mazursky started asking women friends to come over to the apartment for some serious conversations. “I must have interviewed 10 or 15 of our friends,” he remembers. “Of course, as friends, we’d talked a lot about divorce, being single, getting used to being alone, how to cope… Maybe Betsy and I seemed like good people to talk to, because we really do have a wonderful marriage, which is a small miracle. But now I really began to listen to what our friends were saying.”

Those conversations, over a period of a year or so, began to form in his mind as the basis for a movie. Mazursky tended to make a certain kind of film, a mixture of truth and comedy, of laughter growing out of reality, and the subject seemed to lend itself to that approach. He’d dealt with infidelity before, in “Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice” (1970) and “Blume in Love” (1973). But this time it wasn’t sexual infidelity that intrigued him. It was what happened to a woman who thought she was perfectly happily married… in the weeks and months after she suddenly found out she was very wrong.

The conversations turned into notes, the notes turned into an outline, and Mazursky shut himself in a room and wrote the first draft of “An Unmarried Woman.” There were many other drafts – it was an excruciatingly hard film to write at all, and especially to write so that it would be honest and entertaining both at once. But when he was finished, he thought he had something. And Paul Mazursky was right. He had the script for one of the best American movies of recent years.

The problem then was to cast it. The story falls more or less into three acts, held together by the actress who would be at center stage for the entire film. In the movie’s opening scenes, she’s the happily married wife of a Manhattan stockbroker and mother of a 16-year-old daughter. In the middle, after her husband leaves her for another woman, she is what all the words imply – an unmarried woman. At the end, she meets a new man, but the screenplay doesn’t let her off the hook. She’s not permitted to simply fall in love with him and stroll off into the sunset; that would be too easy. No, she has to decide about him, and about herself: What does she really want in a relationship, and what can she realistically hope to give?

It was obviously going to be a very difficult role for any actress. Just as obviously, given Mazursky’s reputation as one of Hollywood’s very best writer-directors, it was going to be a role almost any actress in town would want. “I had a choice,” he was remembering a few weeks ago, drinking coffee in his office at 20th Century-Fox. “I could go with one of the known ladies… a star actress, maybe someone like Jane Fonda. Or I could go with a hunch. The hunch was Jill Clayburgh. I’d had her read for me on two previous films, ‘Blume In Love’ and ‘Greenwich Village.’ She’d read terrifically both times. But both times I wound up casting someone else. And in the work she had done in films… she’d never really come across as well as she’d read for me.

“Some friends saw her on TV, in ‘Hustling,’ based on that Gail Sheehy book. They said she was good. I asked her to come in and read again. She was good. I cast her as my lead. She turned out to be better than I could possibly have expected.”

Mazursky was not exaggerating. I’d seen “An Unmarried Woman” at a screening two nights before, and half an hour into the film I’d become convinced I was watching one of next year’s Academy Award nominees as Best Actress. Jill Clayburgh was that good.

For Mazursky and Miss Clayburgh, “An Unmarried Woman” represents the possibility of important career breakthroughs. Mazursky’s films have usually received good reviews and turned profits at the box office, but he hasn’t had a major financial success since “Bob and Carol and Ted and Alice.” (Even with its Oscar for Art Carney, “Harry and Tonto’s” grosses were good, but not spectacular.)

And Jill Clayburgh has needed a film like “An Unmarried Woman” to bring her career into focus. She fared no better than everyone else involved in the critical and box-office disaster of “Gable and Lombard.” And although she’d been in two comedy hits since then (“Silver Streak” and “Semi-Tough”), it was hard to really appreciate her performances in the midst of the roughhouse and slapstick.

In “An Unmarried Woman,” though, there’s a magical moment right at the beginning that makes everything clear: Alone in bed after her husband and daughter have left the apartment, she hears “Swan Lake” playing on the FM station, and a far-away look appears in her eyes as she fantasizes an announcer: “The ballet world was thrilled last night by the performance of…” And she leaps from the bed and dances around the living room in a T-shirt and panties, and before we’ve quite realized what’s happened, this has become one of our favorite movie characters in a very long time.

We like her for herself, and we like her for the way she relates to the men in her life. Her husband is played by Michael Murphy, an excellent actor who has had the curious misfortune, Mazursky points out, to have come along when conventional WASP good looks are less in demand for male movie stars than some hint of the exotic – some small touch of Hoffman or Nicholson or Pacino.

The man she meets at the end of the film, a British artist, is played by Alan Bates, who liked the screenplay well enough to make this the first movie he has shot in America. (“I can’t exactly take all the credit for that,” Mazursky admits. “The truth is, Alan is afraid to fly across the ocean. At one point, he was considering going by train to Poland to catch a ship to New York. We finally talked him aboard the Concorde, but he didn’t enjoy the flight one bit.”)

With both men, Miss Clayburgh maintains an intriguing mixture of spunk, openness and equality. Her character relates to men, thrives with them, but learns not to depend on them for self-definition. She seems to agree with the film’s woman psychiatrist who argues, sensibly, that men are the problem, yes, but they’re not the enemy.

Audiences at sneak previews seem to love the film. The “word of mouth,” that mysterious quantity that Hollywood regards with so much superstition, has not been better for any film this year. Mazursky sits in his office and drinks his coffee and says: “You know you have a good picture, and then you look in Variety at the box-office grosses, and you just don’t know. A picture has to become an event these days. Look at ‘Smokey and the Bandit’ at $40 million. Who would have believed it? Will ‘An Unmarried Woman’ become an event?”

Who can really say? But if it doesn’t, the people who don’t see it will have missed one.