I came across a photograph the other day of assorted members of the Beat Generation – Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and a few others – and it was like stepping into a time warp. Here were the angriest young men of a generation, the rebels and bohemians of the 1950s who prepared the way for revolutions to follow, and they were all wearing . . . suits and ties. And they had short haircuts. And it was rumored at the time that they stood on tables and read poetry, which may not have been literally true but which certainly inspired would-be Beats in college towns to stand on tables and read, alas, their own poetry. And I thought how curiously one decade is absorbed by the next, things not really seeming to change much from year to year, until suddenly an image from the ’50s strikes you as really being out of the past.

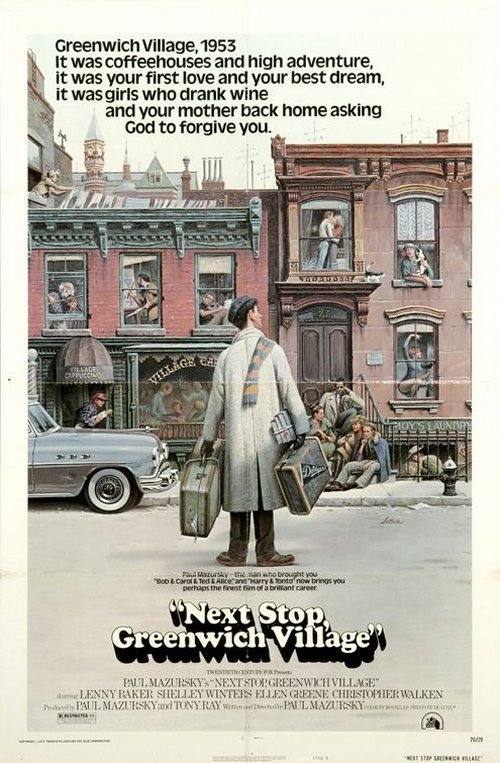

That’s something of the feeling we get, in a good way, from Paul Mazursky’s “Next Stop, Greenwich Village,” which is set in the Village of 1953. That’s not so very long ago, I suppose, and yet period movies from the relatively recent past have a way of looking as dated as costume medieval melodramas. Consider, for example, the hippie beads and headbands of 1968 in “Shampoo.” Or a kind of speech captured forever in “Easy Rider” but now sounding affected and artificial. Or the kids in “Next Stop, Greenwich Village,” who look forward so bravely, so openly, to a future that’s become their past. They’re as hip as they could imagine in 1953. They read poetry and listen to jazz on long-playing records and drink beer at rent parties and have homosexual and black – ah, Negro – friends, and the girls have diaphragms that fail them with distressing regularity.

Mazursky treats the period and its characters with a loving nostalgia and no wonder: This is his story. He’s said that his own life has been the inspiration for most of his films, and that’s most obviously the case in his two autobiographical films: “Alex in Wonderland,” which told of a young, successful director looking for his next film project, and “Greenwich Village,” with its memories of a young would-be actor who left home and went to live in the Village. Mazursky supplies some of his memories to flesh out his hero, the earnest and likable Larry Lapinsky (Lenny Baker). And when the actors audition for roles in a Hollywood juvenile-delinquent movie, we’re reminded that Mazursky left the Village to go West and appear in “Blackboard Jungle.” The movie’s part autobiography and part fiction, but it’s all of a piece because Mazursky captures the tone of the 1950s. Larry and his friends hang around the village, occupy a corner of a coffee shop, live in each other’s apartments, share each other’s problems and answer the regular false alarms of the girl who keeps saying she’s going to kill herself. For Larry, it’s a new world, a challenge; he falls in love with a girl who wants to become a performer, and he actually gets somewhere with her and would have gotten farther if it hadn’t been for the unrelenting raids from the Bronx carried out by his stereotypical Jewish mother (Shelley Winters).

His life at the time seems complete enough, but it’s really a rite of passage, The Village is a way station where it’s possible to try out new ideas and friends, to grow up but also to grow outward. And as Larry finally leaves New York (after a farewell visit to his old neighborhood that recalls scenes in Fellini’s “Amarcord“), we see that he’s leaving more than just the city. Perhaps that’s why the movie seems so fondly dated, because it represents a definite time of life – with a beginning in late adolescence and an end in manhood – that can’t be stretched or preserved, only remembered.