NEW YORK — They said making a movie about Woodstock was like . . . three days without sleep. The cameramen all wired together, with Wadleigh shouting instructions over the earphones. And Don Lenser crying during the Airplane’s set, crying because he was right there on top of them, he practically had his camera shoved down Grace Slick’s neck, he was practically in her mouth, and all that noise pounding through him, surrounded by banks of loudspeakers – big mothers! – and crying, you could hear him crying over the earphones, crying because he wasn’t able to move because he had to hold the goddam camera steady…

Wow…said softly. Wow. They were flying in vitamin B-12 shots on the helicopters to keep the crew going. Two of the cameramen got sprained knees. Yeah. Sprained knees. From squatting up there for like 10, 12 hours at a stretch. And finally crashing. Maybe crashing after 20 hours, and somebody else grabbing the camera. Crashing right there on the stage, surrounded by the music, waking up during the Grateful Dead. Waking up, thinking, this will finish. We will finish this. But then you’d go under again…

Yeah. I remember huddling under this blanket, and people falling over me in the dark. Waking up during the Dead, yeah. The sky all dark and the light so bad they were pushing the film up to 1,000 ASA, trying to get something. Thinking, this has been forever. This has been all there ever has been…

After two days of this, you’d get into this…state. I remember during the Airplane’s set, I’d been up like 36 hours, and they started this song, and they were into it, and they were away over there, up there somewhere, into their thing. And 15 minutes later, still into it, and after half an hour, still, and you were floating, you were apart from whatever it was that was going on. And after like an hour you finally heard them coming back down into something else. And then you heard: You are the crown of creation…and you got it together again, remembering, hey, man, this is “Crown of Creation,” this is the Airplane. Because you’d even forgotten who they were, man…

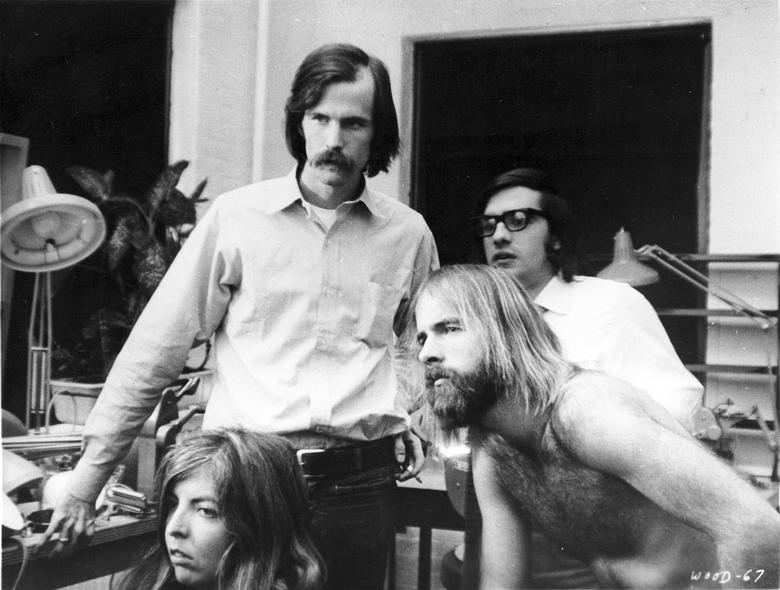

And this was in an Italian restaurant in New York, half a year later, and they were remembering. Martin Scorsese, the assistant director of “Woodstock,” sending his veal back to the kitchen because it was too rare, and remembering being at Woodstock. And Maggie Koven, eating lasagna: “I went to Woodstock as a schlep, and I came back as a schlep, but now I’m an assistant editor.”

Scorcese figuring it out: “We had 14 to 18 cameras at Woodstock, counting wild cameras. And when those three days were over, we came back with 50 miles of film. One hundred and twenty hours of film. it took us more than two weeks just to look at the rushes.”

Larry Johnson, the sound man, wincing: “I got two ear infections up there, man. One in each ear.”

People sitting around the table mopping up spaghetti sauce with French bread, drinking red wine. Michael Wadleigh, the director of “Woodstock,” is a 28-year-old flash who, before he started this one, shot documentaries of the presidential campaigns: “I shot Nixon, Humphrey, McCarthy. I remember I had to split from the Nixon campaign to go over to the Paris riots. I shot some stuff there. When I got back, Nixon waved at me. Where you been, Mike? he asked me. I just got back from the Paris riots, I said. How were they? he said. OK, I said; I got beat up by the cops.”

“What did Nixon say then?” Maggie wanted to know. Maggie, a lovely girl, long hair, big eyes, funny humorous mouth.

“Oh, nothing,” Wadleigh said. “He only nodded…”

And now everybody splits from the Italian restaurant and goes around the comer to this loft up on the fifth floor, served by a creeping freight elevator. A loft with a skylight and a lot of little rooms off the big one. “You know what picture was cut in this loft?” Scorcese says. “They made ‘Greetings’ in this loft…”

The loft is a crazy, jumbled place, like a Hollywood studio planned by Alice. All these earnest young girls and serious guys bending over their Kellers. The Keller Editing Machine. The finest editing machine in the world, and the only one you can use to cut three-screen stuff with eight-track synch sound, with 35-mm. and 16-mm. film on the same machine at the same time.

“This particular Keller here,” Wadleigh says, “is the machine Coppola cut ‘The Rain People‘ on. I think we have all of the Kellers in the country in this loft at this moment. We even brought one in from Canada.”

A serious-faced Japanese kid with a white technician’s smock is bending over his Keller like an acolyte at some strange technological dedication ceremony. He is trying to do something with the film they brought back on the Grateful Dead.

Shine on me…shine on me

“Stay back from the Keller,” Wadleigh tells everybody. “If you puke, don’t puke on the Keller.”

Everybody laughs. “Wadleigh hates the Dead,” Marty Scorsese explains.

“This is tougher than hell to cut,” the acolyte says. He steps back from his Keller now, letting it hurry ahead without him. On all three screens you see the Dead: the side screens show them in each profile, and the center screen has them head on. On each of the side screens, you can see the camera on the other side of the stage shooting the film you can see on the opposite side screen. And all, as the man says, at the same time.

“Tougher than hell,” the kid says. “What we have here is Pigpen singing Let your love light shine, let your love light shine on me, shine on me, shine on me. And singing that over and over. Singing the same goddam thing for an hour. And you put it on the Keller, you’re trying to synch three different pieces of film, and cut the hour down to maybe five minutes. And you’re trying to do it with film that was shot when it was so dark you could hardly see Pigpen, who in any event is holding the mike right in front of his face. So how you going to synch this goddam thing? You can’t even see his mouth.”

Commotion at the door. Bill Graham, proprietor of the Fillmore East and West, has arrived. Graham, the biggest honcho of rock music promotions in the country. He’s here to see rushes from the movie; rough cuts of acts he’s interested in, or books, or manages. All the acts in the movie will be paid; they’ll split up about $300,000, which will be about a third of the total costs. Graham is here to see how “Woodstock” is shaping up, and how his boys look on the silver screen.

Everybody goes into the projection room. It’s lined with thick sheets of soundproofing, and there is a big screen covering the opposite wall, and three big speakers lined up underneath it. On this end of the room, there are three projectors lined up and synchronized, so that even from the rushes you can see how the movie will look with the split screen technique. The soundproofing in the doorway is cut out in the shape of Mike Wadleigh with his hat on, something you figure out when Wadleigh walks through it and fits. People sit on sofas and on the floor, The lights go out and the first rushes are of Richie Havens.

The camera is right on Havens. In a shot from another angle, you can see a cameraman on his knees directly in front of Havens, his camera pointed right into his mouth. He’s inches away. Havens doesn’t have any upper teeth. Who gives a damn? He’s singing. When the lights go on again, Graham unwinds and says softly: “He’s powerful as a bitch.”

“So what do you think about the film?” Bob Maurice asks. Maurice, long hair, beard, soft thoughtful voice, is the guy who floated the $120,000 loan to finance the movie.

“You got something here,” Graham says. “How long is your rough cut so far?”

“We’ve got about seven hours of stuff we like,” Maurice says. “That includes about 60 per cent music, and about 40 per cent documentary aspects: the kids, the cops, the mud, the life style things.”

“Seven hours?” Graham says. “You gonna sell it in two parts like ‘War and Peace‘? Or what?”

“No, we’re gonna cut it down,” Wadleigh says. He’s standing in front of the projection room, quietly proud, because he can see the Havens’ footage really turned people on. He can see Graham was impressed. Hell, everybody was.

It’s strong. It’s the next generation of music documentaries, after “Festival” and “Monterey Pop.” Wadleigh explains that they had coverage. They had two, three, maybe six cameras at different places on the stage and in the audience at any given moment. All the cameras were simultaneously shooting complete sets. So, with synched sound, they can cut back and forth from one camera to another, or use split screen to show different parts of the same group at the same moment in a number. It’s like being inside the engine when the car is running.

“Each group you’d handle differently,” Wadleigh explains, while they’re rethreading the projectors. “Canned Heat we did in one unbroken 10-minute take, with the camera just wandering around the group. And then holding on Bear, Bob Hite, bobbing up and down. It was fun to figure out who was gonna take it next. For The Who, on the other hand, we used multiple cameras and did a montage with six screens. We could do that because we had such extensive coverage.”

Graham nods impressed. “I dunno,” he says in a speculative voice. “I’m thinking about closing the Fillmore this summer. This summer every jerk in the world is gonna have his own rock festival. Every two-bit promoter in the world is gonna try to get in on it. We might even close the Fillmore to live music this summer and open ‘Woodstock’ there. We could put in the screen; we have great sound equipment. Whatdaya think?”

“Not a good idea,” Maurice, the producer, says. “It’s better to have a small theater with 500-600 seats. You’ll have a longer run if people have to stand in line and be turned away. That way word-of-mouth gets out you have a hit. It’s horrible to say so, but it’s true.”

“I still like the idea of opening the movie in the Fillmore,” Graham says. “Rock should have its own Grauman’s Chinese. We could have cement impressions of Dylan’s elbows, Morrison’s schnook…”

The lights go down again.

“Now comes the socially redeeming message,” Bob Maurice says. “Arlo Guthrie.”

Arlo is shown arriving in a helicopter, getting out, walking up the long, long gangway, and looking out at the maybe 400,000 people who stretch away to the horizons of Woodstock Nation.

“Isn’t that far out?” Arlo says. “Too much. Dig it, man…”

“What’s this? What’s this?” Graham says in the dark projection room. “Who writes this guy’s dialog? Sounds like he memorized the Hip Dictionary.”

“Far out,” Arlo, on the screen, says again softly.

The screening lasts until midnight. Wadleigh runs through The Who, Santana, Jimi Hendrix. Hendrix is incredible. The camera is two inches from his fingers. He’s stretching the strings, punishing them, winging out on an improvisation of ‘The Star Spangled Banner’ where you hear rockets bursting in air…

Afterwards, Bob Maurice the businessman talking now. “I’m not sure you can do a story about this movie unless you talk to me,” he said. “The way this movie was conceived is the way a lot of movies are going to be made from here on out. The Hollywood studios are no longer plugged into the market, and they’re scared. There has to be an alternative source of films. Like us. They have to come to us. Believe me, Warner Brothers wouldn’t put up with us for one second if they could make this film themselves.”

Warner Brothers, Maurice explains, made a deal with them after Woodstock was over. They take over the film and distribute it, for a percentage. It will be released next month, assuming Wadleigh finishes the editing in time.

“No one else could have made a film, about Woodstock,” Maurice says. “No one else could have physically gotten there. And they wouldn’t have been willing to gamble enough money. But we knew. We used our own money, initially, because we knew after Woodstock was over somebody would want to buy it. And we did a daring thing. We extended ourselves for $120,000 credit.” He grins. “Which of course we didn’t have.”

Maurice says his job is to maintain “a defense network” around the movie, negotiating with the Warner people without letting them interfere with the making of the film. “They wanted an exploitation quickie, to come out as soon as possible,” he says. “We said no. We believe people will dig ‘Woodstock’ as a film, not because of the exploitation angles.”

He waves his arm in an arc to indicate the loft.

“All the people you see here,” he says, “were in the shooting crew. The people who shot the movie are involved in finishing it. This is our film. Sonja was there. Jean, over there, was an assistant cameraman. All the chicks were up there; none of these chicks are just…secretaries. Sure, the office has an atmosphere one could mistake for disorganization. It’s run informally, personally. But we get things done.

“The people from Warners were up here, and they were amazed. Sure, we have long hair, we speak the language. But we’re so far ahead of Hollywood in technical competence too, man. We don’t make movies because we have union jobs and tenure. We do it because we love it.

“We brought the first Kellers into this country, for example. A film like this would be impossible without them. Warner Brothers itself has equipment left over from the ’30s. Like, we have eight-track stereo equipment here. There’s not a single eight-track on the entire Warners’ lot.”