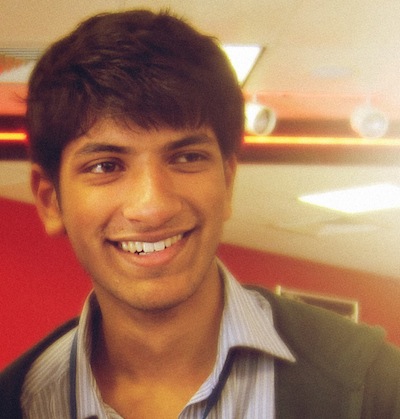

A compilation of some of my attempts at special effects, from when I was 9 to 19, inspired by the work of special effects wizard Ray Harryhausen, who died Tuesday at age 92:

Note: The following article was reworked from portions of a blog post that I wrote for the Far-Flungers earlier. The YouTube video is a compilation of my attempts at Harryhausen-esque special effects, from when I was between ages 9 to 19.

Ray Harryhausen told us, time and again, the story of how he saw the original “King Kong” (1933) on the big screen when he was just a kid, of how he was inspired by Willis O’Brien’s pioneering special effects, and of how that led him to his grand career in the field of stop-motion animation. In some sense, Harryhausen inspired me in the same way that O’Brien did him. I’m not exaggerating when I say that he changed my life.

It’s not just his work that inspired me. It was his life story. The story of a boy who simply watched a good movie, adored its special effects wiz, got to work with him, and then transcended everyone’s expectations and became a legend. Harryhausen’s journey was something to aspire to.

The first time I knew I was watching a Ray Harryhausen picture, it was 1960’s “The 3 Worlds of Gulliver.” I bought the DVD on a whim because I had an excerpt from “Gulliver's Travels” for English Literature and wondered how they’d pull off the Lilliputians on film. On the very first viewing I was so intrigued by the visual effects. There was something eerie about them; I knew they weren’t real … and yet they were real. The creatures were really there, unlike the monsters on the TV shows I used to watch now and then. The textures seemed authentic. The sequence where Gulliver battles a giant alligator particularly captured my imagination.

While most 9-year-olds in the ’90s would be oblivious to stop-motion (with CGI growing popular), I was in awe of it. There is a sense of life in stop-motion animated creatures. It’s the kind of life that much of CGI lacks. No matter how smoothly or realistically your computerized monster moves, there is something more subtle that stop-motion captures better. Harryhausen’s creations seem to be thinking, or feeling, not just moving and interacting with the real elements in the shot. His creatures have personality, an attribute that today’s visual effects still haven’t captured as well.

Is there something hidden in the real, physical contact between the fingertips of the artist and the model? Something that captures the essence of life in a way that programs and ones and zeroes cannot? Does that sound pretentious and condescending about CGI? Perhaps so. My apologies. But I still believe that there might be something hidden there, the same way that 2D hand-drawn animation has an extra level of life that 3D animation is still learning to project.

Also, no matter how crude a stop-motion model might be, it still exists. It occupies space and has weight. The Transformers, no matter how many cars they bump into and send flying, aren’t really there, and many times, they seem to be walking ‘through’ space, not occupying it.

One more thing that gives stop motion animation a distinction from other forms of animation is the dream-like quality it has. While 2005’s CGI “King Kong” was a wonderful work of modern computerized special effects, the 1933 film has a nightmare quality to it that CGI can’t quite achieve. Look at the realistic Pegasus from the recent remake of “Clash of the Titans” and then look at Harryhausen’s version. Tell me, which one left you smiling?

There is a spectacular sequence in Harryhausen’s most popular picture “Jason and the Argonauts” in which Jason and his crew do battle with seven sword-fighting skeletons. This is surely one of the greatest special visual effects sequences in motion picture history. There are shots in which the screen is filled with the men fighting all seven skeletons. This means that Harryhausen would have to move each of the seven skeletons such that they match the chaotic live action footage of the men mock-fighting, shoot a frame, move them again one by one, shoot a frame, and so on. Twenty-four frames make one second of action. It is hard to imagine how Harryhausen did all the special effects in his films solo (save for his first and last films, on which he had help). And it is not surprising that the skeleton sequence from “Jason” took him four months to complete.

And to be sure, he could’ve simply said, no, seven skeletons are too much. But, in fact, he came up with the idea for the sequence, as he did for his many others. He drew the very first piece of concept art for the set-piece, knowing very well that it would take him months of work to realize.

This man never made the job easier for himself. Flying creatures? Why not? Flying animals? Of course. Creatures interacting with water? You bet. He took no short cuts, and the whole of the fantasy film world is all the better for it.

If you have not watched any of his films, at least YouTube the brilliant effects sequences, which are always the highlights of the films anyway. That’ll convince you how ambitious he was with his art. Try the scene where the cowboys try to “rope” Gwangi, in which Harryhausen had to painstakingly match the ropes on the live action footage to the ropes on his stop-motion model. Or the tug of war in “Mighty Joe Young,” using a similar technique. Or the sequence with the giant bird from “Mysterious Island,” which works hilariously well with Bernard Herrmann’s goofy score. Or the Washington destruction scenes in “Earth vs. the Flying Saucers.” Or “It” from “It Came From Beneath the Sea.” Or Pegasus in “Clash of the Titans,” or Medusa from the same film. Or anything from “The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad,” my personal favorite film of his.

You can see Harryhausen’s influence on so much of today’s fantasy film world, from the work of Spielberg (there are references in “Jurassic Park“) to the films of Tim Burton (he is one of the strongest supporters of stop-motion today; the piano in “Corpse Bride” has a name plate that reads “Harryhausen”) to Peter Jackson (who remade Willis O’Brien’s “King Kong” into one of the greatest fantasy adventures in recent years) to even Pixar (the restaurant in “Monsters, Inc.” is called “Harryhausen’s”).

Any battle between humans and skeletons in any movie since “Jason and the Argonauts” surely owes much of its choreography and ideas to Harryhausen. And consider how many movies have done it: the first “The Pirates of the Caribbean,” “The Mummy” remake, Sam Raimi’s “Army Of Darkness,” to name a few. None of those sequences, with all their leaps and bounds in technology, hold a candle to “Jason”‘s skeleton battle.

In an attempt to recapture some of the magic that amazed me, I tried stop motion myself. I had a very basic idea of what stop motion was from a few documentaries I saw among the bonus features of the DVDs my mother bought me. Every Columbia DVD release of his films had the invaluable “The Harryhausen Chronicles,” a documentary that every fan of his has surely watched, narrated by no less than Leonard Nimoy. The documentary, which covers nearly his entire career, explained stop motion in a very rudimentary manner, but that was enough to get me started.

I unearthed a rarely used Sony Handycam we had in our home and began my experiments. This was back in the days of cassette tape recording, so the editing and special effects were all done in camera, while shooting. The DVD documentaries were quite informative, but no one ever taught me anything or actively encouraged me to do it. I was my own student and teacher, and it was my own interest that fueled my persistence. All I had was a camera that recorded on tape. How did I shoot the video, frame by frame? I would quickly double-click the “record” button, hoping that the little shots I was getting were all around the same length, and short enough. They really weren’t, but back then it worked for me.

Among the clips in the homage compilation are my crude imitations of Harryhausen’s Cyclops, my cruder imitation of Kong’s battle with the snake from O’Brien’s “King Kong,” my experiments with using glass as a surface for animation, and so on.

The last clip in the compilation, which I completed only just a month ago, was my first attempt at weaving live action and animation together and making elements in the real world and the animated world interact, much like Harryhausen did with his Dynamtion process. It was just a visual effects test to see if I could pull off a complete Harryhausen-esque film on a shoestring budget. Of course, it is true that the real Harryhausen films were done of shoestring budgets.

Though Harryhausen is now remembered for being involved with some of the greatest adventure films of their kind, if you really look back at his career you’ll feel that he deserved better films and higher budgets. His films were so low-budget that in several instances, the full extent of his vision wasn’t realized. It is now popular trivia that the octopus in “It Came From Beneath the Sea” actually had only six tentacles because they couldn’t afford to build a model with eight. Though the films have inspired several of us, it was, in most cases, only the special effects that kept the films from being mediocre B-movie fare. It is sad that he didn’t get to work with greater talents and resources than he did, if that isn’t too condescending a thing to say. Imagine what would have come out of such collaborations.

This master of animation — no, imagination — was snubbed by the Academy year after year, his films not even getting nominations for their special effects, until long after his retirement when they gave him an honorary Oscar, which I suspect was more of an apology than a token recognition. I’ve read somewhere that Harryhausen reckoned his films didn’t get recognized by the Academy when they were released because they were shot in Spain, and not in Hollywood. Shot in Hollywood or Spain, the *real* movies were actually shot in London. Harryhausen did most of his animation work there, where he lived since the ’60s.

When I heard that Harryhausen had died, I froze for a second. This might sound like a terrible thing to say, but I’d often wondered how I’d react to his death (I had these thoughts only after I read about his reaction to Willis O’Brien’s death). When I was younger, I assumed I’d cry or something of the sort. My real reaction, just a few hours ago, was very different. I simply watched clips from his older films and smiled. And it felt like the clips smiled right back.

But my world feels a little less bright. Earlier this year, Roger Ebert left us. He was the greatest human being I’ve known, and he intervened in my life and made it a whole lot better. Harryhausen did that in a less direct way. A little more than two years ago, my father died.

You know that corny metaphor they keep using in the movies, the one about people dying and becoming stars? Truth is, with each of these deaths, I sense a star fading from my sky. The world feels a little less special.

Regarding today’s blockbusters, we mourn the loss of good storytelling when the visual effects sequences upstage the human characters and the emotional dimensions to the picture. With Harryhausen’s work, however, the visual effects almost always did upstage the human characters, but that’s only because his creatures were, simply put, the better characters. They lived and breathed and explored and fought and died, and they had goals and desires that you could discern from every subtle movement they made, and they live on in our imaginations, and have spawned today’s visual effects.

Ray Harryhausen captured our imaginations and I doubt he will ever let go.