When I turned 16, I did not receive a new car or an ostentatious party or the revelation of heretofore unknown powers that would allow me to overthrow the confusingly designed dystopian society to which I belonged. Instead, I got something better—I got my mind permanently blown through the gift, courtesy of my Uncle Edward, of a VHS tape of “Eraserhead,” David Lynch‘s one-of-a-kind debut feature that had become a notorious cult classic ever since its 1977 debut. At this time, I had certainly heard about the film—I had read the tantalizing pieces on them in such invaluable books as Danny Peary’s “Cult Movies” and J. Hoberman & Jonathan Rosenbaum’s “Midnight Movies”—and I had seen Lynch’s subsequent efforts “The Elephant Man,” “Dune” and the jaw-dropping “Blue Velvet,” and was therefore certainly primed to finally experience his maiden work at last since none of the video stores in my area were adventurous enough to stock it. My only worry when I settled in to watch it—with my entire family, for reasons lost in the mists of time and a decision that would quickly prove to be spectacularly ill-advised—was that I had built it up so highly in my mind by that point that I feared that it would be almost impossible for it to match my expectations.

Needless to say, the film not only matched my expectations, it exceeded them in ways I never dreamed could be possible. Here was a film that took elements that one might have encountered in other movies in the past—black humor, gore, surrealism, erotic imagery, gorgeous black-and-white cinematography and oddball performances—and presented them in such a unique and deeply personal manner that the end result was something that literally looked, sounded and felt like nothing that had ever come before it. I may not have been able to explain any of it when it was all over but for every single one of its 89 minutes, I was absolutely mesmerized. The amazing thing is that since that first viewing, I have seen the film countless times in any number of situations—on that VHS tape and on DVD, in theaters during normal working hours and at midnight, on cable and now on the fabulous new Blu-ray special edition from the Criterion Collection (featuring such bells and whistles as a 2001 documentary featuring Lynch discussing the production history of the film and amazing behind-the-scenes footage, new interviews with members of the cast, six short films directed by Lynch and a gorgeous new 4K presentation of the film itself). Every time I watch, I remain just as enraptured with the film and its mysteries, which have held up over the years to such a degree that I suspect that to even attempt a basic synopsis would drive me to madness in attempting to convey its magic in mere words.

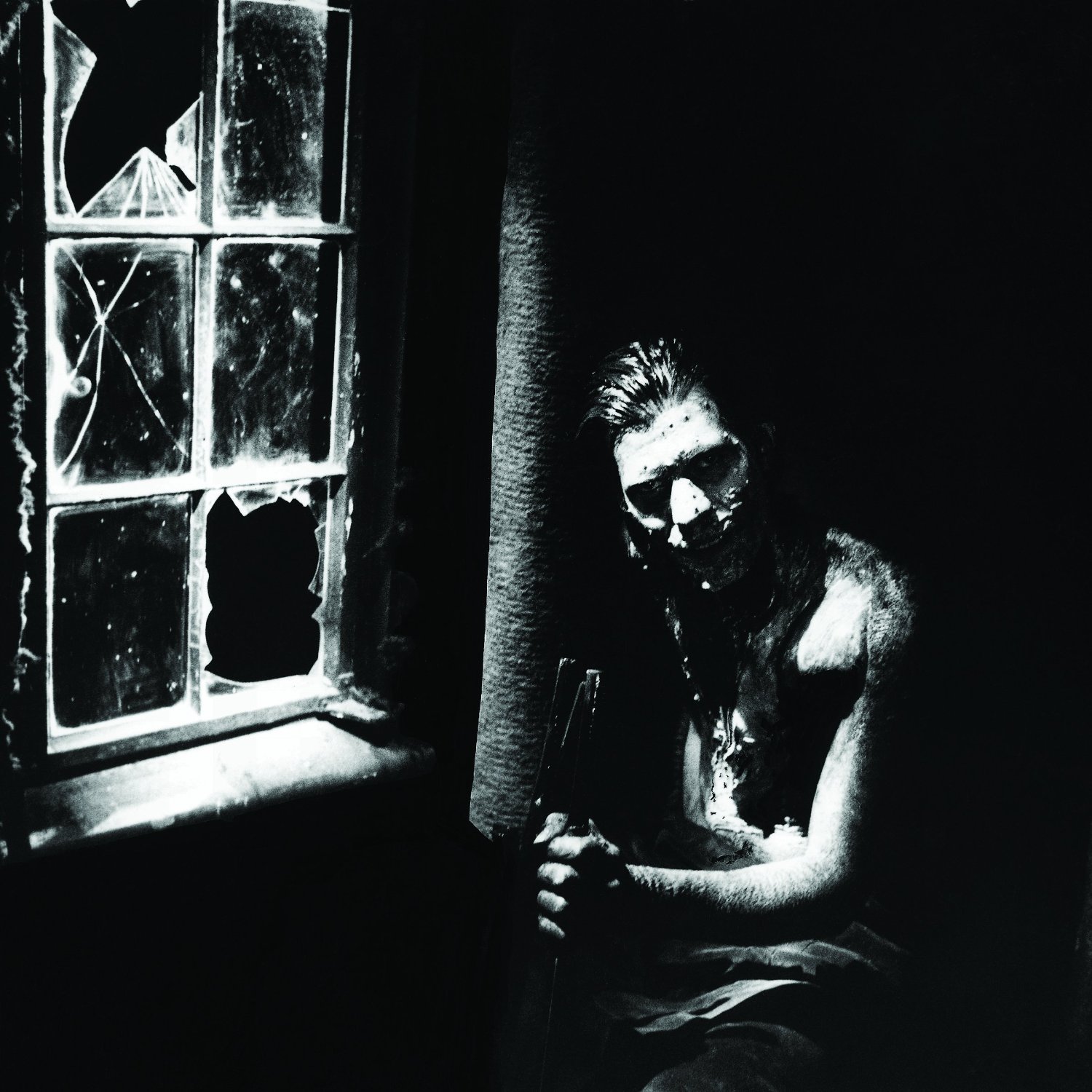

Set in a grim, unnamed world, during what is presumably at least a mildly post-apocalyptic age and definitely on the wrong side of the tracks regardless, the film focuses on Henry Spencer (Jack Nance, in the first of what would prove to be many collaborations with Lynch), a label printer whose uber-nerdish look and demeanor is topped off, literally, by a hairdo that makes it seem as if he is receiving constant electrical shocks. One night, he returns home to his beyond-shabby apartment to learn that he has been invited to dinner with his girlfriend, Mary X (Charlotte Stewart), in order to meet her parents. In the most deranged variation of the boyfriend-meets-the-family trope ever produced, Mary’s mother makes Henry answer any number of embarrassing questions—several of them twice—and even licks his face at one point. Her grandmother sits in the corner in a catatonic state; her overly jovial dad brags about how he has no feeling in his left arm; there is a litter of puppies nursing on the floor; dinner consists of tiny man-made chickens that spurt hideous goo whenever someone cuts into them. To top all that off, it is revealed that Mary has given birth to a premature baby (“They aren’t even sure that it is a baby!,” Mary wails) and her parents insist that the two get married and take it home with them.

Ah, the baby—how to describe it? Imagine a cross between a fetal version of E.T. and some form of skinned ruminant that has been plagued with an eternal cold that causes it to cry, whine and spit up various forms of goo practically around the clock. After presumably a couple of days of this grotesque version of domestic tranquility, Mary flees for home and leaves Henry in charge at precisely the point where the child becomes seriously ill. Oddly enough, Henry pulls it together enough to nurse the kid back to something resembling health, but, after a series of increasingly twisted visions/hallucinations involving Mary (Judith Anna Roberts), the prostitute across the hall, who appears on a stage to sing about how wonderful things are in Heaven while stomping sperm-like creatures with her feet, he is finally driven to do something hideous to his own flesh and blood.

The above description may more or less describe what happens during “Eraserhead” (though I see I have neglected to mention such elements as the bookend appearances by a horribly burned man who sits at a window yanking a crank that sends more of those sperm-like creatures into the world and the extended dream sequence that eventually give the film its name) but it hardly begins to suggest how it happens. Utilizing hallucinatory production design and special effects, haunting black-and-white cinematography by Frederick Elmes and Hebert Cardwell and an astonishingly complex soundscape by designer Alan Splet that combines industrial noise, leaky steam radiators and the music of Fats Waller, Lynch plunges viewers into a world unlike any other in the history of film—imagine the cinematic equivalent of the third sleepless night after being struck down with the world’s nastiest head cold—and one that leaves viewers feeling as adrift and alienated as Henry himself.

Although the end results may prove to be too alienating for some viewers, they are nevertheless astonishing to behold in terms of their formal beauty and are even more so when one considers that the film was shot piecemeal over the course of a couple of years, first with funding provided by the American Film Institute and, when that ran out, with funds supplied from such sources as production designer (and Lynch friend) Jack Fisk, Fisk’s wife Sissy Spacek and money Lynch earned from a paper route. (In one of the DVD supplements, Lynch points out a moment where Henry opens a door to note that the scene of him entering the room itself was shot more than a year later.) Despite the gaps in its production, the film as a whole creates a singular mood and sustains it from the first frames to the last.

That mood has lasted from the time of its premiere until today and much of that is due to the fact that, unlike virtually every other classic film, “Eraserhead” is a work that resolutely defied all attempts to explain either what it means or even the mechanics of how it was produced. The script is a brilliant mixture of narrative and experimental structure that provides just enough storytelling points to give viewers something to hang on to, at least in the early going, before completely subsuming them with its more avant-garde moments later on. The result is a film in which all of the elements may not necessarily add up but which nevertheless maintains a logical consistency throughout that is too often lacking in a lot of experimental cinema—even if you don’t quite get what you are seeing, you never get the sense that Lynch is just making stuff up as he goes along in order to score an immediate visceral impact to the detriment of everything else.

At the same time, while some have attempted to explain “Eraserhead” as Lynch’s nightmarish take on the perils of domesticity or as a pro or anti-abortion tract, it is a testament to the power and purity of his vision that even after all of these years, it still cannot simply be reduced to a bunch of talking points. To “explain” “Eraserhead” would be like cutting a drum open to see what makes the noise—you may get your answer but you tend to ruin the drum in the process. Thankfully, this is a drum that should continue to make noise for decades to come. (Significantly, even though this Blu-ray is filled with bonus materials that tell the story of how the film came to be, it nevertheless manages to leave its deepest mysteries—from what it is all “supposed to mean” to the exact mechanics behind the presentation of the baby—as perplexing as ever.)

When “Eraserhead” premiered in 1977, it received largely poor reviews and minuscule returns at the box office and might have drifted off into obscurity were it not for the efforts of distributor Ben Barenholtz, whose championing of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s “El Topo” a few years earlier made it a cult sensation through regular screenings on the then-developing midnight movie circuit. Based on little more than a gut feeling, Barenholtz took the film on, and, even after its initial playdates met with little success, he continued to have faith in it and convinced a theater owner in New York to keep it on until it eventually developed a loyal fan base that kept it playing for the next few years and made it one of the most (in)famous of all cult movies. (Much like the image of Harold Lloyd dangling from the clock, even people who haven’t seen the film certainly recognize the iconic image of Henry and his inimitable hairdo.)

Today, this would be all but unheard of—even if the midnight movie scene existed as it once did, a film of this sort would almost certainly be relegated to a couple of underground festivals and even if a distributor were to take a chance on booking it commercially, it is unlikely they would have the patience to give it a chance to attract viewers before yanking it in order to play something with a better chance of attracting audiences. As a result, watching “Eraserhead” today can be a somewhat melancholic experience in this regard for those who once experienced it in its after-hours glory and realize that the time when something like this could thrive has long since passed. (This is ironic considering that the film is one of the few midnight movies that actually plays well at home—provided that your home system is set up properly (and the Blu-ray offers up a calibration test to help with that)—as it is arguably only one that does not exactly lend itself to the collective moviegoing experience in the manner of such contemporaries as “The Rocky Horror Picture Show” or “Pink Flamingoes.”)

David Lynch would, of course, go on to become one of the most controversial and acclaimed filmmakers of our time and his idiosyncratic visions would even strike chords with mainstream audience, as evidenced by the commercial success of such projects as “The Elephant Man” (which he was hired for largely due to producer Mel Brooks’s fascination with “Eraserhead”), “Blue Velvet,” “Twin Peaks” and “Mullholland Drive.” As excellent as his subsequent films would prove to be, “Eraserhead” remains Lynch’s purest work of art. Granted, the film may not be for everyone (my mother considers the title to be a dirty word, though she did dig “Mulholland Drive“) but for those who manage to find themselves on its admittedly peculiar wavelength, “Eraserhead” continues to be a stunning work that quite simply redefines what a feature film can do both to and for audiences willing to take the journey.