I’ve always had the feeling that there are some who think black films didn’t start until the mid-1980s with the appearance of Spike Lee and his debut “She’s Gotta Have It.” Some others may think that black movies didn’t exist until the advent of the blaxploitation films of the early to mid-1970s, while others may believe it started with the “L.A. Rebellion” group of black filmmakers from UCLA Film School of the ’70s and early ’80s, such as Julie Dash (“Daughters of the Dust“) and Charles Burnett (“Killer of Sheep,” “To Sleep with Anger”).

The reality is that black films started with the popularization of cinema 100 years ago. In fact, some 500 or so black films, better known as “race” films, were made and released between 1915 and 1952.

Unfortunately, since these race films were not a priority, there were no preservation efforts made to save these projects and most are lost forever. Those that remain are almost always in deplorable condition—many times whatever prints that exist are DVDs or 16mm duplicates of duplicates and have degenerated into images of a fuzzy mush lacking in detail and sharpness.

These films were created by pioneering white and black filmmakers to provide entertainment and make a buck or two from the under-served audience of black filmgoers, most of whom saw these films in segregated theaters in the South. But, especially for early black filmmakers such as Oscar Micheaux and brothers Noble and George Johnson, these films represented something deeper.

They saw them as an alternative to the usual movie images of African-Americans that black people were forced to see in degrading and humiliating stereotypes—these films were an attempt to present a more balanced view of black life and culture. Though many titles were, in effect, low-budget copies of white films that were being made at the time, it was still a revelation and a relief for black audiences to see themselves on the screen larger than life, being heroic, charming, intelligent, brave and romantic. They were detectives, musicians, soldiers, cowboys, professors and teachers—men and women of position and prestige. Films dealing with the educated middle class and well-to-do black people on the screen was a reality for some, but for many others it was something to aspire to.

Many of these films also dealt with issues unique to black audiences. They addressed issues such as racism, lynchings, colorism and poverty among other problems, covering a whole wide swath of genres from dramas to comedies to westerns to musicals, and even a couple of horror films as well.

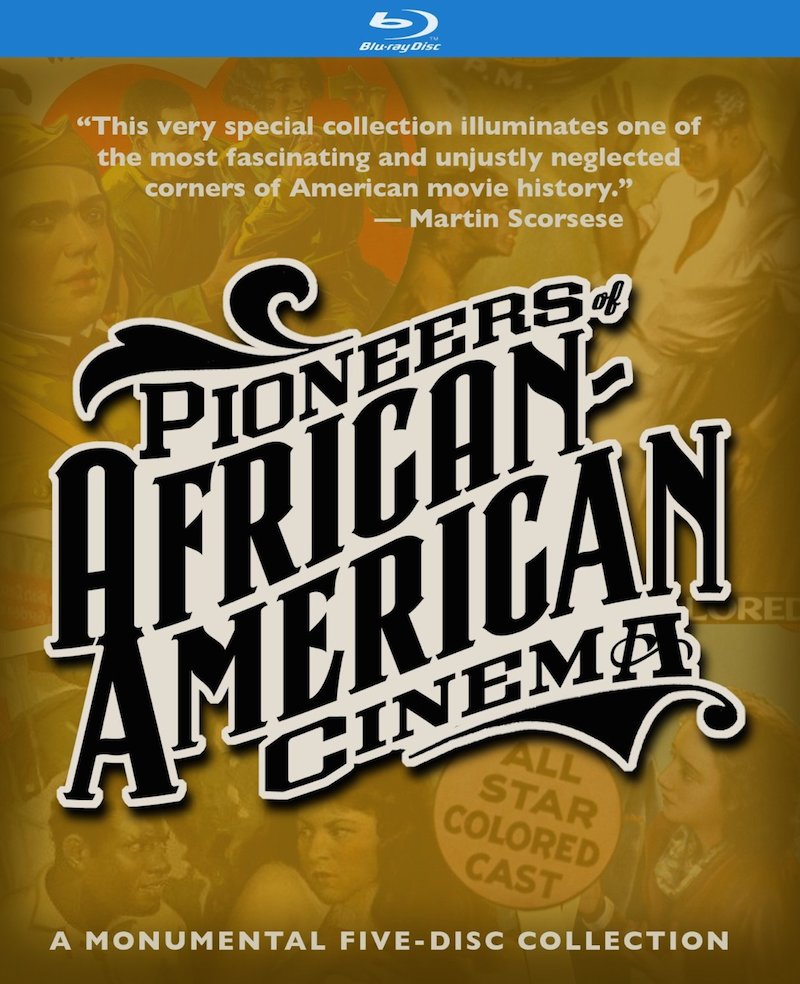

After years of painstaking restoration work, even establishing an online crowdfunding campaign to help with the financing, Kino Lorber has released their outstanding and groundbreaking five-disc DVD and Blu-ray set, “The Pioneers of African-American Cinema.”

Co-curated by Professors Charles Musser of Yale University and Jacqueline Stewart of University of Chicago and produced by Bret Wood and executive produced by Paul Miller (also known as DJ Spooky), the set is not only one of the most vital DVD releases of the year, it is, more importantly, historic. For the first time, a collection of race films, about 26 features and shorts, have been wonderfully restored and placed into their proper context in regard as to their importance and meaning.

Though some of the films, despite their restoration, are in some cases incomplete or partially deteriorated or beyond any salvation, they all give valuable insight to what is still an overlooked aspect of cinema history. They reveal a world from the not too distant past, where filmmakers were discovering the transformative power of the cinema and how it could reflect the lives, personal dreams and longings of the audience. These films, though as imperfect as they may be, are a moving testimony of black culture and history that is American to its core and that has shaped the destiny of this country.

Though there are many titles in this collection, the directors that are represented of the most prominence are African-American filmmakers Oscar Micheaux, Richard Maurice and Spencer Williams. Maurice is in some ways the most fascinating of the three as there is literally very little known about him. Based in Detroit, he is known to have produced and directed five features though his bizarre feature 1928 silent film “Eleven P.M.” is the only one that exists.

On the surface, it’s a simple story of a poor musician (played by Maurice himself), who tries to save a young orphaned girl (Wanda Maurice, Maurice’s daughter?), from being taken advantaged of by a local gangster. However, the film is slickly made with some raw, gritty street shots of 1920s Detroit when it was in the midst of Great Migration, footage that features black people from the South moving to the North for better opportunities and oppression.

“Eleven P.M.” takes a very weird turn at the dramatic climax, resulting in a completely surrealistic shift in tone with oddly disturbing images. Only after that comes the final plot twist, which some may find disappointing or clever. The question is: Does “Eleven P.M.” reflect Maurice’s approach to his films, or was it a strange off-beat experiment separate from his other films? Unless by chance some surviving prints of his other movies are found, we shall never know.

Micheaux, an Illinois native born in 1884, is considered by many to be the great early pioneer of black directors. After travelling around the country pursuing various careers, including a Pullman porter and homesteader in North Dakota, Micheaux started making films in 1919. First based in Chicago before moving to New York a few years later, Micheaux made an estimated 40 films over a 30-year-period until his final film in 1948, “The Betrayal.” A three-hour remake of his first movie, “The Homesteader” shot in and around Chicago, is now sadly lost like many of his projects.

Michaeux, who has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, has been crucified for his lack of technical expertise (due to his extreme low budgets he was forced to often to use single takes and hired inferior film crews on the fly), but while his awkward, disjointed screenplays were also accused of colorism—favoring lighter-skinned actors and actresses for his leads, while villains and wanton, evil women were usually dark-skinned—one cannot deny that he was extraordinary ambitious and prolific. His films were a response to this audience’s dreams and aspirations as well as their concerns.

Michaeux, who has nine films in the set, also addressed issues that Hollywood films refused to acknowledge such as racism, lynchings (as he did his 1920 film “Within Our Gates,” included in the set) and the conflicts between Southern rural blacks and their Northern cousins.

And because of his complete freedom outside of the Hollywood system—that would not have let him in anyway—he was free to tackle certain issues such as sex. For example, in his bafflingly offbeat, 1932 early sound film mystery thriller “Ten Minutes to Live,” we witness a woman taking off her clothes and putting on her evening dress with some erotic mild nudity, something that never would have never been allowed in a Hollywood film.

In this set, Micheaux is also represented with his 1933 film, “The Girl from Chicago.” It’s a narratively-broken crime movie dealing with the pursuit of criminal by a Secret Service agent, who has just returned to the U.S. after working for several months with Scotland Yard, and then later—in a totally unrelated story—clearing his fiance’s aunt of the murder of a numbers runner. The fact that Micheaux had the progressive idea of presenting a black man as a Secret Service agent who worked with Scotland Yard—when none existed in real life—must have been a thrill for black audiences back in 1933 used to seeing black men in degrading subservient roles in Hollywood movies, despite the film’s clumsy plot mechanisms, poor dialogue and threadbare production values.

Spencer Williams, who may be better known to older people as Andy from the “Amos and Andy” TV show from the 1950s, has a long and varied career as a writer and director in race films. During the 1940s he made a series of films, mainly comedies and musicals, but his two standout works, “Go Down Death” and “The Blood of Jesus,” are in the set. They’re simple but powerful religious allegories, using uncomplicated narratives to tell of the eternal struggle of good vs evil and redemption. His implementation of footage from other films to visually underline the spiritual messages in his own is powerful, and his simple surrealistic images give his projects a sincere poignancy.

Williams’ 1946 movie “Dirty Gertie from Harlem USA” [pictured above] is a retelling of W. Somerset Maugham’s story “Rain,” in which a loose-living entertainer comes into conflict with a holy roller preacher who sets out to have her repent or destroy. The film captures the rustic atmosphere and mood of its period, and its underlining message—of a woman who is ultimately punished for her confident and almost mercenary sexuality—is powerful at the film’s tragic end.

Among the other titles in the set, one unique standout is the 1926 silent film “The Flying Ace,” directed by a white director Richard E. Norman and shot in Florida. It’s a fast-paced and genuinely exciting feature, involving a returning World War I flying ace and former investigative detective who returns to his Florida hometown and gets involved with the mystery of a kidnapped railroad employee and the weekly payroll. Effectively using the swampy, natural environment of a sweltering Florida countryside, the film moves with a fast pace. It leads up to an intercut car vs. bicycle and plane chase while our hero is ably aided by his one-legged sidekick, who practically steals the film with his amazing physicality and stunt work.

With 26 films in the set, there are too many features and shorts to adequately discuss in detail, but “Pioneers of African-American Cinema” is an essential and groundbreaking Blu-ray set. It’s more than worthy to be considered one of the most important and valuable releases of the year, as it brings to light an important aspect of black and cinema history that must not be forgotten or ignored.

PROGRAMMING NOTE: Turner Classic Movies (TCM) will be showing some of the films from “Pioneers of African-American Cinema” on July 31 starting at 8:00pm (7:00pm Central) and running all night. Prof Jacqueline Stewart of the University of Chicago co-curated the collection and will be co-hosting these broadcasts with Ben Mankiewicz.

Disc 1:

“Two Knights of Vaudeville” (1915, 10:56)

“Mercy, the Mummy Mumbled” (1918, 13:29)

“A Reckless Rover” (1918, 14:07)

“Within Our Gates” (1920, 73:41)

“The Symbol of the Unconquered: A Story of the Ku Klux Klan” (1920, 59:15)

“By Right of Birth” (1921, 4:40)

“Body and Soul” (1921, 93:01)

“Screen Snapshots” (1920, 1:40) – Taken from newsreel footage of Oscar Micheaux on the set of “The Brute.”

Disc 2:

“Regeneration” (1923, 11:33)

“The Flying Ace” (1926, 65:48)

“Ten Nights in a Bar Room” (1926, 63:56)

“Reverend S.S. Jones Home Movies” (1924-1928, 16:11)

“The Scar of Shame” (1929, 86:36)

Disc 3:

“Eleven P.M.” (1928, 66:42)

“Hell-Bound Train” (1930, 50:57)

“Verdict: Not Guilty” (1933, 8:41)

“Heaven-Bound Travelers” (1935, 15:18)

“The Darktown Revue” (1931, 18:26)

“The Exile” (1931, 78:26)

“Hot Biskits” (1931, 10:03)

Disc 4:

“The Girl from Chicago” (1932, 70:43)

“Ten Minutes to Live” (1932, 57:58)

“Veiled Aristocrats” (1932, 44:10)

“Birthright” (1938, 13:39)

Disc 5:

“The Bronze Buckaroo” (1939, 58:03)

“Zora Neale Hurston Fieldwork Footage” (1928, 3:02)

“Commandment Keeper Church” (1940, 15:41)

“The Blood of Jesus” (1941, 56:29)

“Dirty Gertie from Harlem U.S.A. (1946, 60:24)

“Moses Sisters Interview” (1978, 32:05)

EXTRAS

Booklet Essays by Paul D. Miller, Charles Musser, Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, Rhea L. Combs, Mary N. Elliot, and a filmography.

Disc 1:

“An Introduction” (7:30) An overview of disc content, featuring film historians Jacqueline Najuma Stewart and Charles Musser. Sound quality is iffy, but the information is valuable.

“The Films of Oscar Micheaux” (8:49,) Professor Musser discusses the work of the pioneer moviemaker.

Disc 2:

“The Color Line” (5:17) Professor Musser’s thoughts on racial collaboration in film.

“Ten Nights in a Bar Room: An Introduction” (4:14) – Musser offers an explanation for the film.

“About the Restoration” (8:06,) An overview of the recovery effort, hosted by Bret Wood. Also of interest are examples of moviemaking mistakes that remain in the pictures, with disc producers resisting the urge to correct these admittedly humorous issues.

Disc 3:

“Religion in Early African-America Cinema” (6:45) Professor Stewart, offers an historical perspective on depictions and criticism of faith in the collected films.

“Eleven P.M.: An Introduction” (3:04) – Professor Musser discusses of the Richard Maurice film.Interview (5:08)

Film historian S. Torriano Berry inspects the work of James and Eloyce Gist.

Disc 4:

Trailers for “Veiled Aristocrats” (4:07) and “Birthright” (3:52) .

“We Work Again” (1937, 15:11) A newsreel focusing on WPA projects across America.

Disc 5:

“Tyler Texas Black Film Collection” (1985) is a promotional film hosted by Ossie Davis.

“The Films of Zora Neale Hurston” (1:50) Library of Congress archivist Mike Mashon discusses the discovery of a forgotten filmmaker’s works

“The Films of Spencer Williams” (6:58) Prof. Stewart identifies creative film directing accomplishments better known as the former star of TV’s “Amos ‘n Andy.”

“The End of an Era” (4:42) Prof. discusses the reasons for the end of the early black “race” film movement in the early 50’s after several decades

To purchase “Pioneers of African-American Cinema,” click here