French actress Marion Cotillard would seem an odd choice to star in a film by the Belgian co-directing filmmakers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardennes. She’s been the darling of international directors including Arnaud Desplechin, Ridley Scott and Tim Burton, and since her Oscar win for Olivier Dahan’s “La Vie en Rose,” has been in demand globally, working for Michael Mann (“Public Enemies“), Woody Allen (“Midnight in Paris“), Jacques Audiard (“Rust and Bone”), Christopher Nolan (“The Dark Knight Rises“) and James Gray (“The Immigrant“).

Within roughly the same period of time, the Dardennes brothers have twice won the Palme d’Or at Cannes (for “Rosetta” and “The Child”) along with a host of other prizes. Their low-key, distinctively realist work has addressed subjects including child abandonment, juvenile delinquency, and illegal immigration, often utilizing a small clutch of regular actors.

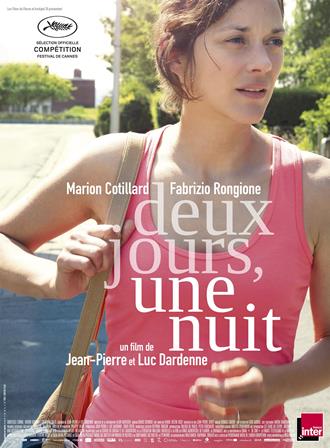

The Dardennes’ “Two Days, One Night” premiered in Cannes competition today, starring Marion Cotillard as Sandra, a young working class wife and mother whose job is on the line at her small factory as the result of an announced layoff. Management has required Sandra’s sixteen co-workers choose by vote between receiving a hefty bonus and retaining her job. To complicate things further she is just due to return from a four-month sick leave for depression, and is still fragile and weepy, dependent on anti-depressants.

That’s the setup, but the film’s story is essentially a journey toward the clarity and self-realization that Sandra lacks in her life. Every Dardennes film is some kind of mission or journey, even if the physical distance traveled is only a few blocks on a bike or in a baby stroller. Whether it’s the search for a father, the recognition of a son, or achieving a sense of belonging, their characters must quite literally go from here to there for a resolution. So it is with Sandra, who spends a desperate weekend hunting down her co-workers to ask for their votes.

To her great credit, Cotillard disappears completely into the role. This is not a slumming turn by an international star, but an appropriately underplayed performance. Sandra’s need may be the driving mechanism of the plot, but the collective economic circumstances of the ensemble of workers portrayed remain the focus of the film.

With the help of her husband Manu (Dardennes regular Fabrizio Rongione), Sandra seeks out each voting co-worker at home. The Dardennes brothers are fiends for detail, and so much on display here is eminently telling without being picked out or underlined. It’s especially significant that each of the homes that Sandra visits is middle class. There are neat, pretty townhomes with nice yards, cozy apartments, kids and loaded shopping bags as evidence of leisure and hard-won prosperity.

What’s at stake in this two-day journey from door to door is obvious. Prosperity is as precarious for each of her colleagues as it is for Sandra and her husband; if one wins, someone else loses. Come Monday morning, “Two Days, One Night” presents Sandra and her co-workers with the choice between moral victory and a deal with the devil.

Chinese director Zhang Yimou is here in Cannes with new film “Coming Home, which screens as a special event out of competition. The film stars Gong Li, the actress with whom he made a string of international hits including “Red Sorghum,” “Ju Dou” and “Raise the Red Lantern,” and new discovery Zhang Huiwen.

Lauded as the foremost of China’s Fifth Generation directors, Zhang is now probably more widely known around the world as the man who staged the spectacular opening and closing-night ceremonies for the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics. He’s a multi-talented artist and a star-maker who has notoriously been involved in the past with leading lady-discoveries Gong Li and allegedly Zhang Ziyi. [Zhang is a common surname, and Zhang Yimou, Zhang Ziyi, and Zhang Huiwen are not related.]

A rhapsodic description of the quality of Zhang Huiwen’s eyes in Zhang Yimou’s director’s notes on the film got some of us talking while waiting for the screening to begin. I was sitting with Time Magazine critic Richard Corliss, his wife Mary Corliss, both writing for Time.com from Cannes, and longtime China-watchers, and we couldn’t help speculating whether this new discovery or “rising star,” as the notes call her, being seen in her first role in “Coming Home,” is also the director’s latest muse.

Gossip aside, “Coming Home” is a somber and emotional film about memory set during and after China’s Cultural Revolution. The film reaffirms Zhang Yimou’s ability to zero in on the limited world of a family against the background of historical events after large-scale action-filled period epics including “Curse of the Golden Flower” and “House of Flying Daggers.” It also provides Gong Li and Zhang Huiwen with plum roles.

As “Coming Home” begins, mother Wanyu (Gong Li) and her teenage daughter Dandan (Zhang Huiwen) a talented dancer, are confronted by the news that Yanshi (Chen Daoming), husband and father respectively, has escaped his reeducation camp and may be trying to find them. A dedicated child of the Party, Dandan opts to protect herself, and stands firm against a possible reunion with the fugitive father she doesn’t know.

Zhang Yimou is a superb visual stylist. With great subtlety, his character’s faces are often seen in shadow, with light glinting off hair or features barely outlined, an apt choice in which each character loses much to the vagaries of politics and history. The set piece in which fugitive Yanshi attempts to connect with Wanyu at a large urban train station is fast moving and intricately choreographed. With roaring sound, two endless coal trains speed on opposite tracks, flanking platforms zigzagged by stairways and bridges. The noise, the crowds, and the chase reach a crescendo that brings the first portion of the film to a crushing conclusion.

In setting the major portion of the story at two different times in a “new,” post-Cultural Revolution China, Zhang depicts a family that has suffered damage that can never be repaired. Yanshi eventually returns, officially rehabilitated, but the wife he knew has departed in spirit, having lost her mind and her memory, although he courts her gently.

Wanyu becomes Zhang’s instrument for effecting forgiveness and starting anew, but the film never suggests that recovery of what was lost and damaged in the course of China’s upheaval is possible. At one point, discovering a previously undetected sacrifice on his wife’s part, Wanyu seeks redress but finds culpability buried under successive layers of political change. His only recourse is to walk away from someone now on the wrong side of history, as he once was himself. Zhang Yimou’s final shot of the film is bittersweet in its acknowledgement that looking forward is the only option.