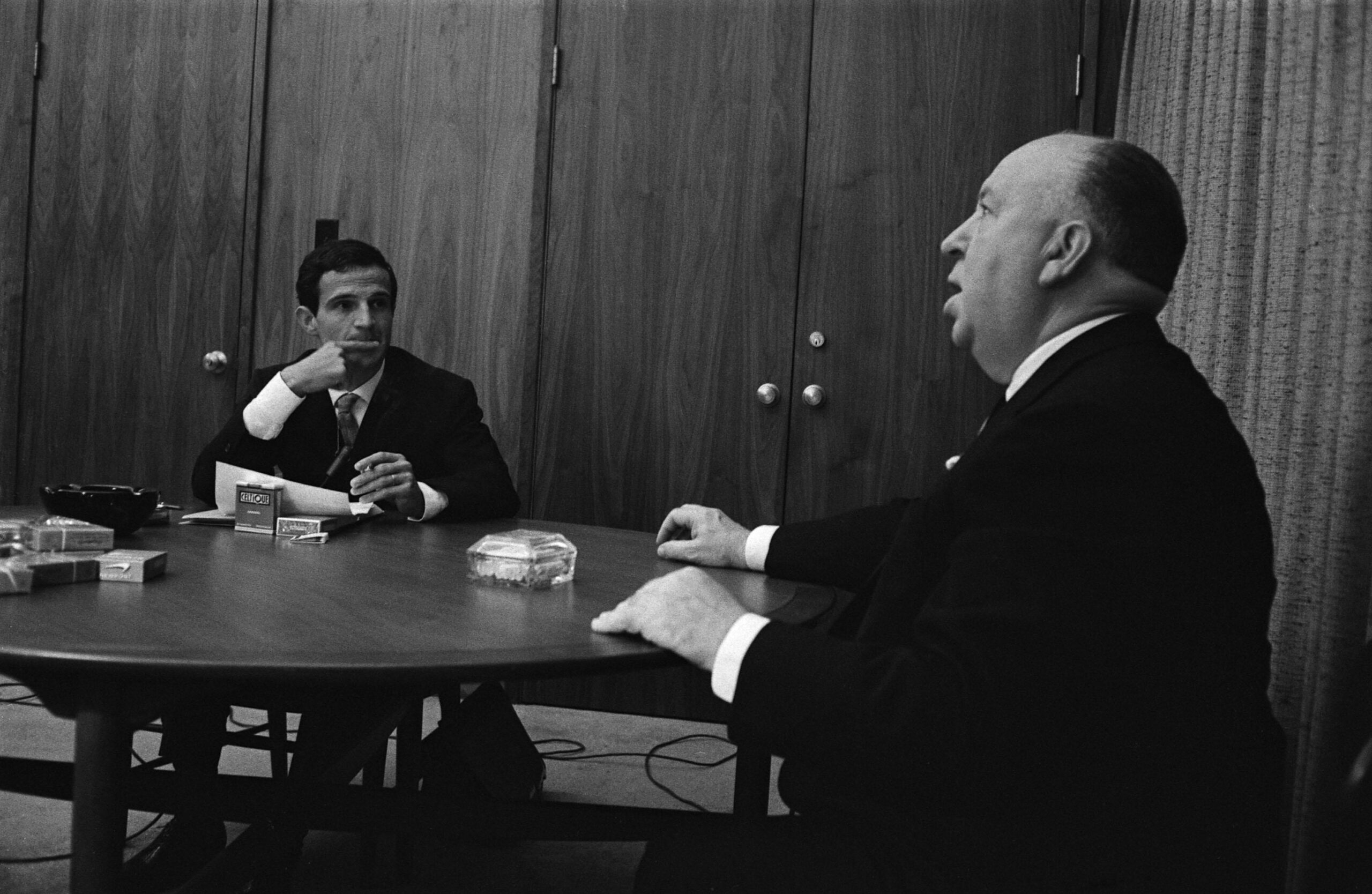

All cinephiles worth their salt have spent hours upon hours poring over the works of Alfred Hitchcock. I’d wager that most of us also know every page of “Hitchcock/Truffaut,” the book adapted from the week of interviews that François Truffaut conducted with Hitchcock in 1966. Kent Jones’s documentary of the same name makes the case for the book as one of Truffaut’s—and Hitchcock’s—great works, a text that had an impact worthy of one of their movies. (Disclosure: I know Jones, who runs the New York Film Festival.)

The pleasure of this fluid and engaging film, shown in Cannes Classics, is that it isn’t simply a rundown of key points from the book, although it does cover some of the same ground (the definition of suspense, the way in which actors should be treated like cattle, the notion that “logic is dull”). Rather, the documentary uses film clips, audio from the interviews, and fresh insights to augment a text that, as the interviewees note, discusses filmmaking in unusually plainspoken and direct terms. Contemporary directors speak of the impact that the book had on them before they started making movies and share their own ideas about Hitchcock’s work. David Fincher discusses Hitchcock’s genius with the fundamentals of moviemaking—his use of space; the way he sped up and slowed down action. Martin Scorsese highlights details that I’d never considered before, such as the importance of finding the perfect height for the steering wheel in Janet Leigh’s driving scenes in “Psycho.”

Like the book, “Hitchcock/Truffaut” is a work of annotation par excellence, with in-depth examinations of scenes in “The Birds,” “Vertigo,” and “The Wrong Man.” The movie is even illuminating on more mundane matters, such as the way Hitchcock staged some of the famous photographs that Philippe Halsman took of him and Truffaut. The subject matter is irresistible, but Jones laces it with a sly critical statement. The movie offers an implicit defense of later works like “Topaz,” perhaps in answer to a question that Hitchcock asked of himself: Had he been adventurous enough? Had he become a prisoner of his own form?

One Cannes film with a premise that Hitchcock might have appreciated is Jeremy Saulnier’s “Green Room,” shown in Directors’ Fortnight, where Saulnier’s “Blue Ruin” played in 2013. Again, per Hitchcock, logic need not apply. The film involves a cash-strapped band that books a gig playing at a bar that has a clientele of white supremacists. As the band members (the actors include Anton Yelchin and Alia Shawkat) leave, they discover a murder in the green room. Now witnesses, they are quickly entrapped there.

Owing more to John Carpenter’s “Assault on Precinct 13” than to Hitchcock’s “Rear Window,” the movie proceeds to put them in a standoff with the white-power movement’s leader (an out-there performance by Patrick Stewart); there are negotiations over guns, trust, and exit strategy. Some of the dialogue was muffled, to an extent that a critic colleague and I wondered whether it was an artistic choice or a problem with the sound. But that mattered less than you might think. “Hitchcock/Truffaut” highlights the influence of silent filmmaking throughout Hitchcock’s career, and if Saulnier’s movie is an eye-roller on a screenplay level, it delivers the goods in visual and visceral terms, with a lot of gory injuries and escalating nastiness.

Apropos of that: Last night I attended the midnight premiere of Gaspar Noé’s “Love.” Having seen a long cut of “Enter the Void” at the Grand Theatre Lumière here in 2009—I’ll never forget the moment when, after a lengthy cut to black, a giant penis started thrusting toward the audience—the idea of Noé working on a 3-D hardcore feature was a terrifying prospect.

But when it comes “Love,” nothing had prepared me for so much…dialogue. Hardcore movies are not exactly known for their thespian excellence, but the movie’s endless chatter and (initially) pervasive voiceover inspire not so much arousal as a desire to plug your ears. Whether the characters are pretentiously brandishing their cultural bona fides (“You’ve never seen ‘2001’?”) or speaking with an awkward cadence (“Did You Ever. Try Sex. On Opium? It’s very. Chill”) that probably needed to be ironed out with a few more takes, there’s nothing about “Love” that a sound malfunction—or perhaps silent-film intertitles—wouldn’t improve. The scene in which the American protagonist attempts to explain his victimization to a French cop brought down the house.

Oh, and yes, the movie has lots and lots of arty sex, including an inevitable money shot that would have one-upped “Enter the Void” had “A Very Harold & Kumar 3D Christmas” not gotten there first. Centering on the relationship between an aspiring filmmaker, Murphy (Karl Glusman), and an artist, the portentously named Electra (Aomi Muyock), as well as their (intermittently forgotten?) menage à trois with a third woman (Klara Kristin), “Love” has an almost clumsily self-baring quality. (There’s a discussion of naming a baby Gaspar, and the dramatis personae include a gallery owner named Noé who looks quite a bit like the director.) Lest we miss the movie’s message, Murphy expresses a desire to depict “sentimental sexuality” in his own films.

On this point, it seems churlish to doubt Noé’s sincerity. Indeed, like “Last Tango in Paris,” the film is haunted by the specter of a suicide. Noé signals his incendiary ambitions by littering his frames with posters for “Salò” and “The Birth of a Nation” (!). But “Love” is one film in which performance decidedly does not measure up to ambition.