Of all the criticisms that are leveled at David Lynch, perhaps the most persistent is that you simply can’t “get” his movies, that there’s no coherent through-line, that each scene out-“WTF’s” the other. This is true, to a certain extent: there is no American director more in touch with the human subconscious than Lynch, no one who reaches more deeply into the imagination for imagery and symbology. Wacky he is, in spades. And “Mulholland Dr.,” a discombobulating tale of two actresses searching for their identities in different ways in Hollywood, newly released in Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection, does little to chip away at this reputation. And yet, times two: how firmly grounded is this reputation? And, why is it that we say we can’t “understand” his work?

There’s a lot to chew on in the new Criterion release: personable interviews with stars Naomi Watts, Elena Harring, and Theroux, as well as Lynch himself, soundtrack composer Angelo Badalamenti, and others. But the material here that may be most pertinent is found in an interview with Lynch by Chris Rodley provided in the booklet. Lynch says of the film, “I think [audiences] really know for themselves what it’s about. I think that intuition—the detective in us—puts things together in a way that makes sense for us … [p]oets can catch an abstraction in words and give you a feeling that you can’t get any other way.”

And that’s just it: grasping this film has to be intuitive; it has to be read the way a poem is read. There will be gaps in the information provided, and significant ones: it is the viewer’s large job to fill them in.

Near the end of the interview, Lynch alludes to the Surrealist poets, and their seemingly randomized way of associating words and images; while it goes without saying that Lynch wears the Surrealists’ influence on his sleeve, the difference between them is crucial. The Surrealists savored the explosion that took place when disparate ideas met; Lynch savors it too, but only insofar as it serves a larger story he is trying to tell. And if the story told is that of a story falling apart, then so be it. When watching “Mulholland Dr.,” then, viewers’ enjoyment is decided not by the film itself but by the degree to which they can let it, as William Carlos Williams once said of the modern poem, “spray in your face.” And this is where Lynch has gotten into trouble with his critics. Rather than accepting that a film might build itself on poetic logic, they expect novelistic logic—and when that kind of logic is absent, the film gets responses like Stephen Holden’s claim that Lynch is “surrendering any semblance of rationality” or J. Hoberman’s naming of the film “thrilling and ludicrous … entirely instinctual.”

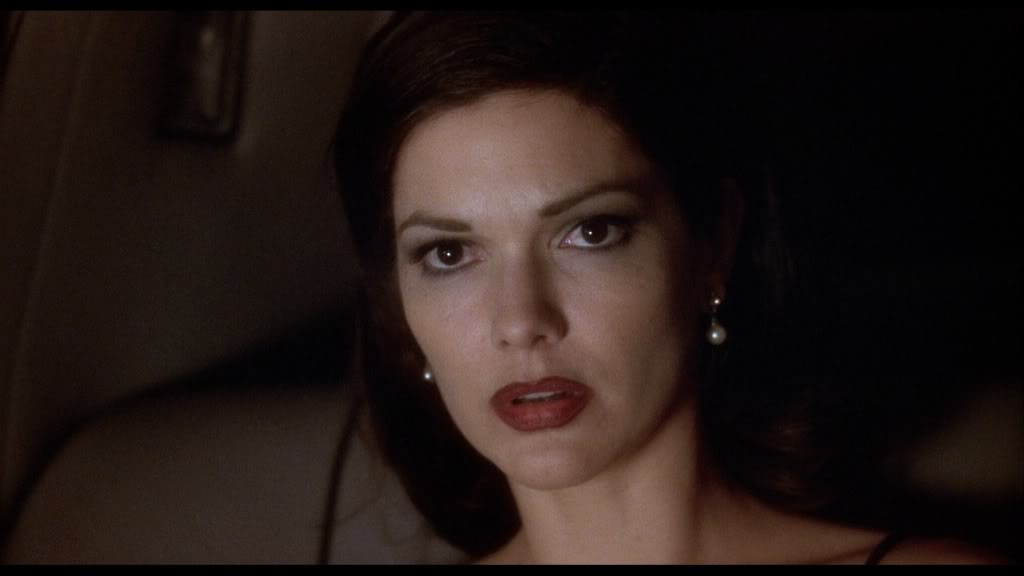

If one views the film as a poem, on the other hand, and then takes its plot events as symbolic machinations, its seemingly absurd moments give way easily when prodded for significance. Let’s take a few examples. How about the opening? We see men and women in 1950s clothes, swinging each other around wildly to clamorous music, and then Betty’s (Watts) smiling, beatific face. Then we cut to a dark road, Mulholland Drive, in fact; Rita (Elena Harring) sits in a darkened car. In a few moments, a car crash will take place which sets the events of the movie in motion. But what do these two scenes have to do with each other?

Well, two things, at least. Lynch is setting a mood with this juxtaposition, a mood of imbalance in which the story he wants to tell, that of a young woman losing her sense of self as she pursues dreams of being a movie star, can be told. Additionally, as we find out late in the film, Betty won a dance contest, which is the reason why, very shortly after the car crash, we see her arrive in California, fresh and naïve (sort of). Lynch has put all the parts in place; he just wants us to figure out how they relate.

To take another example, how do we explain the monster behind Winkie’s Diner, who kills a young man just by looking at him? This figure is a representative of pure fear and precariousness itself, which would seem to be what drives the Hollywood movie industry, at least in Lynch’s vision of it. Though the scenes we find here of the movie business in action are passed over fairly quickly, their stakes are high. Will Justin Theroux’s cuckolded film director find credibility and be allowed to make the movie he wishes to make? It doesn’t seem likely; he knows it and we know it. Will Betty make it as an actress? No, she doesn’t, and the difference between “making it” and “not making it” is enormous, in terms of the effect it has on her character; the fresh-faced and unpredictable Betty we see early in the film is replaced by a careworn, exhausted version of herself later. All of the characters in the film must face their own version of the monster behind Winkie’s.

And what of Rebekah Del Rio’s performance of “Llorando”? In one sense, it seems an inexplicable flight of fancy on Lynch’s part, a descent into self-indulgence. Viewed symbolically, though, it seems entirely reasonable. The portentous phrase “No hay banda” becomes an indication of the nakedness of performance or of life, in which we are all lip-synching, like Del Rio, a song into which we pour all our emotion—and if we collapse, human existence goes on. (Goes on singing, if you wish.) Rita and Betty cry as they watch for any number of reasons: their burgeoning attraction, their longing for stardom, their witness of its cost in Del Rio’s face. Symbolism 101.

A possible concern with the explanations above, of course, is that they don’t tell the whole story. Why the nearly empty theater for the “Llorando” performance? Why does the man behind Winkie’s have a vaguely witchlike appearance? Also, why there? And why, in the film’s opening scene, are all of the dancing figures dressed as if they’ve been dropped into the film from the 1950s? There is both an answer to this question and no answer whatsoever—and the two options are, interestingly enough, linked. Within any artistic work, there will be a certain number of decisions which are made for the sake of the work and whose connection to the work’s frame is not entirely clear on first interrogation. Or second. Or third. And asking the artist, unfortunately, is ultimately no help, for the ultimate answer will always be, “Because it was the right decision for the work.”

What has happened in Lynch’s work, as time has passed, is that there is an increasing plenitude of such moments, sometimes such a plenitude that they seem like the point of the film. And perhaps they are. One of Lynch’s earliest films of note, “The Elephant Man,” was based on a play; “Dune” and “Wild at Heart” were based on novels. There was a point in Lynch’s development, clearly, where he felt the lure of adaptation, of bringing an author’s narrative vision to life in a way which he could make his own. But in recent years, as he has increased his vice-like creative grip on his work, we’ve seen him take those narratives apart, to see how they work. He lays them on the table in front of us. We see the parts. And, floating above them, there is the madness which caused the narrative to be created in the first place. This is what Lynch, with his characteristic enthusiasm, wants us to look at—and moreover, he wants us to understand its peculiar logic. This kind of madness is, after all, what shapes entire cultures.