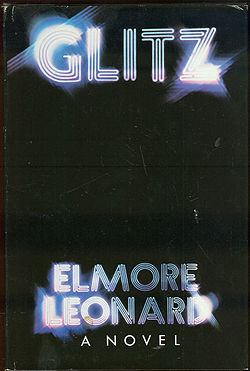

The first rule in Elmore Leonard‘s ten rules of writing is “Never open a book with the weather.” It could never be a “dark and stormy night” in Leonard’s universe. Instead, he opened his novels with nonchalant statements of character-driven fact. “Rum Punch” begins “Sunday morning, Ordell took Louis to watch the white-power demonstration in downtown Palm Beach.” “The Hot Kid” informs us that “Carlos Webster was fifteen the day he witnessed the robbery and killing at Deering’s drugstore.” And “Glitz”‘s opening line kicks off two and a half of Leonard’s most readable pages with “The night Vincent was shot he saw it coming.”

Elmore Leonard got straight to the point. His characters were sometimes in love with their verbosity, but Leonard the narrator did not share this predilection. The omnipotent voice running through Dutch Leonard’s work told you who said what, who did what, and the darkly comic repercussions of both. No writer wrung more color out of simply telling you what happened than Dutch Leonard.

“Melanie was holding it in both hands now, arms extended, aimed at Gerald.

“He tossed the shotgun to land on the sofa, looked up at Melanie and said ‘Okay, now you put that down, honey, and I won’t press charges against you.’ Confident about it, as though it would settle the matter.

“Melanie didn’t say anything. She shot him.” –”Rum Punch”

Leonard’s characters were a multi-racial motley crew of cops, criminals, outlaws, lawyers, cowboys and sociopaths. They did not always follow the crime fiction novel’s gender conventions. Strong, brutal women and weak, emotional men were not verboten. Leonard’s characters were beholden to their own self-defined notions of ethics and morality. They were often much less clever than they thought; their flaws of nemesis underestimation became their undoing. Those who survived sometimes found themselves in other novels. Leonard never passed judgment as his characters flamed out in pitch black comic blazes both pathetic and glorious. To do so would violate his last and most important rule of writing: “Leave out the parts readers tend to skip.”

Much of the pleasure of reading Elmore Leonard was in the dialogue, which is why so many of his books became movies and TV series. Leonard followed his rule of “avoiding detailed descriptions of characters” by having his people talk to each other. He had an ear for the way conversations flowed, whether they were conducted on the street, in the precinct, or on the range. For a White guy, he certainly knew how to sound convincingly like the Black dudes who populated many of his novels. He captured the cadences of their speech, and did so without stereotype. His Brothers sounded like the guys I heard on the street in my old neighborhood; his cops sounded like cops I knew. Leonard embraced and elevated what they said, letting them ramble on whenever necessary. This love of casual chatter is probably what drew Tarantino to adapt “Rum Punch” as “Jackie Brown.” It’s certainly what made him pull entire chunks of Leonard’s dialogue verbatim into the “Jackie Brown” script.

The labyrinthine plots Leonard dragged his characters through were overly complicated yet always compelling. Even in something as spare and nasty as “52 Pick-Up,” the first book of his I read, Leonard toyed with the expectations of where his stories took us. Even in the most convoluted plots, there was a feeling that the reader got entangled in this mess by virtue of the characters’ machinations, not the author’s.

Before turning to the Florida-set crime stories that became his trademark, Elmore Leonard wrote Westerns. “3:10 to Yuma” and “The Tall T” were based on his work, as was Paul Newman’s 1967 film “Hombre.” Starting with “The Big Bounce” (made with Ryan O'Neal in 1969), Leonard changed his genre but kept many of the characteristics of a good Western. For example, “Mr. Majestyk” features a character protecting his “homestead” in much the same way as Jimmy Stewart or Randolph Scott would have. And of course, “Justified”‘s Raylan Givens is the perfect synthesis of both genre halves of Leonard’s work.

Is there another author besides Shakespeare and Stephen King whose prolific output inspired so many movie adaptations? And by directors as varied as Abel Ferrara, Steven Soderbergh, Quentin Tarantino, Budd Boetticher, John Frankenheimer, Barry Sonnenfeld and Burt Reynolds (whom I’m sure Leonard wanted to shoot after seeing “Stick”). The stories vary from tales of Hollywood to big money heists to sleazy exploitation. Regardless of quality—and it varied from film to film—the spirit of Dutch Leonard’s prose was felt by the viewer.

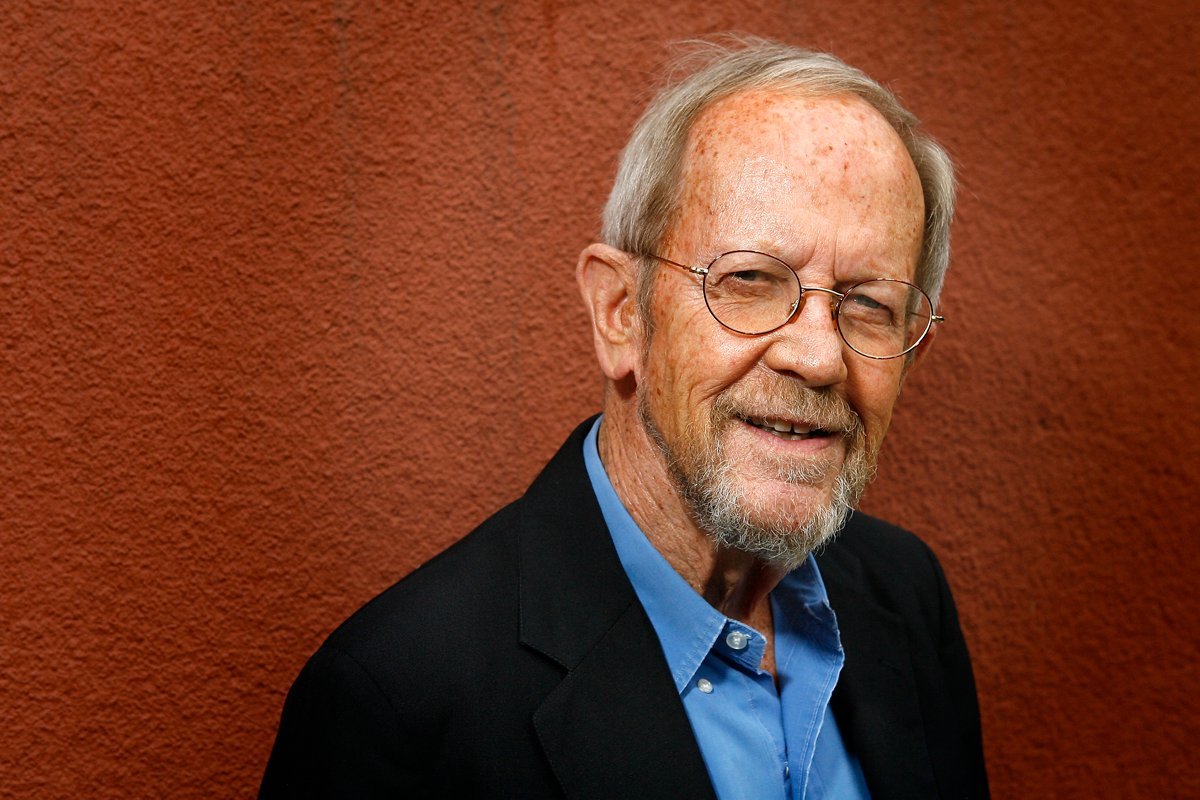

Since I was 17, Elmore Leonard has been my favorite writer. I told him so the one time I met him. It was at the now defunct and long-gone Waldenbooks on Exchange Place and Broadway in Manhattan. He was there to sign copies of “Rum Punch,” which was eerily prescient since it was the basis of my favorite film adaptation of Leonard’s work. He was a very nice man, patiently listening to the 22-year-old aspiring writer whose excited rambling violated Leonard’s fourth rule of writing (“Keep your exclamation points under control!”). When I was done, he verified the spelling of my name, signed my book and wished me luck with my writing.

Since I was 17, Elmore Leonard has been my favorite writer. I told him so the one time I met him. It was at the now defunct and long-gone Waldenbooks on Exchange Place and Broadway in Manhattan. He was there to sign copies of “Rum Punch,” which was eerily prescient since it was the basis of my favorite film adaptation of Leonard’s work. He was a very nice man, patiently listening to the 22-year-old aspiring writer whose excited rambling violated Leonard’s fourth rule of writing (“Keep your exclamation points under control!”). When I was done, he verified the spelling of my name, signed my book and wished me luck with my writing.

I hadn’t thought about that meeting in a while, but when I heard that Leonard died today, it rushed back to me with the immersive force of a good Elmore Leonard set piece. There was casual chatter, a cool as a cucumber experienced character, and a matter of fact, straightforward rendering of events. Nobody got shot, which is a good thing for me, but that didn’t make my run-in with Mr. Leonard any less memorable.

Rest in peace, Dutch.