Still in shock over

the death

of Prince at the age of 57, we asked the staff of RogerEbert.com to share

some thoughts on his music, movie, influence and whatever else they wanted to

share. We also thought we’d include some of our favorite responses from social

media yesterday, capturing a world in mourning but also celebrating the

importance of the man who called himself Prince.

BRIAN TALLERICO

All day, I’ve been trying to figure out what to say to

capture what Prince meant to me. As cheesy as it sounds, his impact on my

musical taste goes beyond words. But I’ll try. To be honest, as we personalize

everything, Prince’s passing makes me feel old. His music was the soundtrack of

my youth. While I’m sure he recorded great stuff in the ‘00s and ‘10s, I

remember him as an icon of my upbringing. From controversial videos like “When

Doves Cry” when I was kid (which always felt like a video I shouldn’t be watching)

to the fact that I wore out my tape of the “Batman” soundtrack, he was always

there in the ‘80s. He tapped into something my adolescent brain couldn’t

understand at the time, but I always just

knew Prince was cool.

Babies know Prince is cool. Old people know Prince is cool. Non-English speakers know

Prince is cool.

And then the ‘90s came around and I started to appreciate Prince more

artistically—a brilliant lyrical turn of phrase, the guitar playing on “Purple

Rain,” his groundbreaking sexuality, ALL of “Sign O’ the Times,” etc.

But my

strongest correlation with Prince is dancing. In college, I became the guy who

ended up in charge of the music at most of the parties we threw. I had the

right pop music taste, I guess. There were songs that came out regularly every

time I was in charge of the CD player, but the song I played more than

any other had to be “Let’s Go Crazy,” a perfect dance song (“Raspberry Beret”

and “7” may have been #2 and #3 if I’m being honest). We ruined CDs of Prince’s

greatest hits.

When I think of Prince, I picture my friends in

college, smiling and dancing like there are no worries and no tomorrow. “Dearly

beloved…” rings out and everyone hits

the dance floor. And for those three minutes, nothing else matters but the

moment. We are forever young in that memory, always happy, always dancing,

always smiling. And Prince is always cool.

GLENN KENNY

Because the world didn’t stop after Prince’s death, I was

obliged to bring his music with me on the day of his death, and listening to

“June,” the final track from one of his most recent albums, “Hit N Run Phase

One,” I was struck by a couplet that I now see was noted by a bunch of

reviewers on the album’s release: “I was born much too late/I should have been

born on the Woodstock stage.” Prince was 57, a year older than myself. I wasn’t

able to go to Woodstock because I was ten, and my parents weren’t hippies; I

presume he wasn’t able to go because he was eleven, and lived in Minneapolis. I

don’t think his parents were hippies either.

But as the world recollects the

sexy, impertinent Prince, my image of Prince is more and more tinged by his

utopian aspirations, aspirations that in his timeline and sensibility go

straight back to Woodstock, and to the idealism and intelligence of, say, one

of the artists he most revered, Joni Mitchell. Revisiting the provocation of

“Dirty Mind” I was blown away by his sequencing of the record: he kicks off

with the title track, a compressed falsetto driven raver that’s nonetheless

kind of contained (its lyrics aren’t as lubricious as the title suggests). He

then drops one of the greatest and knottiest pop songs ever written, “When You

Were Mine,” like it just occurred to him. The record builds in outrageousness;

on the side two opener, “Uptown,” the observation “Black, white, Puerto

Rican/Everybody’s just a freakin’” mainly sounds chantable, and he follows the

song with two of his most outrageous sex scenes, “Head” and the incest-praising

kidding-on-the-square “Sister.” The album closer “Party Up” feels like a call to

just start the record over again, and at dance parties in the early ‘80s that’s

just what they’d do. But it’s also an anti-draft song, calling for “rock and

roll revolution,” and its protest message gets stronger as the song builds,

sliding into a chant of “You’re gonna have to fight your own damn war/cause we

don’t wanna fight no more.”

Now the draft in the United States had ended in

1973—back when I was 14 and Prince was 15. HOWEVER. Registration for the draft was reinstated in

July of 1980—by Jimmy Carter, no less. How on point was Prince as a protest

singer? “Dirty Mind” was released in October of 1980.

And he didn’t stop. “We

are the new power generation/we want to change the world/the only thing that’s

in our way is you,” he sang in 1990, on the soundtrack to a movie that’s kind

of an unholy post-hippie mess, “Graffiti Bridge.” I have a lot of affection for

that picture in spite of its ineptitude, because it’s Prince’s hazy attempt at

conjuring a counterculture out of his persona. An awkward proclamation, from

behind all the corkscrews his persona could throw up and throw out, that he

really did think somehow that love is the answer.

SUSAN WLOSZCZYNA

I was first introduced to the magnetic powers of Prince

while working in the features department at the Niagara Gazette in Niagara

Falls, N.Y. We often received review copies of albums that we would share with

the staff once we were done with them. One day, his second record—simply titled

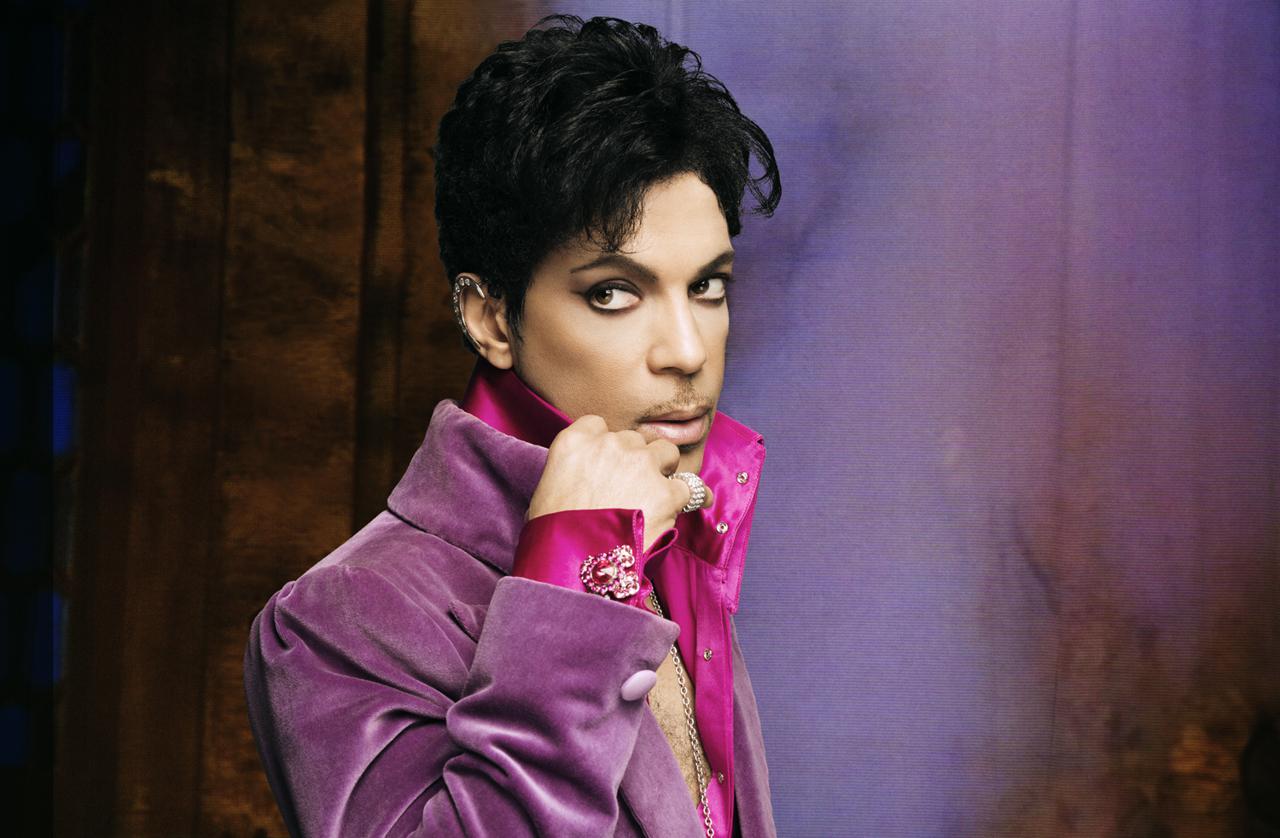

“Prince”—arrived in the mail. There he

was on the cover, brazenly staring forth with libidinous intent while sporting

only a corona of dark hair fit for a gothic-romance hero and a bare chest

flecked with come-hither curls.

The record practically melted in my hands.

Suddenly, I looked up and saw our normally well-mannered editorial assistant

Annie Hicks hovering over me and shaking with excitement. I was too afraid not

to give it to her. Later, when I worked the copy desk at USA TODAY in the early

‘80s, I often gazed up at a monitor tuned to MTV whenever Prince crawled out of

that smoky bathtub while singing “While Doves Cry.” Thank goodness that clip

from “Purple Rain” played about 20 times a day.

While I appreciated his music—especially

the heart-wrenching “Nothing Compares 2 U” and the innuendo-laden “Little Red

Corvette” —I can’t say I was the biggest fan of his forays into movies. But his

visually alluring videos regularly provided the perfect quickie pick-me-up, a

sublime hot-stuff alternative to mere workplace coffee. I probably would never have survived so long

in journalism without him.

JANA MONJI

Just an hour ago, I was searching for it, thinking it was in my cedar chest, but finding it in a watermelon-themed basket that I had once used as part of a prize-winning costume to portray melon + collie. I had thought about my raspberry beret earlier this month, thinking I would take it with me to Ebertfest, but decided against it. I bought the beret on a whim, from a store that no longer exists in a city where I no longer live.

I was dressed head-to-toe in purple when I read the news of his death, running between classes. In the evening, I drove through Los Angeles traffic to a festival opening where the organizers mentioned Prince in their opening remarks, and after the movie, they played his music. The tent housing the after-party was too crowded; no one was dancing.

I’m one of those people who doesn’t need liquor to get me out on the dance floor. I think I can remember flashes of what I was wearing when I was dancing to “Let’s Go Crazy” in a time before swing and tango turned my world around. By then, I had joined a legion of purple-loving people, proud to be a member of a kingdom led by a doe-eyed Prince. When I first saw “Purple Rain,” I was excited by Prince’s electric stage presence and his dance moves. The promise made by “Purple Rain” went unfulfilled when Prince took control and directed himself in movies like “Under the Cherry Moon.” I would have totally loved to wear those long frock coats and frilly shirts he sported in either movie. In another era, he would have been called a dandy. In today’s world of Cosplay and Steampunk, his costumes would still be fashionable. Thanks to MTV and music videos, Prince will live on forever young.

Thanks to YouTube, you can see dance videos where dance lovers compare his moves to other fine dancing men–James Brown and Michael Jackson. Just remember, Prince often danced in high heeled shoes that Ginger Rogers might have once worn. Just remember, his generosity that allowed a Chicago-based ballet company, Joffrey, to raid his catalog to choreograph “Billboards,” and he waived the royalty fees. Just remember, he once played a Super Bowl halftime show during a torrential downpour. Just remember, his genius and tragic life when you wear your raspberry beret or purple best. He built his mythology and it lives on. Good night, sweet Prince of Purple.

PETER SOBCZYNSKI

I just finished writing nearly 1000 words about Prince and

his contributions to the world of film on the occasion of his untimely passing

and before beginning this sentence, I deleted every single one of them on the

basis that they did not even come close to explaining the man, his creative

output, and my deep and unwavering admiration for both. In my defense, I could

write ten times that amount and still barely begin to scratch the surface in

that regard.

As a musical talent, he was literally without peer—a multitalented

prodigy who absorbed the influences of James Brown, The Beatles and Jimi

Hendrix and transformed them into something so unique that they would

revolutionize the pop music landscape and influence countless others over the

years. In 1984, he made his big screen debut in “Purple Rain.” Whatever the

flaws of that particular film, the combination of his unique and

overtly sexual screen charisma and the knockout soundtrack that he composed

(including such classics as “When Doves Cry,” “Let’s Go Crazy” and the majestic

title tune) proved to be irresistible, and it into a critical and commercial smash that turned him into one of the biggest stars in the world

and the winner of the last Oscar to date given out for Original Song Score—even

the squares at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences could not deny him in that case.

His other film

endeavors—the weirdo romantic gigolo drama “Under the Cherry Moon” (1986), the

straight-up concert film “Sign ‘o’ the Times” (1987) and the quasi-“Purple

Rain” sequel “Graffiti Bridge” (1990), all of which he directed—did not

come close to approximating the seismic impact of that first film, but all of them are

more interesting and ambitious than the typical vanity production made by a

singer trying for screen stardom. And the soundtracks are, of course, killer.

Now he is gone and even though the Grim Reaper has been

especially busy this year, this is a passing that really hurts. While there was

a time when his albums began to grow unwieldy—thanks to the extra time

provided by CDs, he began stuffing his releases that might have otherwise been

left behind to make for a more cohesive album—but his recent releases had

demonstrated a new focus, and his live performances—ranging from his epic

concert performances to his now-legendary Super Bowl halftime performance (arguably

the best one in the history of the game)—thrilled audiences around the world. He was reportedly working on his autobiography, and there were constant rumors

of a super-deluxe reissue of the “Purple Rain” album and of a vault jam-packed

with countless unreleased tunes—a thrill, considering that his discards are

usually better than the greatest hits of most other performers. Whether any of

these items ever see the light of day remains to be seen but even if they

remain under lock and key, we are still left with the astonishing results of

one of the most fruitful artistic careers of our time. As someone who once

actually made the pilgrimage to his fabled Paisley Park recording studio in

Minnesota, I can assure you that he will be missed and revered in equal

measure.

COLLIN SOUTER

I remember being 12 years old and hearing and seeing

“Purple Rain” for the first time and never quite getting it out of my

system. At the time, for me, it was the first album since “Sgt.

Pepper” that I remember being a beginning-to-end perfect album, that it

had to be listened to in its entirety in one sitting. I’m pretty sure I saw the

movie first, though, after already seeing the videos for “When Doves

Cry” and “Let’s Go Crazy.” I was very much drawn to the

imaginative images of androgyny and decadence as well as the music and grew

more and more curious about the film. It felt like a Rated-R event film at the

time. My mom must have been just as curious, because she actually took me to

see it. I was way too young for it, but I loved it anyway and watched it

repeatedly when it came out on video. And that vinyl copy of “Purple

Rain” still exists in my record collection.

His career had many peaks and valleys, but he was always one

of the most fearless voices in music. Even with something as commercially

successful as “Purple Rain,” he made his character out to be a truly

unlikable sonofabitch, a real anti-hero at a time when such a concept in

mainstream cinema was unfashionable. I don’t have much to say about his

follow-up features “Under the Cherry Moon” or “Graffiti

Bridge,” but his final cinematic outing, the currently out-of-print concert

film “Sign O' the Times,” deserves to be made available once again.

Like, now. A true original, he will be sorely missed.

SIMON ABRAMS

After George Clinton, Prince was the funkiest man alive.

That’s a testament to an enduring legacy that’s only slightly been tarnished by

our collective neglect of his recent work. Too many of us—including this writer—took

the big stuff for granted, because there was so much of it (“1999” or “Purple

Rain” soundtrack? Why not “Sign O’ The Times”?). And so many sniffed

at/defended the little stuff, though some were more eloquent in this particular

arena than others (you should hear Odie Henderson defend “The Black Album”).

But this was Prince! The star you couldn’t interview without taking mental

notes (no recordings, please). The diva that we all swooned over despite his

ridiculous name change (Don’t even). The god that survived “Under the Cherry

Moon”! Is it just me, or did we let the His Funkiness down by not paying

enough attention?

KATHERINE TULICH

As a rookie music and film reviewer at the Sydney Morning Herald in 1984, being assigned to review this “small” music film “Purple Rain” seemed like the perfect assignment for the straight out of college kid in the office. Well, I was mesmerized. It wasn’t a concert film, and in this nascent era of MTV it wasn’t a string of music videos to support an album. Prince had achieve something groundbreaking: a part-autobiographical story of a tortured, rising musician with a mesmerizing soundtrack. He may have not been a great actor, but you could not take your eyes off him. His contemporary rival at the time, Michael Jackson’s venture into film was a lightweight musical (1978’s “The Wiz“), but Prince stayed true to his musical genius and integrity. My editor couldn’t believe I gave what he saw as a trivial film a glowing review but It began for me a lifelong passion (not only for the color purple) but seeking out any opportunity to grasp a new vinyl/CD of anything Prince related (including such musical proteges as Sheila E and Vanity 6). I even traveled to the US to see his legendary “Purple Rain” tour. While he never captured the same onscreen persona in later embarrassingly forgettable films, onstage the diminutive singer loomed large and I was so privileged to see him many times on stage. Nothing compares to Prince.

OMER MOZAFFAR

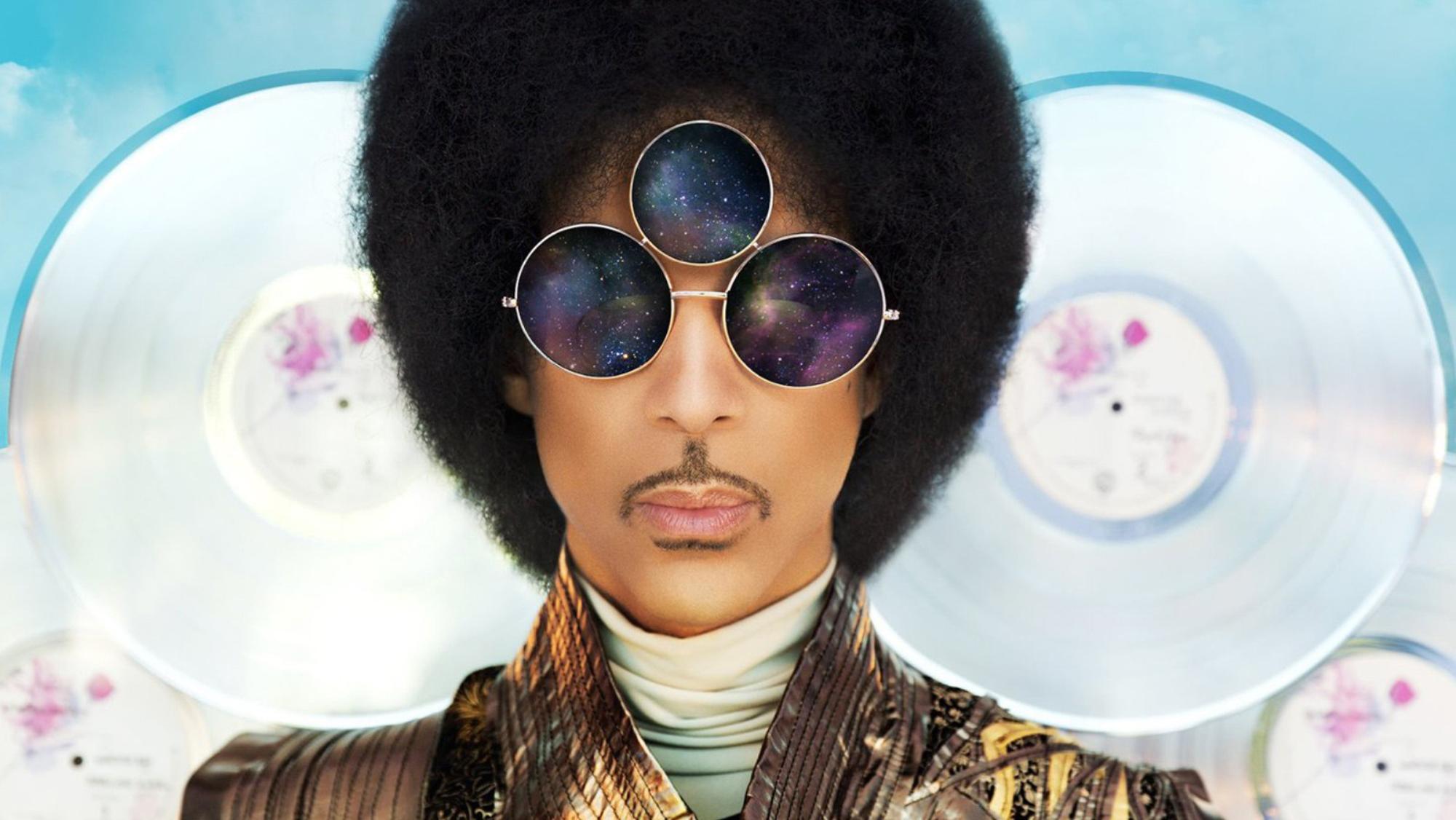

Other performers of his generation would dress in different

costumes, reinventing themselves like clowns changing their makeup. When Prince

took on a new personality it seemed wholly authentic, wholly Prince, even when

it was not “Prince.” Rather than reach out to you, he was that artist

who brought you into his world, into his mind and body. When such artists embody their own souls,

they make some of us voyeurs and they make some of us free, free from the strictures

that prevent us from embodying our own selves.

OLIVIA COLLETTE

I can’t put sentences together about this, so here’s me, not

trying:

Purple swashbuckler

Pegasus rider

Movie goer, movie star

Movie music man

Batman music man

Multi-instrumentalist

Mental instrumentalist

Jazz Mephisto

Great sophisto

Peculiar, spectacular

Polemic, anthemic

And we weep for that unpronounceable love

MATT ZOLLER SEITZ

I first started seriously listening to Prince in 1984, when the album

and film “Purple Rain” came out and made him a superstar, while attending an

arts high school in Dallas, Texas. The Booker T. Washington High School for

Performing and Visual Arts did not have a sports team. Its symbol was the

Pegasus. But it could have been Prince.

This country is much more enlightened about

race, gender and sexual orientation now (though of course, the degree of

progress varies depending on who and where you are) so it’s tough for people

who weren’t alive to imagine how new and dangerous he was 32 years ago. My high school’s student body was a pretty even

mix of black, white and Latino students. I knew students who were gay or bisexual, straight girls who dressed a bit

butch and straight guys who dressed a bit femme, and a few cross-dressers, one of whom would go on to transition from female

to male after college. We all understood, on some deep and mysterious level, that he

spoke for the future, when a scenario like the one at our school would seem boringly typical.

His band was called The Revolution—proof that he knew what he was doing and what it meant to his listeners. He put his art

where his philosophy was. He fronted a rotating, racially and ethnically

diverse crew of men and women. He sang about God and sex, often in the same

song. He teased the audience’s perceptions of what it meant to be male or

female by wearing makeup and high-heeled boots and

clothes with ruffles and puffy sleeves. He wrote out his lyrics with numbers in

place of prepositions. He insisted that it didn’t matter why you did or

didn’t find him attractive or what label you tried to hang on him because he

was his own person.

Musically, he was a one-man record store,

an aesthetic quilt of influences: gospel, Motown, hard funk, bubblegum pop, and

scorching rock-and-roll (his Jimi Hendrix-level guitar solos were so high

energy they could have powered a small country). I suspect his impact on

teenage consciousness in the ’80s was as seismic as David Bowie and Lou Reed’s

had been in the ‘70s, though surely with a wider reach. Like Michael Jackson, Prince was a unifier, an ’80s artist everyone

could

agree on, but more thrilling than Michael because he was so disreputable

and strange, sincere and defiant. He was somebody your parents could never approve of. His image, music and

public statements were so much more far-reaching, appealing to listeners of

every description. The white kids who were into heavy metal and

’70s arena rock respected him. The black kids who listened mostly to hip hop

and soul respected him. How could you not respect Prince? He did a hundred different things, and

did most of them better than anybody who’d spent their lives specializing in

just one thing.

Sometimes he overreached, but who cares? I don’t think he did, much. He built on his massive film debut

in Albert Magnoli’s “Purple Rain,” by directing his next three

films—”Under the Cherry Moon,” “Sign O’ the Times” and

“Graffiti Bridge”—himself. They all flopped. He didn’t seem hugely broken up over that. That he had failed to conquer one area of the arts meant he had to content himself with being the unquestioned ruler of a half-dozen others.

I bet a big part of his confidence came from knowing how awesome he was, that his genius wasn’t hype but verifiable fact. In collaborations, he carried himself as the equal of whoever he was partnering with, and he wasn’t wrong. He did music for Tim Burton’s

“Batman,” but most of it got cut out of the movie because it was just

too aggressively Prince-like. Whenever you hear it, the film suddenly turns

into a Prince video. Prince’s “Batdance” seems to suggest that he knows that what he’s doing is more fascinating than whatever the movie is trying to do. The video

opens with a Batman symbol filled by white noise (as if Prince is disrupting

Batman’s own logo—jamming his pop culture signal). Then the camera travels over

a phalanx of seated Batmen lit in Prince’s signature purple. Prince has already

turned the Caped Crusader into his own personal chorus line and we aren’t even

30 seconds in. Then the music and the dancing begin, and it’s as if Prince is

smashing past and present versions of Batman into pieces and merging them with

himself. He’s Batman and the Joker (or “Gemini” as he named

himself, after his astrological sign—creating his own Two-Face type character). He’s also Prince, performing

assorted instruments. There are Jokers, Batmen and Batgirls in the chorus,

crowing “Batmaaaaaan!!!!” in the manner of the campy 1960s TV

show that the movie, with its gloomy Expressionist visuals,

desperately wanted to supplant. (Prince has said that the theme to TV’s “Batman” was the first piece of music he taught himself to play on piano.) At one point Prince aims his guitar at a group

of dancing Batmen and seems to direct their actions, like a sorcerer making

brooms and mops dance by waving his magic wand.

Prince is one of the people most

responsible for warning labels on music—fallout from the sexually explicit

“Darling Nikki” on his “Purple Rain” soundtrack. It’s

hilarious in retrospect that the Powers that Be thought that such labels would

have a chilling effect on expression. After that, artists who wrote music that

was considered objectionable put out two versions, one edited and one raw. The

raw one had a sticker. Everybody wanted the sticker version. Nobody wanted the

safe version, except parents and Wal-Mart. Prince was like a creature from a 1950s science fiction

film: if you nuked him, it made him stronger. He got people used to the idea that

the sticker version of his music was the true version. This was not opportunism. It was a natural

outgrowth of his brand, which was integrity.

Prince was impressive enough at the

height of his popularity—roughly 1982 through about 1992, with a few zeitgeist

moments after that. But he became even more impressive during those periods

when he was trying to detach from the business apparatus that had once delivered

his music into the world. He was never more inspiring than when he was out

wandering in the pop culture winds, being mocked and dismissed while he labored

to remake himself on his terms, own his music, control his art, do what

he wanted without sucking up to middlemen or asking permission.

This was a musician who decided he would rather

replace his stage name with an unpronounceable symbol for several years running

than be associated with a record label, Warner Bros., that acted as if he was

their property. This was a musician who experimented with all manner of

alternate releasing strategies, including folding CDs of his music into

magazines and newspapers, because he

loathed how entertainment conglomerates treated artists, particularly

black artists, as resources to exploit.

From the moment he burst onto the scene

with his audaciously self-titled 1979 debut, he was always Prince, always

himself, or his selves, seemingly confident that sooner or later everybody

would have to acknowledge how amazing and special he was and pretend they were

always tuned into his wavelength.

They all got there.

On the evening of the day that Prince

died, I still had to run boring errands in my neighborhood. I had a beer in a

pub. I ate a slice at a pizzeria. I stopped into the pet store to buy

cat food. I bought socks, underwear and razor blades at a drugstore. I

stopped in a bodega on the way home and got a cup of coffee. Every single place

was playing Prince. I drank my beer while listening to “Lovesexy.”

The drugstore was playing “Cream” from “Dirty Mind.” The

counterman at the bodega was listening to “Purple Rain” on his

iPhone.

“What else have you listened to

today?” I asked him.

“Just this, mostly,” he said.

“I’ve got it on repeat.”

Prince remade the world in his image.

There should be a statue of him in front

of every arts high school in the world.

Purple, of course.