We’re happy to present an excerpt from Jason Bailey’s “The Ultimate Woody Allen Film Companion,” now available in stores and online. You can pick up a copy by clicking here.

Synopsis: A complete look at the extensive, ageless, unparalleled filmography of Woody Allen.

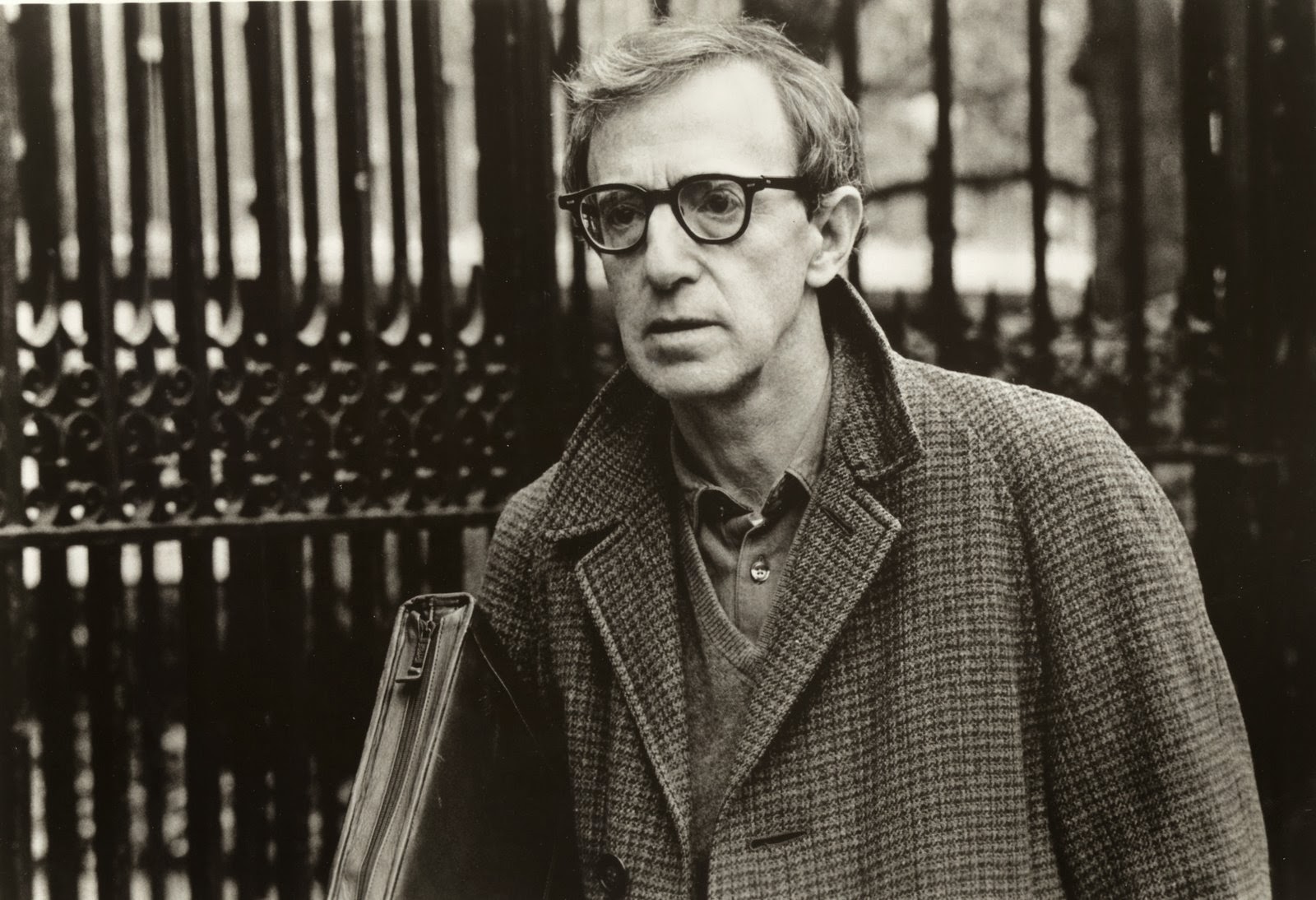

Writer, actor, director, comedian, author, and musician, Woody Allen is

one of the most culturally and cinematically influential filmmakers of

all time. His films – he has over 45 writing and directing credits to

his name – range from slapstick to tragedy, farce to fantasy. As one of

history’s most prolific moviemakers, his style and comic sensibility

have been imitated, but never replicated, by countless other filmmakers

over the years. In The Ultimate Woody Allen Film Companion, film writer Jason Bailey profiles every one of Allen’s films: from his debut feature, What’s Up, Tiger Lily, through slapstick classics such as Take the Money and Run and Sleeper; Academy Award-winning films such as Annie Hall and Hannah and Her Sisters; and recent gems such as Midnight in Paris and Blue Jasmine.

Bailey also includes essays on the fascinating themes that color

Allen’s works, from death and Freud to music and New York City. Getting

up close and personal with the actors and actresses that have brought

the iconic films to life, this book’s behind-the-scenes stories span the

entire career of a man whose catalog has grown into a timeless

cornerstone of American pop culture. Complete with full cast lists,

production details, and full-color images and artwork, The Ultimate Woody Allen Film Companion is the ultimate, indispensable reference to one of cinema’s most beloved and important figures.

“Woody“: Actor, Character, and

Persona

When Woody Allen started doing his nightclub

act, he quickly realized that there was more to being a performer than the

joke-machine writing he’d been doing since high school. Strong material wasn’t

hard to come by, and that’s why Catskills comics with socko gags were a dime a

dozen. The comics he idolized (Bob Hope, Groucho Marx, W. C. Fields, Jack

Benny) were about character first and jokes second. Once the audience knew and

understood the character, they would chuckle at even their weakest bits. To maximize

your laughs, you had to have a persona.

And from that realization, “Woody Allen” was

born. He wore thick-rimmed black glasses, the telltale accessory of a bookish

intellectual, a notion furthered by his frequent literary allusions and

surrealistic wordplay. Part and parcel for the comic intellectual, then, was

the presumption of physical weakness, the image of the meek, bullied nebbish,

an image further bolstered by the slight frame and thinning hair that made him

a combination of 98-pound weakling and red-headed stepchild. He would feign

braveness, but back off immediately—in both physical altercations with the same

sex and romantic entanglements with the opposite, talking the game of a

white-hot lover but, in practice, more of a horny bumbler. And then there was

the voice—“a nice Jewish boy gasping for air,” as writer Foster Hirsch put it—a

nasal Brooklynese that danced right up to the edge of a whine. His onstage and

onscreen patter was a tumult of stammers and mumbles, charging and

backtracking, pausing and rephrasing, all little tricks that created the

impression of nervousness and aimlessness, yet diverting us (his magician’s

training, that) from noticing the clever construction of the set-ups and punch

lines, or how masterfully he deployed those “um”s and “tch”s as part of the

musical rhythm of his joke delivery.

The timing was right for this kind of

character. Art goes in cycles, and the aggressive style of Milton Berle, Alan

King, and their ilk was on the way out. Allen’s approach was quiet, contemplative,

thoughtful. He objected to the label “intellectual comedian,” insisting, “I’m a

one-liner comic like Bob Hope and Henny Youngman. I do the wife jokes. I make

faces. I’m a comedian in the classic style.” However, his work was peppered

with references far beyond the scope of a Hope or Youngman, and while he did

“do the wife jokes,” much more of his material—and the best of it—looked

inward.

Woody’s rise coincided not just with a

proliferation of a more pronounced ethnicity in nightclub comedy, but—particularly

when he migrated from the stage to the screen in the 1970s—a shift in cultural

attitudes about masculinity and sexiness. Matinee idols like Redford, Newman, and Beatty

had to make way for the likes of Hoffman, Hackman, and Pacino, movie stars who

looked like real people. The triple-threat Allen would come to embody, in the

words of critic Diane Jacobs, “the struggles of late-twentieth century urban

man.” Woody himself put it another way: “My character was assigned to me by my

audience. They laughed more at certain things. Naturally, I used more of those

things.”

“Woody” was, as biographer Eric Lax writes, “a

hilarious creation concocted from a wildly exaggerated personal basis.” Allen,

as he has frequently protested, was no intellectual; he got lousy grades and

only read the Great Works of Literature to keep up with college girls he wanted

to bed. Like Leonard Zelig, he “preferred watching baseball to reading Moby Dick.” And Diane Keaton has said

that he had no trouble getting girls—particularly, we can presume, after he

became a stage and screen star.

The two halves of this split personality began

to merge in 1977, when he made “Annie Hall,”

his first film to draw on personal relationships and recognizable characters

rather than broad parody and wild verbal cartoons. Since the romance at its

center was mirrored by that of the actors dramatizing it, audiences and critics

presumed it was based on their relationship—indeed, this level of voyeurism may

have initially contributed to the film’s appeal. And from that point on,

puzzling out the genealogy of Allen’s stories, figuring out what was “real” and

what was fiction, became an inextricable component of Allen fandom.

The filmmaker objected—quietly, at first. “My

films are only autobiographical in the large, overall sense,” he said in 1980.

“The details are invented, regardless of whether you’re talking about “Annie Hall,” “Interiors,” or “Manhattan.”” He said this while promoting

“Stardust Memories,” about which he

predicted, “This is not me, but it will be perceived as me.” Was it ever. That

film’s portrayal of a harried filmmaker driven crazy by the demands and

inanities of his monstrous fans provoked a backlash, under the assumption that

this was, in fact, the opinion Allen held of those who admired him. Two years

later, he was still trying to explain it: “Not only did those things not happen

to me, I do not have those problems. I play a character who’s a filmmaker

because I’m familiar with the outer trappings of a profession like that. I can

write about them. I’m not going to make myself a nuclear physicist who’s having

a nervous breakdown, because I just don’t know what he’d do in the course of a

typical day.”

But the die was cast, and as the years passed,

Allen became less tolerant of all this talk of autobiography. “The public

doesn’t know me,” he told Eric Lax, “only the character I present to create

conflict and laughs.”

To be sure, viewing the entirety of his work

through the frame of autobiography is a minimizing approach. There is so much

to dig into that running every film through a life-to-art decoder misses what

is so valuable and remarkable about his fiction. But Allen himself admits that

the “dividing line between life, my own life and art is so indistinct, so fine

that it’s an obsessional theme with me.” In his book The Reluctant Film Art of Woody Allen, Peter J. Bailey writes of “Husbands and Wives,” “for Allen to

pretend that a film which insists (as many of his screenplays do) on the

autobiographical basis of art should be read completely in isolation from the

real-world circumstances that clearly inspired its mood, and certainly

influence its plot, reflects an equally oversimplified understanding of the

complex transactions between art and life which are his films and which so often

comprise the subject of his movies.”

In interviews, it often seems as though Allen

is conflating—deliberately, perhaps—the notions of memoir and autobiography. If

specific facts don’t jibe on a point-for-point basis, that doesn’t necessarily

make the work any less autobiographical. “Annie

Hall” was clearly inspired, at least to some degree, by the soul-searching

and loneliness he experienced after his relationship with Keaton ended, just as

“Husbands and Wives” was written in the

mindset that had not yet ended a long-term

relationship for a far younger woman, but was perhaps capable

of doing so.

From there, the line to “Deconstructing Harry“—a film about nothing less than the equally

productive and destructive inclinations of merging fact and fiction—is that

much clearer. As Foster Hirsch wrote in Love,

Sex, Death, and the Meaning of Life, “In caricaturing the public perception

of him as a sex-addicted workaholic—an image that Allen himself has fostered—he

seeks to defuse the prosecution. In giving so much apparent ammunition to his

denouncers—see what a prick I am, how I use people for my work, how

untrustworthy I am in affairs of the loins and the heart—he enforces a

countermove. . . . It’s as if Allen decided to paint a portrait so extreme that

his detractors might be coaxed into reevaluating their estimate of him.” And it

is that play with persona and perception, coupled with the film’s raw language

and attitudes (is this the real Woody

who’s been hiding all this time?) that gives the film its undeniable charge.

“I know it’s kind of a fun parlor game to

play,” documentarian Robert Weide says, “but I think in the long run, it’s a

little meaningless. In the same way that any author uses their own life

experiences, their own thoughts, and then infuses those things into their books

and into their work, I think Woody does that—no more and no less than any other

writer, or writer/director.” He may be right. Way back in 1974, a less-reserved

Allen told Eric Lax, “Almost all my work is autobiographical, and yet so

exaggerated and distorted it reads to me like fiction.” This may be the key to

understanding his films in relationship to his life—rooted in his own

experiences, loves, thoughts, and fears, yet, for him, turned into fiction once

it comes out of the typewriter. Once it’s out of his head and out in the world,

it is no longer him. But there’s also little doubt that the candor and honesty

of is what makes it so open and relatable to

those who view it; the more personal he gets, the more universal it feels.