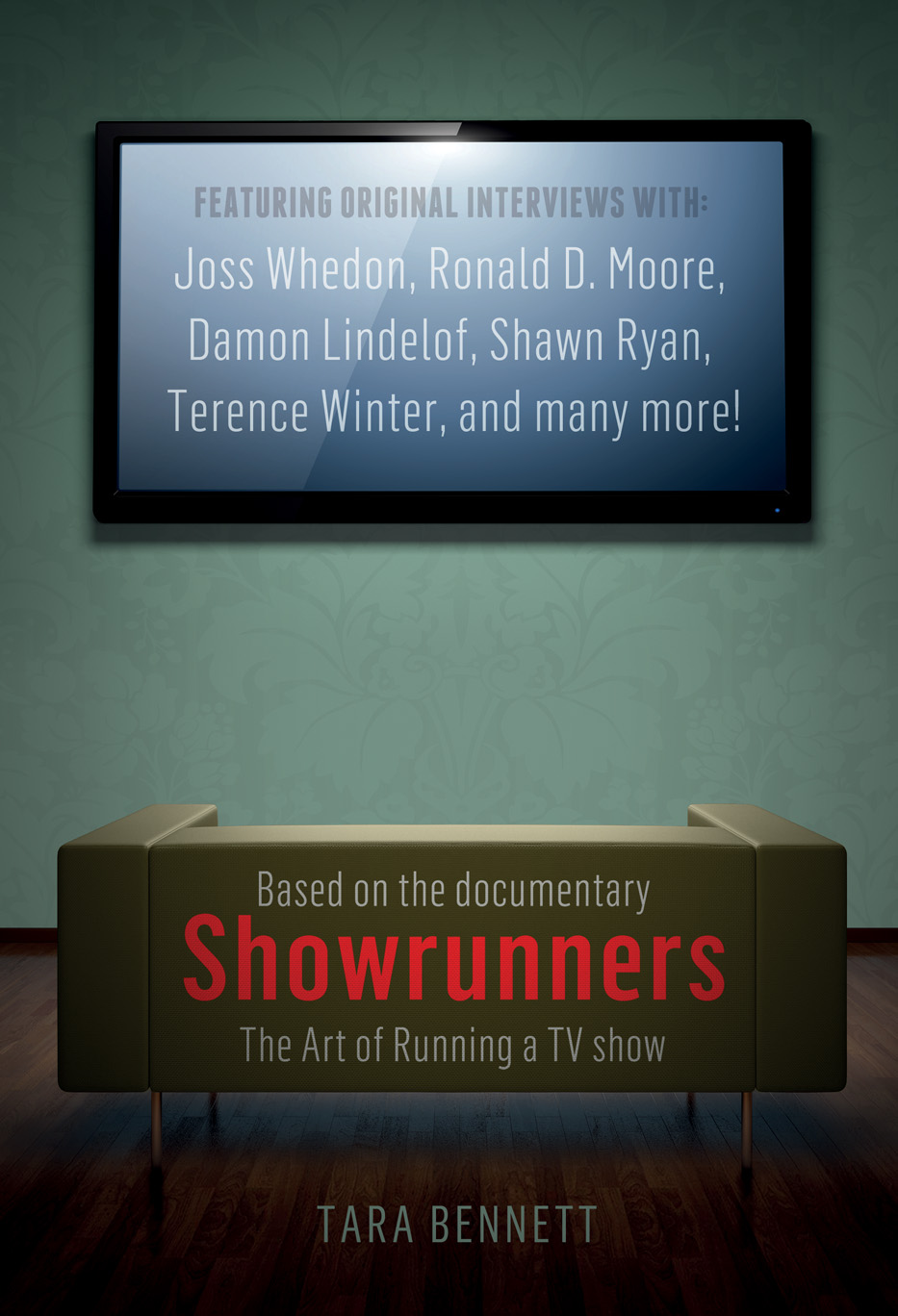

Below you’ll find an excerpt from Tara Bennett’s “Showrunners: How to Run a Hit TV Show,” courtesy of Titan Books. “Collected from a truly expansive exploration of television’s most creative minds, Showrunners is an insider’s guide to creating and maintaining a hit show in today’s golden age of television. The official companion to the documentary “Showrunners,” this highly informative book features exclusive interviews with such acclaimed and popular showrunners as Joss Whedon, Damon Lindelof, Ronald D.Moore, Terence Winter, Bill Prady, Shawn Ryan, David Shore, and Jane Espenson.”

Click here to buy it.

Basic TV Act Structure

As watching television has become more and more dominant as a cultural pastime, mainstream audiences have not only paid more attention to those who write it, but also the structure in which episodes are written.

Granted, we know it’s mostly critics, fledgling TV writers, and/or hardcore TV obsessives that pay attention to the structure in which a script unfolds, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t interesting, or have an incredible influence on the creative direction of a show.

To provide a little screenwriting 101, in the film world the three-act structure is the template that dominates screenplay writing. It’s based on the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s dramatic theory, The Poetics, from way back in 335 bc, which essentially explained that every good story needs a beginning, a middle, and an end.

Fast-forward to the television age where writers basically adapted one-act plays and three-act plays to the new medium. However, that traditional structure soon had to make space for advertising breaks, which essentially paid for the programme airing. Making a television show isn’t cheap, and it’s only gotten costlier. Thus, the three-act structure has expanded over the last 50 years to include an increase of commercial breaks (up to six in some hour-long shows) in both comedy and drama scripts, even though the allocated screen time has not changed (either 60 minutes or 30 minutes).

It’s only in premium or streaming-based television shows—like “Boardwalk Empire,” “Spartacus,” or “House of Cards,” which aren’t funded by advertising money but rather by subscriber fees—that showrunners still craft episodic stories in the three-act structure. There are no commercials, which means no ad breaks. But broadcast and basic cable television shows have to follow an act structure dictated by the network on which they air.

What does all of this mean? Essentially, that the majority of television writers have a fairly rigid template they have to write around. And it’s not an easy task. Showrunners help build a pace and tonal structure for their shows around their network-mandated act breaks, while also using all of those moments right before commercial breaks (or act outs) as an opportunity to leave the audience surprised or compelled enough to stick around during the ads. It doesn’t matter that so many of us fast-forward through our DVR’d recordings of a series, or binge watch on a streaming service where ads are moot. For now, the majority of the television industry still bases everything—even the creative flow of an episode—around advertising breaks.

JEFF MELVOIN, Showrunner: “Army Wives”

When you have to write for act breaks on broadcast television that means that you have to create space for commercials. You write your first act, which can be 10–12 minutes, and then you’ve got to break because they’re going to put in three or four minutes of commercials. After that, you come back. Writing for act breaks becomes an art in itself, because you can work them to your advantage. They give you certain freedom to do things in terms of continuity, jumping ahead in the story, or creating suspense. They’re not all bad, especially if you can zip through the commercials.

It’s a very different concept than running an HBO show, for example, where there are no act breaks because there are no commercials. Also, they don’t have to reach any specific length. We always, whether it’s in cable, basic cable, or in broadcast, have a very strict amount of technical specs you have to meet every week. The story content [for a drama] right now on broadcast and basic cable is 42 minutes including a 30 second recap. Every show has slight variations, but it’s always going to be [similar]. You can get variances, but the variances don’t extend more than usual. You can never be over because that means that they would sell less advertising. You can never do that, but you can be under sometimes because then they can sell more advertising. But you don’t want to be too far under every week, or they begin to not like that very much either.

JANE ESPENSON, Showrunner: “Caprica,” “Husbands“

When I came up in TV, dramas were in four acts. “Buffy The Vampire Slayer” was four acts and that means there were three commercial breaks. Let’s picture a loaf of bread: the three cuts make four pieces of bread, and so you got used to structuring a story like that. There’ll be a big turning point right in the middle of the loaf that changes everything, so it’s not even going to be pumpernickel anymore when you come back to this loaf. Then it started changing, and we got to five acts, and then six acts, and now some shows are six acts and a teaser, or seven acts and a teaser. There’s this inflation because they want to put more commercial breaks in, so you end up having to turn your story more often. You [write] six pages and you stop for a commercial break. Now you need that next six-page chunk when you come back to feel a little different in flavor than the first six pages, or that act break will feel like it didn’t quite land. You end up having to make all these little turns in the story. The problem is you end up with a very shallow, twisty story.

ROBERT KING, Showrunner: “The Good Wife“

The six-act structure will destroy storytelling, only because, even though the network or the studio will say, “Oh, don’t worry about having a strong act-out,” when they come down to it, they want a strong act-out, which usually means throwing some bullshit nonsense explosion in there of some kind. We are in a better position, in that [“The Good Wife”] has a five-act structure. They call it a teaser and four, but our teasers are very long, like 12 minutes long, so they’re really full acts. The problem is that you have to create strong act-outs that will pull people back, so it’s not very friendly to storytelling; it’s friendly to more “Bruckheimeresque” explosion storytelling.

MICHELLE KING, Showrunner: “The Good Wife”

We also have made a conscious decision to try to vary the structure from episode to episode which, hopefully, makes it a better viewing experience. It also makes it a more difficult writing experience for the writers in the room, and makes it more difficult to structure. We are trying to reinvent it all the time.