Editor’s note: Robert K. Elder made a splash a few years ago with his book “The Film That Changed My Life,” a collection of interviews with directors about a single film that influenced their career. Now he’s back with “The Best Film You’ve Never Seen,” (available through Independent Publishers Group) in which directors advocate for under-appreciated and critically maligned movies. Roger said of the new book, “How necessary this book is! And

how well judged and written! Some of the best films ever made, as Robert

K. Elder proves, are lamentably all but unknown.”

Here’s Elder’s interview with Guillermo Del Toro, director of this summer’s “Pacific Rim,” who sings the praises of “Arcane Sorcerer,” which Edgar Wright memorably described as “the ‘Barry Lyndon‘ of horror films.” The DVD of Avati’s film is no longer in circulation, alas, but you can watch a low-quality version on YouTube — for now, anyway.

Buy “The Best Film You’ve Never Seen” here.

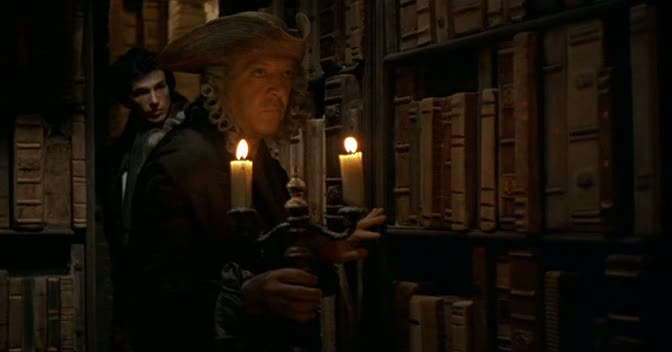

“Arcane Sorcerer” (1996)

Directed by Pupi Avati

Starring Carlo Cecchi, Stefano Dionisi, and Arnaldo Ninchi

Guillermo del Toro’s Catholic grandmother performed an exorcism on him not once but twice—hoping to guard his soul from the monster movies and fantasy stories he loved. It’s perhaps fitting then, that Del Toro’s choice for this book is Italian director Pupi Avati’s “Arcane Sorcerer.” This sixteenth-century story follows a disgraced young monk sent to look after an older monk whose soul may be in danger due to his knowledge of the occult.

But Del Toro had a tough time finding a copy of the film in the United States—until he found a DVD online. “It was a pretty bad-quality copy, but it had subtitles. And even in that absolutely ratty form, it completely compelled me,” he remembers. “It was incredibly powerful to see.” — Robert K. Elder

Elder: How would you describe the film to someone who’s never seen it?

Del Toro: It’s an incredibly well-researched, pastoral, spiritual horror movie. The rhythm and style of it are hard to describe. It’s the “Barry Lyndon” of horror films.

Can you tell me about when you saw the film?

I was at a showing of “Mimic,” and somebody said, “Your movies remind me of this movie, ‘Arcane Sorcerer.'” So I found a copy on the Internet. It was a pretty bad-quality copy, but it had subtitles. And even in that absolutely ratty form, it completely compelled me. It was incredibly powerful to see.

And it became incredibly important for me in doing “Devil’s Backbone,” for example. Just this idea that you can be pastoral in the landscape and imbue the movie with great horror, nevertheless. I love how Avati fuses the sounds of nature with the soundtrack—the cicadas and the crickets and the birds—until they become a source of mystery like they would’ve been at that time. The sounds of nature become the force of elemental creatures.

I’m a collector of old grimoires and old witchcraft texts and old occult literature. I have books from the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. I have a very nice library, and it’s incredible how close the movie comes to feeling like a true undocumented account of how this story would’ve happened in the time. It has an incredibly deep knowledge of the occult. Avati has an uncanny ear for the tone of this type of story, and it’s amazing!

And the story captures one aspect that is very rare in film or, for that matter, in modern literature, which is: prior to the seventeenth century and into the eighteenth century, the clergymen were incredibly knowledgeable and involved with the occult. They knew a lot about it. In fact, the best treatise on vampirism—or one of the best in literature—is written by a religious man, by Antoine Augustin Calmet, a Benedictine monk. And I think that it’s truly amazing how the movie captures how these clergymen were toeing the line between the holy and the unholy.

People who know your work and know Avati’s work might be surprised that you would choose this film. His other works, like “The Mazurka of the Baron, the Saint and the Early Fig Tree,” have that Fellinilike, fairy-tale influence that I think is reflected in some of your work. This film, on the other hand, seems to be almost a traditional gothic horror tale.

It’s not as traditional as you would think. The stakes the movie posits are beautifully intangible—they are spiritual stakes. What is at stake is the soul of the person. He’s not going to be destroyed physically; he’s not going to be chewed. He may be murdered in a ritual, but the main fear you have is for the soul of this guy, and that is very close to the stuff I like. I have seen Avati’s previous horror efforts, which were “Zeder” and “The House with Laughing Windows,” and I liked them both. I especially liked “Zeder.”

You’ve presented this film a few times in L.A. and Toronto. How does it play to contemporary audiences?

It seemed to play very well. I frankly was so enraptured seeing a brand-new print of it. And this was Mr. Avati’s print. So I thought it went well, but I didn’t ask much [laughs].

I’m doing my best to bring this film to the world. Avati is a curious filmmaker, and because his political leanings are to the right, he’s not a filmmaker that people analyze very deeply. I disagree with his political views, but I simply adore his filmmaking when it’s hot, and this movie is irrefutably great.

On the more philosophical side, this is a film about knowledge and specifically forbidden knowledge. For you, is there such thing as forbidden knowledge?

Well, I don’t think so. I think knowledge, as long as it comes with a spiritual component, is always great. What I don’t like is knowledge that is purely, purely intellectual, because that distances us from nature. I love the idea that knowledge can make us closer to the world, as opposed to making us feel superior to the world.

How do you think this film plays to people who were raised Catholic versus people who are outside the religion?

I think it definitely echoes more strongly if you are a Catholic. Because first of all, you understand more the morbid side of the Church and the morbid side of Catholic ritual, even. It really is easier to understand. It is a very strong movie purely from a cinematic point of view. One of the people I spoke to after the screening was Edgar Wright, who, in fact, is the one who coined the phrase “This is the ‘Barry Lyndon’ of horror movies.”

He was completely blown away by it. I think if you know anything about the craft of cinema from a filmmaker’s point of view, you understand how incredibly carefully crafted this movie is. A delightful confection. It’s superb. The art direction is superb. The cinematography, staging, acting, design, pacing, music, sound design are superb.

In one of your introductions to the film, you wrote, “It is the director’s eye for detail and pacing that makes us susceptible to the tenuous wonders at hand.” Can you tell me about the scenes or images that stick with you long after this film has ended?

Well, the pervasive atmosphere, certainly. I love the scene where a priest talks to what we think is a woman behind the portrait of the owl, which is, by the way, a highly significant bird in the occult. I love the scene where he sees the corpse that was buried, and his eyes are opened. That’s very, very shocking.

I mean, there are so many. I love the scene where he sees the apparition go through the library, and it’s a magical, absolutely magical scene, and one with very limited resources.

Your grandmother, who raised you, performed two exorcisms on you because of your love of fantasy and monsters. Did that experience, being the subject of an exorcism, fuel your curiosity for fantasy?

Well, it didn’t hamper it [laughs]. It was already fueled. Quite frankly, I’ve been an addict of horror and fantasy since my earliest memories.

Sure, but there’s a difference between watching “The Exorcist” and being the subject of an exorcism.

Well, she was not a pro. She was an enthusiastic amateur. I think it definitely didn’t take [laughs].

This film is also about a young priest who is seeking a mentor. Who filled that role in your life, and what did you learn from them?

Del Toro: Several of my teachers were very influential in shaping my taste in cinema. My screenwriting teacher in Mexico, my first cinema teacher in Mexico—they were instrumental. And they demanded a lot of sacrifice and fidelity to the craft that made me very disciplined, and I still carry it with me to this day.

You were also a protégé of Dick Smith, a makeup effects artist who worked on everything from “The Godfather” and “The Exorcist” to “Taxi Driver.”

Without Dick Smith, I couldn’t have done any of the things I’ve done. Literally none. God knows what my life would be! He was incredibly generous with his knowledge, not only with me but with everyone and anyone that wanted to learn makeup effects. Before Dick Smith, what would be “Arcane Sorcerer”? Makeup effects were a secret occult knowledge that was only allowed to be handled by a selected few. And Dick Smith came in and literally burst open the doors of that. He freely started to share it with people, to allow people to learn from him. He divulged the treatment, the techniques, and all of that. So, he is truly that: the maestro, the mentor—the most important mentor in my life, probably.

What did you learn from him?

The one thing he emphasized over any others was preparation. He used to say, “Prepare for the best, because that way you can deal with the unexpected.” He was not advocating to be inflexible, he was advocating to be prepared, and I still do it to this day. I’m as thorough and as well prepared as I can be in my filmmaking, and that came from the discipline of having to work as a makeup effects artist many, many, many times in my life.

You’ve often mentioned this film in the same breath as Paul Verhoeven’s “Flesh + Blood.” Did these two films share a link? They seem to hold a similar place in your heart.

I think they do. Because Verhoeven also captures the period in an incredible way by capturing the rhythms of that period. And he has an incredible sort of fantasy horror scene in that movie, where characters lie under the gallows and they talk about the mandrake root. And it perfectly captures the belief in the power of the occult and the supernatural as part of everyday life in that era.

Rarely anyone does that, because it’s hard to capture the fact that those beliefs were completely matter-of-fact. They were not argued with. When you think about our transition from the Middle Ages, and you think about the Age of Reason coming to be, we were still living in a world that was full of magic, dark and light.

And bringing that full circle back to Avati, one critic wrote that Avati’s films are often about the hidden or the obscure, especially his horror films. So why do we, as viewers, find that line so compelling, that tantalizing suspense until the moment we see what we fear?

It’s the same reason that we love hide-and-seek and love chases. One is the thrill of not knowing, and one is the thrill of knowing and experiencing. I think they are both fundamental columns of human narrative: to tease with a mystery or to pursue with action, so to speak.

But why, then, is horror so appealing? It’s been said that, as humans, we’re the only mammal that loves to scare the shit out of ourselves. Why is that uniquely human?

We’re the only mammals that arouse each other with tales or amuse each other with tales. The human act of storytelling is what sets us apart in the animal kingdom. There is no narrative drive, per se, in any other animal. The way, for example, bees communicate knowledge is through very, very precise geographic location, quantitative measures, where the flowers are, how much pollen can be extracted. But we adorn all these things with narrative. It’s fantastic. That’s what we do. And I think that that can be said about horror. Horror is one of the fundamental drives of storytelling. Comedy is another one, adventure is another one, and so on and so forth. You can end up identifying the genres through the millennia of narrative.

But why do we love to whack ourselves over the head with our own mortality?

I think horror is fundamental because as socialized mammals, we don’t get to experience the fight-or-flight and territorial battles in the way that other mammals do. We have socialized our existence, our geography, the limits of our geography and space, and social rules to a point where we cannot engage into a territorial fight that easily, and so forth. So we do it through movies and through narrative. Thinking and organizing life in a narrative that includes the beginning and the end—and what lies beyond—requires a storytelling process.

To bring this back to the “Arcane Sorcerer” and the afterlife, why is that spiritual theme more powerful?

Well, the deepest horror is the one that deals with the worst kind of things. When you’re dealing with somebody that may die or be maimed, you can always have the possibility of survival. There’s always that part of you that says, “Well, if I lose an arm, I would always have the other one” [laughs]. “Well, if the monster tears up my leg, I can always have a prosthetic one made or something.” But when you’re dealing with the soul, there is no solution to that. There are no prosthetics for the soul.

Guillermo del Toro, selected filmography:

“Cronos” (1993)

“Mimic” (1997)

“The Devil's Backbone” (2001)

“Hellboy” (2004)

“Pan's Labyrinth” (2006)

“Hellboy II: The Golden Army” (2008)

“Pacific Rim” (2013)

Excerpted with

permission from The Best Film You’ve Never Seen, published by Chicago

Review Press, June 2013.