If I were nine years old, I would see the monsters-versus-robots adventure “Pacific Rim” 50 times. Because I’m in my forties and have two kids and two jobs, I’ll have to be content with seeing it a couple more times in theaters and re-watching it on video.

Like George Lucas‘ original 1977 “Star Wars“, Guillermo del Toro’s sci-fi actioner uses high technology to pump up disreputable subject matter to Hollywood blockbuster levels. The film’s main selling point is its overscaled action sequences. In a terrified futureworld, spindly-limbed, whale-sized beasts emerge from a Hellmouth on the ocean floor and duke it out with immense robots. The robots are run by two-pilot teams whose movements suggest tai chi exercises taking place on the world’s largest, weirdest elliptical machines. They work in pairs because they use their minds and bodies to guide the machines in the way that puppeteers guide puppets, and the technology is too complex for a single brain to handle.

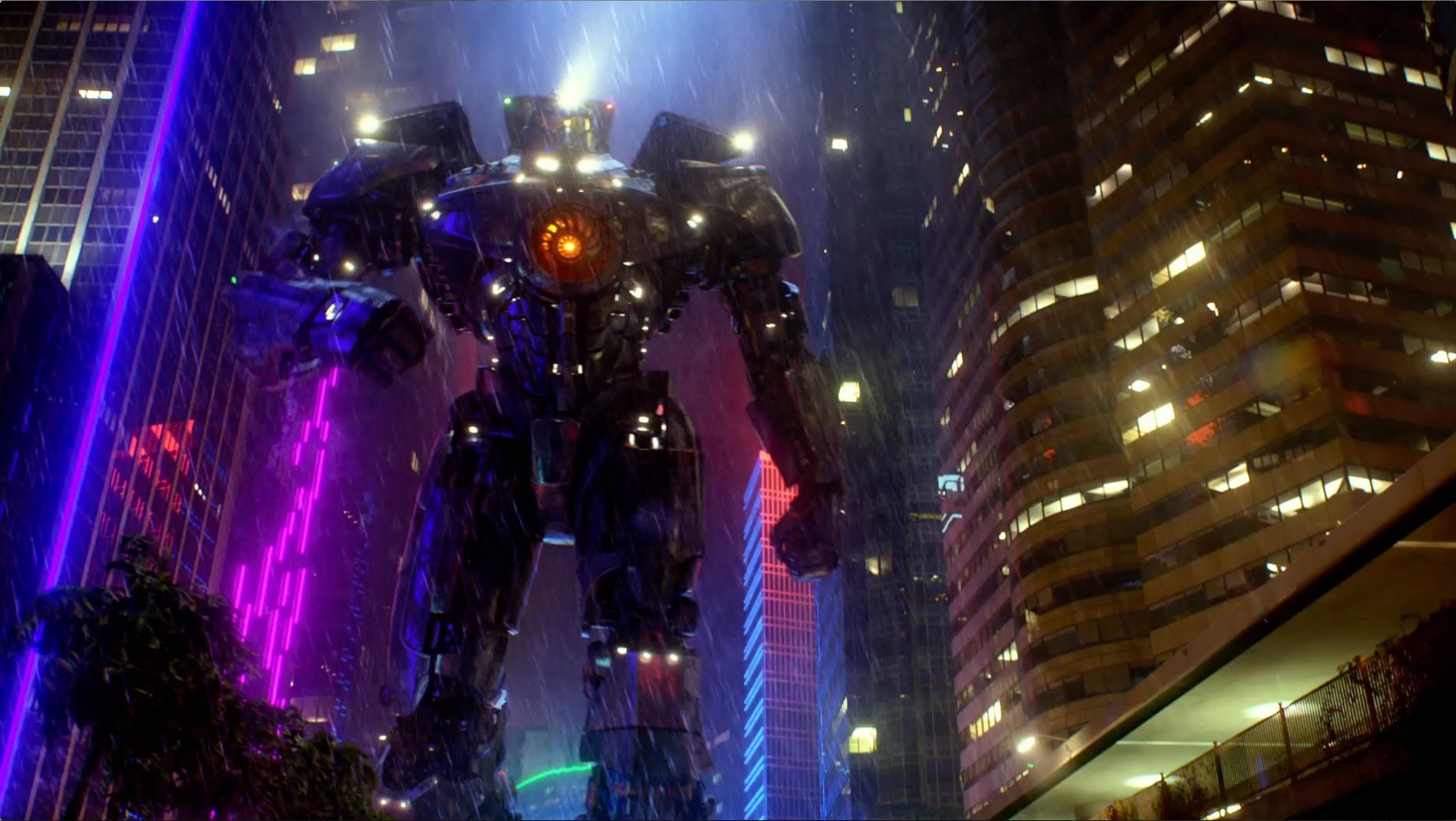

The creatures began attacking years before the start of the story proper (we get the history in a prologue). The humans can’t fight the monsters by conventional military means because it causes too much collateral damage. They created the robots — called Jaegers — to engage them directly, before the creatures, called Kaiju, could make landfall. Over time the beasts have become bigger, nastier, more resourceful, as if they’re evolving. And now they seem to be winning. Humankind is in retreat.

The fight scenes are often shot too close-in for my taste, and they go on too long, particularly during the final stretch — a problem that also afflicted”Iron Man 3,” “Star Trek Into Darkness,” “Man of Steel” and other recent summer films — and there are times when one of the combatants will use a weapon so devastating that you wonder why they didn’t just haul it out at the start of the fight and make the punching, kicking and flipping unnecessary.

Nitpicks aside, though, the fights are astonishing. They split the difference between classical filmmaking and the blurrier, more chaotic modern style in a way that made me appreciate the virtues of both. Some of the whirling action has a geometric beauty that’s faintly Cubist, and each fight contains surprises: a tactic you haven’t seen yet, a power you didn’t know about, a complication you didn’t see coming.

But for all its mayhem, “Pacific Rim” is a film with more more emotion than its trailers could have led you to expect. The hero, Raleigh Becket (Charlie Hunnam) is an ace pilot who gave up robot-piloting for coastal wall-building when his partner and older brother Yancy (Diego Klattenhoff) died fighting a monster. The pilots don’t just share physical responsibilities, they have unfettered access to one another’s memories, and must struggle not just to control their thoughts during combat, but to avoid being thrown off when their co-pilot lets a distracting or traumatic image slip through.

Raleigh thinks the bond he had with his brother can never be replicated, that his loss was irreplaceable. He learns otherwise when he’s paired with a young woman named Mako Mori (Rinko Kikuchi), who lost her parents in a Tokyo monster attack many years earlier. The story of their burgeoning partnership is not just that of pilot/copilot, but brother/sister, or friend/friend (but not boyfriend/girlfriend, refreshingly). It’s about learning to trust another person enough to allow their consciousness to fuse with yours.

The film contains many more examples of this sort of human dyad, including Mako and the robot fighters’ commanding officer Stacker Penetcost (Idris Elba), who feels fatherly tenderness toward Mako and doesn’t want her risking her life, and scientists Newton Geiszler (Charlie Day) and Gottlieb (Burn Gorman), who try to understand the kaiju’s biology, and haggle over whether to use an intuitive or data-based approach. (“Numbers are as close as we come to the handwriting of God,” Gottlieb says; he’s right, but not as right as he thinks.)

The movie’s action is physical, but it’s also metaphorical. The metaphors are articulated with such storybook directness and unabashed sentiment that by the end, I found myself thinking about what it means to be in a relationship, be it comprised of siblings, coworkers, lovers, or parents and kids. These people are all just comic-book types, with ridiculous names and cliched back-stories. But their feelings are real. They feel pain. They dream.

“Pacific Rim” stuffs each frame with multiple references to the latest iterations of what even geeks would call “Geek Culture.” But for all his fanboy enthusiasm, Del Toro is also a man of taste—that’s why he clothed Elba, the most dashing man alive, in a suit and tie rather than a standard sci-fi military general’s uniform. There are the expected shout-outs to Godzilla pictures and such robot-driven anime as “Neon Genesis Evangelion”, plus hat-tips to George Lucas (in the opening section, the hero’s older brother quotes Han Solo’s “Don’t get cocky, kid”), and way too many borrowings from the shlocky “Independence Day.” But there are also nods to Philip K. Dick, Ray Bradbury, Mary Shelley’s original “Frankenstein,” “2001,” “Brainstorm,” “Inception,” and the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft, whose descriptions of demon-creatures must have informed this picture’s effects. (Maybe now Del Toro will get to make his long-dreamed-of Lovecraft adaptation “At the Mountains of Madness.”)

There are many shots so striking that they could have served as the poster image: A Jaeger tumbling into an abyss, its E.T. heart pulsing; a little girl’s red shoe in a grey ash-heap on a rubble-strewn street; a kaiju unfurling kite-like wings; a one-eyed kaiju-body-parts dealer named Hannibal Chau (Ron Perlman) stalking through wreckage, his steel-tipped dress shoes jangling like cowboy spurs. A simple shot of Elba’s character taking off a helmet is infused with such emotion, thanks to its placement in the story and the sunlight haloing the actor’s head, that it would have made John Wayne cry.

Del Toro and his cowriter Travis Beacham have thought about how daily life, indeed consciousness itself, might change if something like this happened to the planet. There’s a hilarious clip of a TV talk show during the overconfident period in which humans thought they’d defeated the beasts: the host teases a giant sea-beast puppet that looks like an ugly, melted Barney the Dinosaur. The names of significant machines and locations have a fairy-tale rightness: “Shatterdome.” “The Bone Slum.” “Crimson Typhoon.” “Trespasser.” The sea walls and cityscapes seem beaten down, jury-rigged, exhausted. This world existed long before you started looking at it.

A few hours after I saw “Pacific Rim” for the first time, I had objections to one aspect or another. Days later I can’t remember most of them, and in the grand scheme, I don’t believe they matter, any more than the “flaws” of “Star Wars” or “The Wizard of Oz” matter. “Pacific Rim” knows what sort of film it wishes to be; it is that film, and much more. In its clanking, crashing way, it’s real science fiction, a play of ideas. It’s earnest in its belief that all thinking beings are part of a hive mind, or could be. You see the notion acted out onscreen in teams of two or three, in military units and small businesses, in city populations and whole species. This movie made me think of a line from Roger Ebert’s review of “Dark City,” which he described as “a film to nourish us. Not a story so much as an experience, it is a triumph of art direction, set design, cinematography, special effects–and imagination.”