BRIAN TALLERICO:

“I would like for them to say he took a few cups of love, he

took one tablespoon of patience, one teaspoon of generosity, one pint of

kindness; he took one quart of laughter; he took one pinch of concern. And, in

the end, he mixed willingness with happiness, he added lots of faith, and he

stirred it up well. Then he spread it over a span of a lifetime, and he served

it to each and every deserving person he met.”

—Muhammad Ali, when asked what he would like people to

think about him when he’s gone

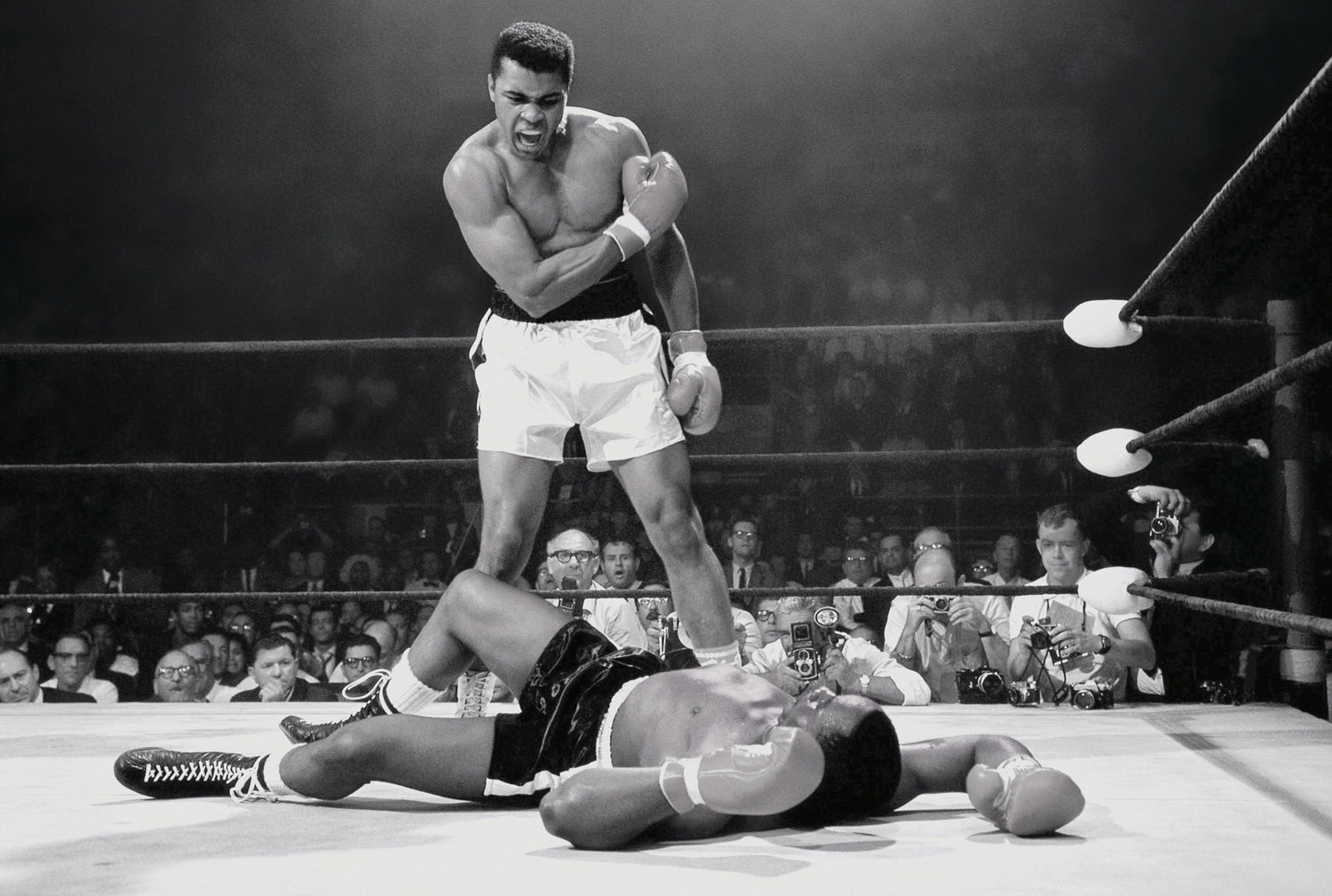

Where does one even start when it comes to talking about what

Ali meant? Look at that quote above. It’s an athlete who was arguably the best

at what he did but he doesn’t even mention boxing. And, to me, that’s one of

the elements that made Ali so special. Like a fighter in a ring dodging

punches, he was impossible to define with simple descriptors. His influence may

have been to illustrate to the world how multi-faceted public figures can be.

They can be the greatest of all time at their profession, but they can also be

powerful leaders in an anti-war movement, fundraisers for a fight against a

cruel disease, civil and religious rights icons, and even playful poets. Ali’s

impact is so hard to put into words because he was a man who refused to be

simply defined. And he taught generations that they shouldn’t be put in boxes

either. Fighters can be peaceful. Athletes can be poets. Men can be beautiful.

And only one man can and ever will be Muhammad Ali.

SERGIO MIMS:

Please don’t misunderstand me. Not that I’m bragging, but I

have in my lifetime met a lot of famous people. Comes with the job and my

interests, but I can honestly say that only one time in my life was I truly

intimidated by someone who was famous.

And that person was the one and only G.O.A.T.: Muhammad Ali

It happened many years ago, just shortly after he retired

from boxing. Someone I know had gotten an invite for a fashion show for which

he was a celebrity judge. Knowing how much he meant to me, my parents, and my

grandfather, I decided that somehow I would get Ali to sign the program book

for my grandfather and send it to him.

When I arrived for the show, I looked for him. There was

Ali, larger than life. Nervously, I slowly approached him. What would he be

like? Would he turn me away or ignore me? Would he crash my dreams of who he

was?

As I got closer, Ali turned to ME, and extended his hand for

a handshake. I shook his hand, and, with voice trembling, asked him if he could

sign the program book for my grandfather. Of course he would. He took my pen

and asked for me grandfather’s name, which was (no joke) Ebenezer. That made

him chuckle, and he joked why didn’t I ask for an autograph for myself as well.

After he signed it, he put his hand on my shoulder and said “You tell

Ebenezer I said ‘Hello.'”

Somehow, with my legs shaking, I made it back to my seat and

spent the rest of the evening watching him while he was watching the gorgeous models

on the runway. But that’s the effect he had on me and I assume most people.

For me, growing up, Ali was more than just a famous person,

more than the greatest boxer of the past century. He was the living embodiment

of black manhood—unbought, unafraid and true to himself.

He said and did what he believed without fear of

consequence. He threw his Olympic boxing gold medal into the river in protest

to the racism he experienced in this country and constantly spoke out against. He

converted to Islam and changed his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali and

was close friends with Malcolm X. He spoke out against the Vietnam War and

refused to enter military service objecting to the war and the U.S. government

foreign policies. And he did it all with courage, grace and even humor. He took

on the establishment and the powers that be and always wound up victorious. He

was like no other.

And that was the person I met that night and who I have

admired my entire life. A man who lived his life the way he wanted to live—uncompromising

and always truthful about what he said and believed.

He was, he is and he always will be The Greatest of All

Time.

STEVEN BOONE:

My absolute favorite memory of Muhammad Ali is a stray,

quiet moment from the otherwise explosive documentary “Soul Power,” the musical

counterpart to “When We Were Kings.” It’s early morning on Day One of the music

festival designed as a counterpart to Ali’s legendary Rumble in the Jungle bout with George Foreman, in Kinshasa, Zaire.

But right now Ali is just focusing on pouring at least five spoonfuls of sugar

into his coffee. He radiates so much energy, you wonder why he needs the

caffeine, or the sugar.

He turns and spots someone, his face lighting up.

“Stokely Carmichael!” he shouts. The camera pulls back to reveal

Kwame Toure, the civil rights icon who had changed his name from Stokely

Carmichael and left America to become an official in the government of Guinea,

walking up to the champ. “Don’t you burn up nothing over here!” Ali

says as they shake hands, both grinning like kids. He turns back to his

breakfast companions, eyes gleaming, and takes a sip of his coffee with a

spoon, staring down at it while clearly still savoring his own joke. Without

even seeing Toure/Carmichael at this point, you just know that he is walking

away beaming, too.

Carmichael had been accused of inciting riots in Washington,

D.C. right after Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, just one of many

attempts by the FBI and CIA to neutralize him.

So here he was, six years later, more of an African

dignitary than the boyish American revolutionary Ali once knew, but the champ

calls him by his birth name. That’s like Toure calling Ali “Cassius

Clay.” In that simple choice of address, Ali evokes their shared history:

When young Carmichael was fighting American apartheid and imperialism, Ali was

in jail for standing up to the same evils.

What I love about this moment is how much intelligence is

conveyed in one handshake, one impish smile and one sugary cup of coffee. Even

if you don’t know the history surrounding this wisp of a moment, Ali’s

embracing, teasing presence makes it universally relatable: two great men

acknowledging each other in a casual, down-home way. Ali was a brilliant author in the genre of

life itself.

SHEILA O’MALLEY:

I feel so fortunate that I grew up in the era when Muhammad

Ali was an omnipresent cultural figure, a regular guest on “The Tonight Show

with Johnny Carson,” where his banter, humor, improvised rhyme schemes, and

gentle yet commanding presence (how did he pull off that combination so

effortlessly?) were an onslaught of charm and personality. My love of boxing

would come later. I knew he was famous for being a boxer (I picked up on that

by osmosis), but what I mostly sensed—and we’re talking at age 6, 7, 8—was that

this was a good man, a special man. I knew he was funny and I understood his

humor. Malcolm X once said of his protégé and friend, “Though a clown

never imitates a wise man, the wise man can imitate a clown.” I totally

picked up on that. So many adults seemed incomprehensible to me and he came off

as completely transparent. He wasn’t on my level. He was on EVERYONE’S level.

Outside of being a boxer, outside of being a man of convictions, political courage,

compassion, strength, he was also an entertainer and he took that seriously. He

knew what people wanted from him, and he provided it with panache. That is

old-school generosity and, unfortunately, a lost art.

There are scenes in Albert and David Maysles’ extraordinary

documentary footage of Ali training to fight Larry Holmes in 1980 (now

resurrected as “Muhammad and Larry,” an episode in ESPN’s “30 for 30”

series) where onlookers and fans (kids, old men, young women, teenage boys)

push up against the ring, watching Ali spar with his trainer and other boxers.

He had a magic about him. It came from the inside. Beyond his awe-inspiring

athleticism and gorgeous 6’3” body, he had a glow that people wanted, needed.

You can see it on their faces. What would it be like to be as confident as Ali?

What would it be like to have his self-knowledge, humor, competitiveness,

kindness? Maybe if people got close enough it would rub off, maybe Ali’s secret

would be revealed, the secret of what it is like to be a man who knows who he

is, and is present in every moment.

We all could use a little more of that.

It was later that I understood what he signified, what he

had accomplished as a boxer, as well as the other well-known facts of his life:

his actions during the Vietnam War, his name-change, his relationship with

Malcolm X. But once I went back and watched footage of him in the ring, I was

so struck by his light-footed dodging and weaving, such a startling thing to

see in a man so big, so muscular. He made his opponent do all the work; he

bided his time; he saved his strength with a dancer’s grace. He was spectacular

to watch.

Recently, I read Peter Guralnick’s “Dream Boogie: The

Triumph of Sam Cooke,” and Ali plays a huge part. He and Sam Cooke were

dear friends. In March of 1964, they went into the studio together to record a

song, “Hey, Hey, The Gang’s All Here.” A couple of days later, the

two were interviewed via transatlantic connection by British boxing commentator

Harry Carpenter. The mood is jovial and affectionate (Ali starts off by

introducing Cooke, adding, “As you can see, he’s like me, awful

pretty.”) The two sit close together, and there is such a strong thread of

connection between the men that it is visible. The two of them sing the song

together, a cappella, and it is one of the most charming, open and fearlessly

free performances I have ever seen.

With all of the things Ali did in his life, it was this clip

that I first thought of when I heard the news.

JESSICA RITCHEY:

My sister and I were watching the opening ceremony of the

1996 Summer Olympics in Atlanta with our father. I was enjoying the spectacle,

masked figures waving their arms and groups of athletes marching in file under

their flags. It came time for the final leg of the Olympic torch race. A woman

jogged up the ramp and a man came forward at the top. And my father’s whoop of

surprise nearly startled me off the couch. I read the chyron, the man was

Muhammad Ali. As he bent to light the cauldron I kept looking at my father. He

had walked closer to the little TV set and was crouching down like he wanted to

crawl into it. He had a smile of pure delight and admiration. For all the times

adults had told me “so and so” was a big deal, I understood clearly from my

father’s body language that this time it was true.

This person is

important. This person matters.

It was an initial impression that would only be confirmed as

I grew up to learn about Ali’s accomplishments and his political activism. How

he had a faultless instinct for show business brio while at the same time not

caring about making a white establishment comfortable with his abilities and

the clear pride he took in them. 2016 has truly become a monster, gobbling up

our icons, one after the other. At my worst, I worry the culture is losing

people it can’t afford too. But I think a more universal truth is being

revealed in these passings. Some people when they’re gone, you know you will

not see their like again.

PETER SOBCZYNSKI:

I have never been much of a follower of the sport of

boxing—I recognize the amount of skill and strategy on display in a good match

but when all is said and done, watching two guys getting their brains beaten

into jelly has never been my idea of entertainment—but the greatness of Muhammed

Ali was of a type that transcended the ring and touched people around the

world. As an athlete, he was without comparison, and even those who did not

care for boxing could not help but be impressed with his unheard-of combination

of sheer ferocity and balletic grace. Outside the ring, he first impressed as

perhaps the first truly media-savvy athlete of the modern age—at a time when

most sports stars were expected to be both humble and monosyllabic, he would go

off on flights of oral fancy that combined humor, braggadocio and sheer poetry

in ways that were a joy to hear. Before long, he would use his gift of verbal

dexterity to help demonstrate the courage of his convictions, first when he

made the controversial conversion to Islam and then when he proclaimed himself

a conscientious objector to the war in Vietnam. Considering how universally

beloved he would become in later years, it is startling to realize just how

hated he was by a good percentage of the population for sticking to his beliefs,

but rather than sell them short in order to make things easier for himself, he

clung to them at enormous personal cost. That alone would be enough to earn him

universal admiration but to then come back and regain everything that he had

lost thanks to his incredible athletic prowess ensured his place in the

pantheon of sports history. However, by using his fame, his power and, for as

long as he could use it, his voice to try to make the world a better place by

bringing people together, he truly lived up to his nickname, “The Greatest.”

Now he is gone and while that would be a sad and distressing

event under any circumstances, it is even worse because he has left us during a

time in which racial strife and hatred/mistrust of Muslims is making a

distressing return. Will another Ali come along to help us see that there is

another way beyond the path that we have been stumbling down as of late?

Probably not—Ali was a true original and while many have tried to follow in his

footsteps, it is doubtful that anyone will ever be able to truly fill them.

However, if everyone who has been posting tributes to Ali and his legacy on

Facebook and Twitter—even Donald Trump, who tweeted words of praise even though

he only last December tweeted “Obama said in his speech that Muslims are our

sports heroes. What sport is he talking about, and who? Is Obama

profiling?”—would actually practice a little bit of what Ali preached about

peace and tolerance in real life instead of simply paying lip service to it via

social media, we might not need another because that would be a far more

tribute to the man and his legacy.

GLENN KENNY:

Norman Mailer, no slouch in the ego department himself,

eloquently argued that ego was a key component in the success story of Muhammad

Ali. And while all professional writers are egocentric by definition, my own

ego isn’t so big that I think I can in any way compete with the amazing writing

about Muhammad Ali that’s come down through the years of his incredible life

and career. Sure, I could tell you about how I looked at Ali in my ‘60s

childhood and various “feels” associated with that but seriously, your time

would be much better spent reading, for instance:

“Ego,” the essay by Norman Mailer, ostensibly about

Ali/Frazier, anthologized in “The Best American Sports Writing of the Century,”

edited by David Halberstam. It is one of the last six pieces in that book, all

of which are about Ali and one of which is…

Murray Kempton’s seminal “The Champ And The Chump,” about

Sonny Liston and the future Muhammad Ali. Kempton’s Manichean portrayal of the

two men was arguably wrong-headed (and is refuted to an extent by Nick Tosches

provocative biography “The Devil And Sonny Liston”), but it remained fixed in

the culture for decades…

Mailer’s book “The Fight” about the Foreman/Ali battle in

Zaire; an arguably “indulgent” book but also a remarkable dissection of machismo

and racialism and, again, ego…

James Baldwin’s “An OpenLetter To My Sister, Angela Y. Davis” only mentions Ali in passing, but is

essential reading for understanding the context of Muhammad Ali; and finally…

“Anti-Poetry Night,” by A.J. Liebling, a largely

affectionate but occasionally bemused portrait of then-Cassius Clay in spring

of 1963. It ends thusly: “Will he ever be heavyweight champion? Time will tell.

Will he learn to punch harder? It is a question of time, too. Will he learn to

fight inside? Time is all. A young man’s best friend is time.”

PABLO VILLACA:

The upcoming ESPN epic documentary about O.J. Simpson,

“Made in America,” promotes a very interesting reflection about the

role of an idol when it comes to politics and race issues. Although he became a

very successful athlete in a time that would make his African-American heritage

incredibly important if put to political use, Simpson never saw a reason for

“risking” his position and his fame by speaking out against the

terrible injustices the African-American community was (and still is) suffering

in a daily basis.

Well, that’s one of the key things that differentiate an

O.J. Simpson from a Muhammad Ali.

If Simpson was an incredibly talent artist, Ali was Mozart.

His genius made a sport based on brutality become a form of Art. His taunts

were performance art in its most compelling, his moves on the ring were Gene

Kelly-level dancing, his strength and resilience were just plain inspiring. It

takes a special form of brilliance, self-confidence and craziness to put

yourself in the corner of the ring, extend your arms to the sides, bracing the

ropes, and to face an opponent with an exposed face, using merely your agility

to avoid a barrage of 21 punches by…dodging.

And still, if he was unique as a boxer, it was his

convictions and his character that made him a legend. The conviction to refuse

to go to war in the name of what was basically a power play with ulterior

political and economic motives; the conviction to use his fame and influence to

help his community against the same system that wouldn’t hesitate in sending

African-American boys to die in Asia and wouldn’t lift a finger to stop them

from dying in America; the conviction to go to jail for what he believed.

THAT’s what makes a true champion.

And the fact he beat Superman himself and also an alien

boxer, saving the Earth in process, doesn’t hurt.

OMER MOZAFFAR:

I’ve studied his matches over and over again. The books

about him. The movies. Why: because even though he was hated hated hated, he

persisted with force and love. For this Muslim kid from the South Side of

Chicago, who has so often prayed in his mosque on 47th street, who shook his

hands at Eid prayers decades ago, he was sometimes the only reminder that even

in the face of the most vicious, most ignorant hate, you persist and you win.

Then he was revered. Ultimately, he was adored. Now, I am heartbroken. But, the

fight continues.

MATT ZOLLER SEITZ:

Muhammad Ali wholly or partly inspired many fictions

featuring Ali or Ali-like characters, but none were as interesting as Ali

himself, or for that matter, any randomly chosen still photograph of Ali. In

one sense, it was inspiring to see the mainstream, which was understandably

preoccupied with stories about people who looked more or less like the people

making film and TV shows, becoming fascinated with Ali and wrestling with the

implications of Ali’s athletic genius, intellect, artistic temperament, and

worldwide popularity.

But it wasn’t until Michael Mann’s excellent, still

underrated “Ali” came along in 2001–twenty years after Ali had retired from

boxing and begun to stammer and shake from Parkinsons’-related problems– that

any scripted film could deal with Ali as Ali, rather than as a

half-metaphorical being reflecting white attitudes about race back at them, in a

kind of cinematic referendum on enlightenment. The 1970 film “The Great White

Hope,” which starred James Earl Jones as a black boxing champ in the 1920 who

was bedeviled by racism and his own pride, was the first. Although ostensibly

the character was based on Jack Johnson, a likewise militant figure who

dominated the sport forty years before Ali/Cassius Clay came on the scene, it

was also a reaction to Ali’s defiant individuality, political radicalism and

unapologetic blackness. Ali would play himself in a mostly regrettable 1978

biopic, and become the subject of innumerable documentaries, the best of which

is “When We Were Kings,” about Ali’s 1974 comeback fight against George Foreman

in Zaire. Ali’s embrace of his African heritage is treated as the psychic fuel

that enabled him to triumph over Foreman, an aloof-seeming fighter that

Zaire-based fans saw as a representative of colonial white values. Mann’s film,

a more atmospheric, mythic take on the post-draft-board period of the fighter’s

life, draws much of its power from re-creating key moments from “When We Were

Kings.” The emotional high point is Ali (played by Will Smith in perhaps his

greatest screen performance) jogging through shantytown streets as he’s cheered

on by local residents and tailed by adoring children.

The first three “Rocky” movies were partly about white

anxiety over the certainty that they’d eventually be displaced from the center

of American life and culture. The underdog is a working class white man. The

champ, Carl Weathers’ Apollo Creed, is a complacent rich black man whose

taunting patter and quicksilver moves were modeled on Ali’s. (Ali talked about

what Stallone’s script and Weathers’ performance took from him while watchingRocky II with Roger Ebert.) The “Rocky” version of Ali is, of course, almost

entirely divorced from any larger political context, so that he becomes a

purely physical threat, an obstacle for Rocky to overcome as he tries to prove

he’s somebody. (Stallone wrote the script after seeing a white fighter, Chuck

Wepner, aka “The Bayonne Bleeder,” go fifteen rounds against Ali in

1975, a loss that was seen as a victory for the indomitable spirit of the

underdog.) And while “black-vs.-white” is a subtext in the first

film, as well as the sequels, skin color is rarely remarked upon in dialogue—the

better to universalize Rocky as a working stiff just trying to take his best

shot at an impossible dream, and make it possible for viewers of any background

to imprint their own experience on him and identify with him (and millions did—the

first three Rockys are sensationally effective films).

In the third film, Rocky has become Apollo in Rocky I,

coasting along on the fumes of his rematch victory in Rocky II and growing

soft; the Ali stand-in helps him defeat a frighteningly confrontational black

challenger, Mr. T’s Clubber Lang, who sees Rocky as a chump, not a champ. And

so, through the magic of writer-filmmaker-star Sylvester Stallone’s populist

alchemy, we see a universalized version of a humbled, empathetic Ali helping a

white boxer beat a white-paranoia-fueled image of Ali’s radical,

confrontational 1960s self—a snarling fast-talking up-from-nothing usurper,

telling white America right to its face that it its dominant position was

earned through luck and trickery, not merit or divine right. In the fourth “Rocky,”

the Ali character dies fighting an emblem of Communist aggression. He

sacrifices himself on the altar of the very beliefs that the real Ali gave up

boxing to oppose, when he refused induction into the Vietnam War. “Why

should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop

bombs and bullets on Brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in

Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?” Ali

asked in 1968. In the same year, 1985, that Stallone killed off the Ali

character in his fourth Rocky installment, his other great character, the

former Green Beret Rambo, re-fought and won the Vietnam War in “Rambo II,”

machine-gunning bushels of Vietnamese soldiers (who were caricatured like

“Japs” in a World War II war movie) and Soviet advisers (the Rambo

films’ stand-ins for Nazis).

The Rocky films are nigh-irresistible entertainment, beloved

by an international cross-section of fans. But there’s no denying the wish

fulfillment aspect of a white boxer rising to the top after nearly twenty years

of the sport being dominated by African-American boxers, the greatest of whom,

Ali, was also a polarizing figure, a man who stood in opposition to nearly

every political value that Stallone, as a movie star and auteur, reinforced in

his screenplays. The Rocky movies change the spelling of Ali’s last name,

taking away the “i” and adding an “ly.”

It wasn’t until Ryan Coogler, an African-American filmmaker,

took over the franchise with last year’s superb “Creed” that the Apollo/Ali

character was given his rightful due. Among other things, we learn that Rocky

and Apollo’s legendary third match, which happened at the end of “Rocky III”

after Apollo taught Rocky how to fight with rhythm and soul (i.e., like a black

man)—ended with another loss for Rocky. The film’s handling of this moment

exudes humility: when Apollo’s illegitimate son Adonis “Donny”

Johnson (Michael B. Jordan) asks who won that third match, Rocky replies,

quietly and with a touch of wonder, “He did,” as if the idea of any

other outcome is so absurd that he’s surprised to hear the question.

Donny, too, is haunted by the image and impact of Creed/Ali,

who hangs over every frame of the film, infusing it with his spirit. He

shadow-boxes against projected footage of his father, emulating his moves and

drawing strength from his image, and during the final fight, he gets up during

a ten-count when the champ’s image rushes into his barely-conscious mind. It’s

as if a spirit has taken over his body—as if Apollo/Ali has become his unseen

second coach. The film’s acceptance of a non-white boxer’s dominance of the

sport feels like a long-delayed corrective to a scenario that was a fantasy all

the way back in 1976. Rocky resists helping Donny at first but soon relents and

is as selfless in his devotion to his late friend’s son as Apollo was to him in

“Rocky III.” The most politically

resonant shot in the entire film isn’t from a fight or a training montage,

though those are brilliantly realized, but in a long tracking shot following

Donny and Rocky into the ring en route to the final showdown. On the back of

Donny’s robe it says “Creed.” On the back of Rocky’s it says

“Creed’s Team.” The entire film, and especially Rocky, are rooting

for a black man’s success. Ali made that possible decades earlier; it just took

Hollywood forty years to catch up.