Money in your pocket. A morning of clear skies. A vast, untamed landscape, or years and years ahead. Few things are as intoxicating as a sense of endless possibility, and it’s that sense, above all others, that defines the fourth season of “Outlander.” But there’s a downside to any landscape in which anything is possible. Good things can happen, sure, but trouble can creep in, too. That’s true in life. It’s true in marriage. And it’s true in the creation of television shows. Intoxication can feel wonderful, but it can impair your judgment, too.

If that sounds vaguely ominous, it’s not meant to. Not really. There’s still plenty to recommend in the fourth go-round of the popular Starz epic, including but not limited to its predictably lush cinematography, uniformly excellent costuming and production design, and performances that range from solid to remarkable. There’s also a hell of a good yarn to be spun—the Diana Gabaldon books from which the series is adapted just placed second in “The Great American Read,” between “To Kill A Mockingbird” and the “Harry Potter” books—and the fact that, for the most part, the people telling the story do so with enjoyable panache. But some of the stumbles from the show’s mixed-bag of a third season reoccur here, and the occasional new misstep threatens to diminish the show’s other pleasures. Still, when the show focuses in on its central pairing and those most connected to their lives, it’s as immersive and irresistible as ever.

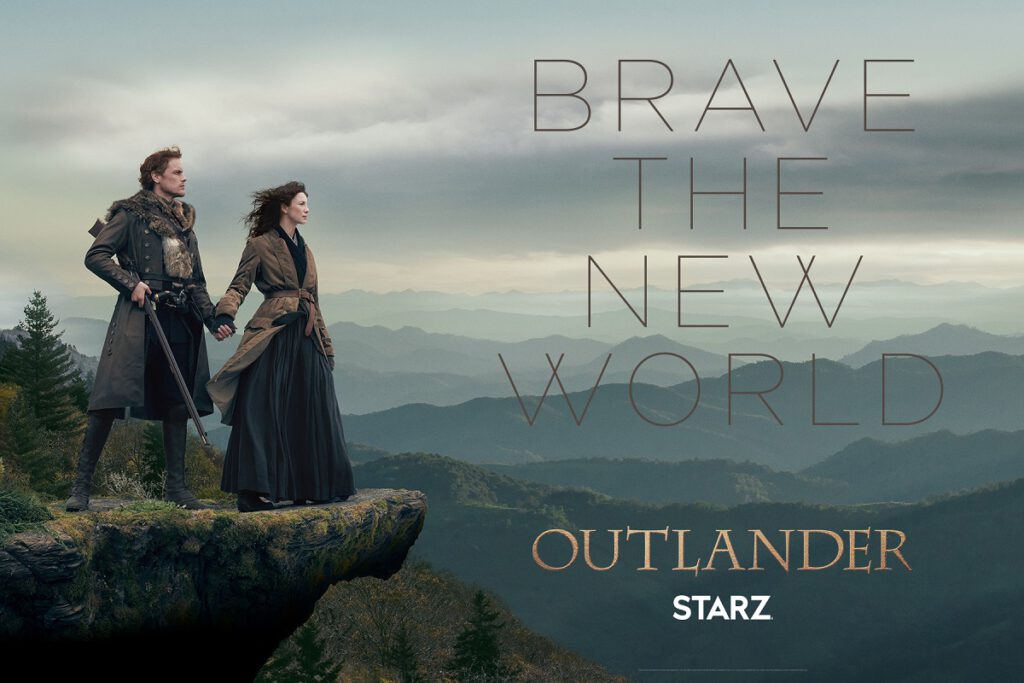

At the end of season three, we left Claire (Caitriona Balfe) and Jamie (Sam Heughan) Fraser—he, a Scottish Highlander of the 18th century, she, a time-traveling British battlefield nurse-turned-surgeon who served in the Second World War—she’d once again returned from the future, leaving a daughter in the late 1960s to find the man she loved. On arriving back in the past, the pair end up chasing some kidnapping jewel-thief pirates (it’s a long story) all the way to the New World. After some murder, witchcraft, political maneuvering, several big storms, and a lot of time on boats, they land in Georgia—without a dime, but free to be themselves and together for the first time in many years. As season four begins, that’s still true, but as is always the case with this couple, there’s chaos with which to contend.

A lot of that chaos centers on death and trauma. Of the six episodes released to critics, there’s not much that can be said—nearly all the plot developments are embargoed, as is much concerning both new and returning characters—but to say that there’s a sense of darkness that belies the gorgeous, sunkissed photography is an understatement. At its best, that darkness stems from three seasons and two-plus decades worth of history. A standout scene between Jamie and his nephew Ian (John Bell) addresses the way that trauma—in this case, the trauma that can spring from sexual assault—sometimes lingers for months, years, or even decades; that it takes place in a graveyard beside an empty coffin in the middle of the night should make clear both the tone and the show’s occasional reluctance to chill. That’s one instance among many in which the through-line of grief, loss, and cruelty succeeds.

There are others that aren’t as successful. In the third season, the arrival of the Frasers in the West Indies led (as is the case with the books) to the show’s grappling with slavery. The results weren’t promising. Season four fares at least somewhat better, as the arrival of the Frasers as relative Jocasta Cameron’s (Maria Doyle Kennedy) plantation forces them to confront the harm even the best of intentions can inflict when those acting don’t ask those they’re attempting to help what they actually need. But when the Frasers head into the wilderness, their interactions with the Cherokee population range from much more thoughtful to frustratingly heavy-handed and even silly. The events themselves could be successfully told, both those taken directly from the books and those that are an invention of the show, but a tendency to always add one more layer, one more scare, one more piece of meaningful slow-motion or drum-laced music cue sometimes threatens to drag the series down. Heavy-handedness can be forgiven, but not endlessly so.

<span class="s1" Thankfully, there’s plenty about this season that’s neither too hot, nor too cold, but just right. First and foremost among these strengths: a cast that grows stronger by the year, anchored by a thoughtful, often thrilling performance from Caitriona Balfe. With Claire firmly planted in one time period, Balfe gets the chance to play more of the little, everyday stuff that defines a life, and as good as she is when the world seems to be coming apart at the seams, she’s even better when Claire has goats to feed, patients to tend, and a husband to quietly (or not so quietly) cherish. Balfe has always been terrific, while Heughan has improved year after year, here seeming more relaxed and at home playing a frankly unrealistically magnificent man whose years of suffering have not hardened him to the beauties and pleasures of life. Kennedy and Bell both give engrossing performances, the former especially so, while Ed Speleers of “Downton Abbey” takes a role that might have swallowed a lesser actor alive and turns in something vicious, putrid, and disturbingly forceful.

To cap it all, two of the series’ most reliable players return near the end of the season’s first half. These two actors inhabit their characters with easy confidence and honestly, and their arrivals, one on the heels of the other, seem to trigger a major shift in quality, elevating what the good to something remarkable and whole. The arrival of the first is easily the season’s most electrifying moment, and of all the threads not named Claire or Jamie the show weaves together, his is the one I’m most interested to tug.

Characters old and new alike have a bit more of a struggle than they have in seasons past, thanks to the occasional piece of creaky dialogue—I actually said aloud, “Please don’t say it,” in the long pause before one of the show’s best actors delivered a line that was telegraphed from miles away—and the aforementioned tendency of the show to do just a bit more than is necessary. (We see the same magnificent view over, and over, and over again, and never without a remark on how powerful the sight alone is to all who behold it.) And there’s no particularly graceful way to say this, but the series also suddenly feels much more chaste—not a small thing for a series that was, for some time, the sexiest thing on television. It’s not as though these characters aren’t having sex, but it certainly seems as though “Outlander” is suddenly a lot less interested in the intimacy and dynamics of those sequences than it was in previous years. Put another way: Not every show needs loads of doin’ it, but “Outlander” was best in class, and now that’s gone. What happened?

That’s a lot of negative up there, I know. But when you love something, acknowledging its flaws is important. That’s true in the relationship on which this show centers, and it’s true of the show itself. At its best, “Outlander” tells the story of a marriage and its ups and downs as well as anything else on television. It’s sexy and smart, frustrating and thrilling in equal measure. At its worst, it’s still a series with an incredible cast and a world so richly drawn it feels as though you could just wander right in. What are a few stumbles compared to that kind of promise? Grab some knitwear and a wee dram, forgive the missteps if you can, and allow all that possibility to unfold.