A 2009 story about a 12-year-old musical prodigy caught my eye today. His name is Jay Greenberg. He composes in his mind. It comes to him naturally. When we think of musical prodigies we imagine a child on a piano bench, or playing a violin. Not many compose. Greenburg has written five symphonies.

Sam Zyman, a composer who is Jay’s teacher at Julliard, told Rebecca Leung of CBS News: “We are talking about a prodigy of the level of the greatest prodigies in history when it comes to composition. I am talking about the likes of Mozart, and Mendelssohn, and Saint-Sans.

“This is an absolute fact. This is objective. This is not a subjective opinion. Jay could be sitting here, and he could be composing right now. He could finish a piano sonata before our eyes in probably 25 minutes. And it would be a great piece.”

One sentence in Leung’s story particularly struck me: “It’s as if the unconscious mind is giving orders at the speed of light,” says Jay. “You know, I mean, so I just hear it as if it were a smooth performance of a work that is already written, when it isn’t.”

I began to think in terms other than music. I began to think of the human mind. His mother Orna is quoted: “I think, around 2, when he started writing, and actually drawing instruments, we knew that he was fascinated with it. He managed to draw a cello and ask for a cello, and wrote the world cello. And I was surprised, because neither of us has anything to so with string instruments. And I didn’t expect him to know what it was.” When he was shown a miniature cello, his mom says, “He … started playing on it. And I was like, How do you know how to do this?“

Well, it was all in there, of course. Already there even at birth, perhaps. Already there in many of our minds. He was simply downloading it.

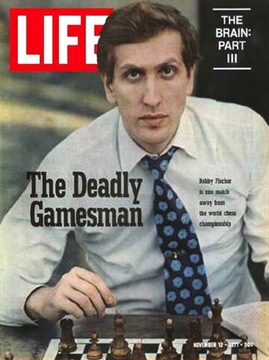

It is said that child prodigies are most often found in three areas: Music, mathematics and chess. What these areas have in common is that they all involve abstract relationships. You need no life experience to master them. No emotions, indeed, except those generated in the act of exercising your abilities. No maturity. You don’t have to have been anywhere, or to have done anything.

It is true that some music seems to contain great emotional content. I’m not talking about musical forms with lyrics, because the moment words are involved, abstraction falls away and literal meaning enters. But the “Ode to Joy” sounds to most people, I imagine, as if it evokes–joyous feelings. Other music sounds sad, inspiring, chaotic, soothing. I’ve never been convinced, however, that music tells a story. Without its title, would the “Grand Canyon Suite” be about the Grand Canyon?

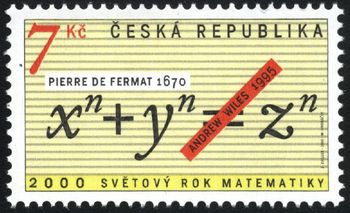

People who know chess well enough to understand it say that some of the best games of grandmasters move them almost to tears. Very well, but they are moved not by emotion but by witnessing an exercise of implacable logic, ideally without a single move that could have been improved upon. Similarly, in the field of mathematics, great was the satisfaction in 1995 when Fermat’s Last Theorem was proved after 358 years. But to solve it you need never have kissed anyone, loved a dog, read Hamlet or eaten a slice of apple pie.

Nor need Beethoven have done any of those things to write a Beethoven symphony. It is a Beethoven symphony all the same, and attains a kind of perfection in the abstract, regardless of how it is performed, or for whom, or where.

Following this line of reasoning, it occurred to me that this perfection preexists in the human mind. Just as Noam Chomsky once speculated that the rules of linguistics were hard-wired into the mind and not learned, so perhaps music, math and chess live there–and countless other forms that have yet to find an avatar in the practical world. A piano sonata doesn’t require a piano. The piano is simply the means through which its idea is expressed. I can imagine a world in which none of our present instruments existed, and in which an entirely different orchestra could be assembled. In my undergraduate years at the University of Illinois the avant garde musician Harry Partch staged concerts with instruments of his own invention. I was too callow to understand what I was listening to, but I recall it sounded like…music.

It may be that among the countless cells in our brains a process of arrangement and simplification goes on, by which these cells find more and more satisfactory ways to–Communicate? Align? Organize? If they were a random arrangement, could they even “think?” Perhaps our human brain cells have been continuously improving their lines of communication for thousands of years, and that by Darwinian evolution more efficient lines have been tested, and prevailed. It may be that Jay Greenberg is unique, but I think it just as likely that he is simply drawing on access to abilities many of us were born with but have lost track of. Are we born with a vast command of abstract logic, and lose it in the distraction of incoming noise? How possible is it to concentrate on the variations of the Ruy Lopez when our little ears are being hammered with coos and sweetness?

Chess, of course, would not exist without 64 squares and 16 pieces and a set of rules. The game is a way to negotiate infinity by the application of logic. Well, not infinity of course, but beginning with the “Shannon number” of possible positions, which is 10 to the power of 43, a Dutch computer scientist named Victor estimated (says Wikipedia) “the game-tree complexity to be at least 10 to the 123rd, based on an average branching factor of 35 and an average game length of 80. As a comparison, the number of atoms in the observable universe, to which it is often compared, is estimated to be between 4×10 to the 79th, and 10 to the 81st.”

So chess has considerably more possibilities than the number of atoms in the universe, which is as close to infinity as we can hope to approach in our lifetimes. The rules of chess create a means to negotiate those possibilities more efficiently than your opponent.

I thank those of you who are still with me. I have heard of small children who instantly grasp the rules of chess. I know many adults who remain resistant to them. They are not “necessary,” in the sense that chess itself is not necessary, but they involve access to those places in the brain that master such things.

In many arts and other fields, we hear of Being in the Zone. Gifted practitioners in those fields speak of Going with the Flow, and I think they’re referring to access to greater powers of their minds. They get out of their own way. They don’t “think too much.” Their minds are way ahead of them, and have it all figured out.

When I try to describe the way I write, I say it is “taking dictation from that place in my mind that tells me what to say.” This doesn’t make me a genius. It has nothing to do with that. It simply means that having been given language and grammar, my mind supplies the words. The moment I began reading about Jay Greenberg, this piece began writing itself, and all I had to do was type it out. Your field may not be writing, but in whatever you do, I suspect there may be an area in which your mind is composing and performs for you if you only listen.