For an hour before bedtime every night for a week, I’ve watched an episode of “Downton Abbey.” Last night the Earl of Grantham interrupted a garden party to announce the beginning of World War I, and I pulled up short. I was watching the first season via Netflix Instant, and inattentively failed to notice there were only seven episodes. I naturally expected ten.

I’m not one of those people who follows every series on Masterpiece Theater, HBO or whatever. There’s always a movie to be seen. The last series I watched completely was “Brideshead Revisited,” and before that all the way back to “Upstairs, Downstairs.” As you know, I’m an Anglophile. I seem particularly drawn to the era of English Country Houses before the First War, and to a degree between the two wars.

Someone wrote that country house life in peacetime was the apogee of human civilization. Could have been Orwell. Or probably couldn’t have. The point as I recall is that the Upstairs and Downstairs people were equally happy in their own ways. There was a stable hierarchy and everyone knew their place. “Knowing your place” is a term often used in connection with someone who tries to rise above it, but there’s also such a thing as possessing and valuing your place. There is pride in doing one’s job well, in being the epitome of a footman, a ladies’ maid, a butler, a valet, or an Earl. In Downton Abbey, I think it possible that the happiest people may be Carson the butler and Patmore the cook–and upstairs, the Earl and his wife Countess Cora. They are happy because they do their jobs well and are loyal and helpful to those who depend on them.

The most admirable man, up or down, is Bates, the Earl’s valet, but he is far from being the happiest. He has too active a conscience. In early life he went to prison to protect his worthless wife. Now he would rather be fired than cost another man his job–even if that man is the vile Thomas Barrow, who has lied about him and tried to frame him. Bates adds considerably to the entertainment value of “Downton Abbey” by enlisting our deep sympathy, but there comes a time when defending your own honor ranks above protecting the job of a villain. Remember, too, that Bates has had to undergo alcoholism and being a “cripple,” as everyone cheerfully describes him. Indeed, he almost got fired the first time because the loathsome Mrs. O’Brien tripped him at an embarrassing moment.

There is nothing Politically Correct about “Downton Abbey.” Thomas is not only a liar and a thief, but a deceiver of young women, an aggressive homosexual, and a chain smoker. He teams up with her ladyship’s maid, Mrs. O’Brien, to share smokes and plot against Bates. Meanwhile, Daisy the little scullery maid, even lies for Thomas because, poor thing, she thinks she may have a chance with him. The Cook knows better about her hopes for romance: “He ain’t a ladies’ man.” The view of homosexuality in the series is decidedly dated, but as a character Thomas functions admirably. There is sly humor in the way the only two characters who smoke very much are the villains.

I gather there is more humor to come in Season Two, and that I will regret, because although my politics are liberal my tastes in fiction respond to the conservative stability of the Downton world. The more seriously I can take it, the better I will like it. To be sure, there is monstrous unfairness in the British class system, and one of the series themes is income inequality. What must be observed, however, is that all the players agree to play by the same rules. In modern America the rich jump through every loophole in the tax code. But look what happened in the first episode of “Downton Abbey.” The Earl’s presumptive heir went down with the Titanic and the title passed to a distant cousin, Mr. Matthew Crawley of Manchester, who now stood to inherit the title, the house, the land and the money–including the personal fortune of Cora, the Earl’s wife. So deeply are the principles of inheritance embedded in the Crawley family that the earl seems staunchly prepared to give up his earthly possessions and be courteous in the process.

Of course the injustices of the class system work better in fiction than in life, because in fiction we all identify with the rich and powerful. Even in reports of reincarnation, people tend toward having been Henry V in an earlier life, and not a scabby footpad. In “Downton Abbey,” I identify with Carson. It is the liberal Mr. Crawley whose ideas are closest to my own, but the judicious and wise Carson who I envy.

There is nothing in my own early life that explains why I’m such an Anglophile. Maybe it can be traced back to the day Mr. Willis, my mother’s boss at the Allied Finance Company, went to England and brought me back the Coronation Number of Punch, with its photos of the new Queen and Buckingham Palace and Prince Charles, who was about my age. I could have been Prince Charles, if my mother had been the Queen. Think about it. Then my Classics Illustrated comic books led to novels, until I was deep into Dickens and then Trollope and all the others. In London during the Blitz there was a sudden surge of popularity for Trollope’s novels. There’s nothing like Nazi buzz-bombs whistling overhead to focus your attention on the intrigues of Barsetshire.

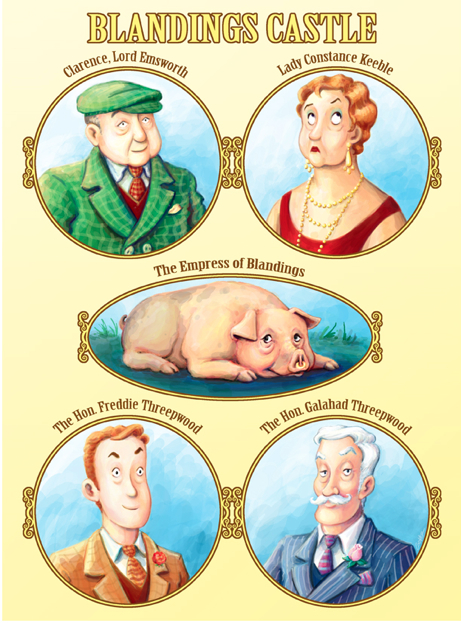

Even my love of Indian fiction may be connected; at the Calcutta Film Festival, an Indian critic explained to me why P. G. Wodehouse is the most popular English-language novelist in India: “Both nations are class-conscious, love wearing the proper uniform at every moment, are obsessed with family, are devoted to ceremony, cultivate mustaches, and prize eccentricity.” He may have had a point. Of all of Wodehouse’s novels, my favorites are those about Blandings Castle, its Lord Emsworth, and the Lord’s trusted Pig Man, George Cyril Wellbeloved, to whom is entrusted the care of the Lord’s prized pig , the Empress of Blandings. In Blandings an enchanted world exists in which everyone is innocent, even a pig thief.

But I stray. Watching “Downton Abbey” gave me a sense of deep comfort. With the Earl and his household I valued the great Yorkshire structure and its traditions. For an hour a night, it was mine. Yes, in the embrace of these ancient yellow stones and rich woods, the footsteps of countless ancestors had fallen. It mattered not if I swept the entrance or stood in it to welcome the Queen, I was there through the generations.

I could understand why the Earl he had devoted his life to its maintenance. I could even understand why he was so determined to give up the title and his fortune on the sake of principle; if you live under laws by which can lose everything when a ship goes down, then perhaps it’s not quite so unfair that you have it in the first place. You didn’t rob or steal to gain your possessions (although your ancestors may have). You were born into them. And with a blow from a lucky iceberg, a poor man in Manchester might find that he, too, was rich by the accident of birth.

In the meantime, life goes on at Downton. Marriages are arranged and rearranged. Kitchen maids get crushes. Ladies’ maids dream of mastering the typewriter and entering the prewar dot.com world. Grandmothers sternly defend ancient values and are willing to abandon them for benefit of family. A great machine like this country house can sail on through the centuries, its course not thrown off by the occasional discovery of a dead Turkish diplomat in the wrong bedroom. I am certain the snuff box will turn up eventually, and as confident as Carson is that Bates had nothing to do with it.

Season One is streaming free on Amazon Instant for Prime Members, or $1.99 per episode for others. It is also on Netflix Instant. Season Two is now playing on Sunday nights on PBS Masterpiece Theater.

The delightful art below is by Colleen Coover, who has the uncanny ability to look into my mind and draw exactly how I imagine everyone at Blandings, including the Empress.

The sketch of Chatsworth House is by moi, drawn on a sun-dappled afternoon.