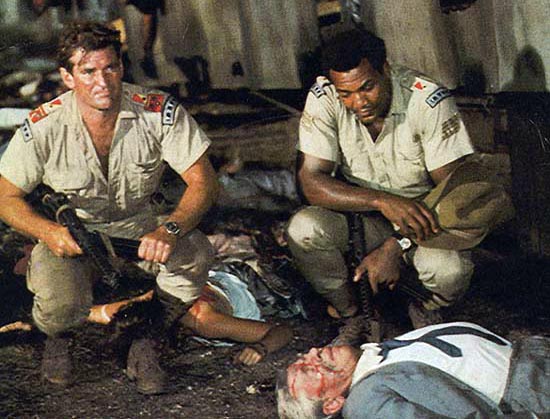

Just over a week ago, “Dark of the Sun” opened in Chicago. I wasn’t in town at the time and haven’t yet seen it. Glenna Syse reviewed it for The Sun-Times and found it a “nauseous exercise in new ways of drawing blood.”

It is impossible to know, she wrote, whether violence on the screen inspires violence in real life, “but the violence of our times is no excuse for the exploitation of excess in this film.” Why does Hollywood take the risk, she asked, of inspiring violence by, filming it and selling it as “entertainment”?

Less than a week after these words appeared, Robert Kennedy lay unconscious in Los Angeles. The unanswerable questions that Mrs. Syse asked have taken on a terrible urgency.

I have no way of knowing whether violence is more common in films today, but it seems to have become more explicit and brutal. Even more disturbing is the new attitude toward violence in many films. No longer is violence exclusively a force of evil. Now it is tolerated as a means toward good ends as well. “The Dirty Dozen” are possibly the most inhuman, monstrous soldiers ever shown on the screen. They are on our side.

This is an important distinction, I think. Violence in the movies is neither good nor bad in itself. No subject matter can be judged apart from its context. What matters is how violence is presented — whether it is seen as lawless and futile, or whether it is seen as legitimate.

Our belief in America has always been that tolerance is necessary to make democracy work. A losing political party does not go to the barricades but prepares for the next election. In theory, our political institutions reflect majority opinion and protect minority rights, and violence and anarchy are not necessary. But during this period in American history, that theory seems to be standing trial. A great many Americans no longer seem to believe in it.

This disbelief is reflected in many current American films, and violence is suggested as the natural alternative. This is the week when schools dismiss their students for the summer. In anticipation of the increased attendance by young people, several motorcycle gang pictures have been put into release. These are thought to be especially popular with teenagers. In all these pictures, gangs resembling the Hells Angels demonstrate their scorn for organized society and imply that self-respect is possible only when differences are settled on a personal or gang level, through violence.

In “Born Losers,” a film released some months ago, the hero dared to stand up against a motorcycle gang and declare himself in favor of law. For his pains, he was brutally beaten. The police forces were shown as intimidated by the neo-fascist tactics of the gangs; they refused to come to the hero’s rescue.

The most popular movie in the Loop right now is “Wild in the Streets,” in which a group of young people take over the government. They are described as “swingers.” In fact, they are fascists. After they gain control of the government, they put all citizens over the age of 30 in concentration camps and administer drugs that lobotomize them.

It may be easy for most of us to dismiss these films. In reviewing “Wild in the Street,” I called it silly. But the fact remains that it has found enormous popularity among the young people of Chicago. The theater is usually packed. The audience cheers and applauds. Twenty-five years after the Nazi concentration camps, great numbers of Chicago young people, most of them currently students in our public and parochial schools, having studied history and civics, are cheering fascism. I doubt that they even realize it.

“Wild in the Streets” is, in fact, opposed to the fascist takeover it portrays. The audiences don’t seem to understand that. There is something terribly disturbing in the way teen-age audiences have misinterpreted this film: They are cheering intolerance, they are applauding the most appalling violations of civil liberty, and they seem to have no inkling that their attitudes are barbaric.

It is necessary, however, to draw a distinction between films of this sort and other films in which violence is present. Because it was so enormously popular, “Bonnie and Clyde” has borne the brunt of attacks against violence in films. It is the wrong target. Of all the “violent” films of recent years, it is perhaps the only one that fully understands violence, understands its place in American life and makes a relevant statement about it. “Bonnie and Clyde” is actually a commentary on other violent films. It is an examination of the way in which the mass media glorify violence, folklore romanticizes it and culturally bankrupt, politically isolated Americans turn to it as a means of self-expression.

And that is where any examination of violence in movies should eventually lead: to the audience for it. Where have these people come from, these strange people who care nothing for democracy, who cheer cruelty, who spread the word from one to another that the newest motorcycle gang picture is a “good” one? For them, violence has replaced sex as the big box-office draw.

Perhaps they are products of the intolerance that seems to be spreading in great parts of our society. We have recently seen “homeowners” spitting at Negro children going into public schools. We have seen assassination become a risk of American politicallife. We have seen the arrogance of students who ransacked a professor’s office and destroyed his files because they disagreed with his political beliefs. Intolerance is epidemic in America today.

Perhaps it is not the movies, then, but their audience that should concern us. In a different sort of society, movies displaying neo-fascist violence might not be popular. They do very little business in Britain, but they are popular here. And they are a fairly recent phenomenon; indeed, the current cult of violence in movies is hardly two years old.

“Apparently the audience existed before the movies came along to serve it. The first motorcycle picture, “The Wild Angels,” was made almost absentmindedly. Its producers were shocked to discover what an enormous success they had on their hands. Something in American Society, perhaps the intolerance that so many citizens feel for those with different opinions, had already prepared an audience for this kind of violent film.

The movies, after all, are a small part of our national life, and they usually follow public opinion instead of leading it. Motion picture producers are among the most conservative animals on earth. Before they invest hundreds of thousands of dollars in a film, they have to be satisfied that a substantial market exists for it. If we were to take violence out of movies, would we take it out of our society at the same time? It is symptom, but not the disease.

It may be, however, that the misuse of violence in films has now come full circle. Originally the children of violence in our society, these films may now be perpetuating and reinforcing it. I have no way of knowing if this is the case. But it seems possible.

If so, censorship of violence in films is not the answer; censorship can never be an answer in a free society. But producers, distributors and exhibitors are not obligated to traffic in violent films simply because there seems to be a market for them.

Thoughtful members of the motion picture industry might well ask themselves, in this time of national grief, whether self-restraint in the exploitation of violence is not necessary.