My Answer Man received a question asking if crime expert Jay Robert Nash still holds the theory that John Dillinger was not killed by the FBI in front of the Biograph Theater on July 24, 1934. He does. Nash informs me he stands behind his two books on the subject, and may have met the real Dillinger many years later. RE

by Jay Robert Nash

Will there never be an end to this? Probably not, since the FBI (and no one else) has ever refuted the FACTS (far beyond my theory) I presented in several books about the shooting at the Biograph Theater on July 22, 1934.

It was not out of Melvin Purvis’ grandiosity, but his expediency to appease J. Edgar Hoover’s grandiosity, that Purvis, the FBI agent in charge that night in Chicago, allowed the wrong man to be killed. You must know how all this worked in those days. When Hoover took over the Bureau in 1924, replacing William Burns, the Bureau was a corrupt instrument of the Harding administration, with FBI agents like Gaston Bullock Means conducting widespread blackmail and extortion from a corner office in the Bureau and Hoover had a hell of a time getting rid of Means and others. When he did, he instituted absolute control over the Bureau in that all agents had to report directly to him from all field offices. No major federal case was closed until he, Hoover, closed it, and he did not do that until hereviewed each and every DAILY report from all FBI agents in charge of all areas.

Hoover personally announced or personally approved of all press announcements on all cases. He totally controlled the public mouth and words of the FBI. To build the image of an invincible Bureau, Hoover relentlessly spent much of his time controlling that public image and manipulating the press-newspapers and radio in those days. He cheated and lied to build that FBI reputation, such as creating out of whole cloth the image and actual words of the “G-Man”; for instance, he issued a statement and reiterated that statement later on in an article for the American Legion magazine that FBI agents captured George “Machine Gun” Kelly in a rooming house and when they burst through the door of his room, Kelly, according to Hoover, stood quaking in his underwear, pleading: “Don’t shoot, G-Men, don’t shoot!” This was a lie. Kelly was captured by Memphis, Tennessee police detective sergeant William Raney, who slipped into Kelly’s bedroom on the night of September 26, 1933, put an automatic to the kidnapper’s head and awoke him with a nudge of that cold instrument. Kelly awoke and said: “Well, I’ve been expecting you fellows.” Raney marched him down to Memphis police headquarters where he was booked and then turned over the FBI agents who were waiting at those headquarters-none were present when Kelly was captured and Kelly never said “G-Man” to them or anyone else. That was Hoover’s invention. He knew that only local police had the authority to make official arrests before suspects were turned over to his agents to face federal charges–in Kelly’s case a kidnapping charge.

The only federal charge ever made against Dillinger was that he drove a stolen car across a state line (the sheriff’s car he stole when making his escape from the jail at Crown Point, Indiana and driving it into Illinois), and it was upon that charge alone that Hoover made Dillinger Public Enemy Number One-simply because he was getting more publicity in 1934 than was Hoover and his FBI. For instance, when Dillinger robbed the bank at Greencastle, Indiana, he noticed a farmer standing in front of a teller holding some cash. “Is that your money or the bank’s,” he asked the farmer. The farmer said it was his life savings and that he had just drawn it out. Dillinger, a farm boy from the flatlands of Indiana, said: “Put it in your pocket.” (This documented event was later wrongly attributed to those two snakes Bonnie and Clyde, and appears in that 1968 movie about them and which you, Roger, became one of its first champions).

When the newly-elected FDR read about the Greencastle story, he called Hoover and said: “This man Dillinger is becoming a national hero, a Robin Hood. The press is showing him standing up to the banks that they believe have failed the country. You had better do something about this man, Edgar.” Every time the publicity conscious FDR read another story about Dillinger-and that was almost every day-he called Hoover, asking: “What are you doing about this man?”

Desperate, Hoover latched onto the stolen car event and labeled Dillinger Public Enemy Number One so he could concentrate his forces on him. He pressured Melvin Purvis, chief of his Chicago office every day to “get Dillinger and get him quick!” In April 1934, Purvis got a tip that Dillinger and his gang were holed up in a lodge in Manitowish Waters, Wisconsin and Purvis gathered every agent in the area, flying with them to that lodge, driving through back roads in the middle of the night to get there. The lodge was not officially open, except for its bar which was patronized by local residents and WPA and CCC laborers working in the area.

What Purvis did that night set in motion what later happened at the Biograph Theater three months later. He was on the spot. His boss, Hoover, had told him to either get Dillinger or resign.

With twenty some agents, recently authorized to carry weapons and make arrests without local authority, Purvis and his men spread out in front of Little Bohemia Lodge, which has considerable frontage (I know, have been there several times), and slowly advanced in the darkness toward the place, where lights were showing on the ground floor. They took up positions behind trees and waited. At that time, two reporters, who had heard about the agents flying into the area, followed them to the lodge and waited in thick brush just behind where the agents were positioned. They watched as three men emerged from the lodge and slowly went to a car, getting in. Just as the engine started and the lights turned on-the car was facing in the direction of the agents-the lights flooded the area to show the agents. One of them-it may have been the impetuous and sleepless Purvis-shouted: “They are getting away! Let them have it!”

All hell broke loose-the agents firing submachine guns, BARs, rifles, pistols and automatics. That car was shot to pieces, riddled by at least two hundred bullets. Then the lights in the lodge went out and the agents started firing into the lodge, shooting out the windows on the first and second floors. Neither Purvis nor any other agent ever announced their presence or demanded anyone to come out and surrender.

Purvis and some of his men then ran up to the riddled car and pulled open the doors. Two badly wounded men fell out. Behind the wheel, his face almost shot away and dead, was a third man. The two reporters then ran up to the car-I talked several times to one of them many years later-and began swearing. “You dumb bastards!” one reporter said. “You just shot three of our boys-they’re CCC workers-and you killed Gene Boiseneau!”

“Oh, my God,” Purvis said, then turned and shouted to his agents to stop firing at the lodge, but this did not happen for several minutes. By that time, Dillinger, John Hamilton, Tommy Carroll and others in the gang, who had never fired a shot-there was no “battle”-went out the second floor back windows of the lodge, dropping to earth from a low roof and then ran along the shore of the lake in the darkness and all escaped. The gang began running as soon as Purvis and his men opened up on the CCC workers.

One of the reporters took a picture of the shot up workers and Purvis grabbed the camera and removed the film, but the other got a photo of their shot up car (and gave me that photo to me years later).

Purvis’ FBI raid at Little Bohemia was a disaster. An innocent man had been killed and two other innocent men badly wounded by a bunch of trigger-happy FBI agents led by one of the most irresponsible men in FBI history, who had been pressured into his rash actions by his boss, Hoover. The reporters broke the story and Hoover’s Washington critics, chiefly Senator McKellar, jumped all over it-publicly denouncing Hoover, Purvis and their FBI agents as a bunch of gun-happy goons, and demanding that they all resign.

Hoover exploded, telling Purvis that if he did not capture Dillinger quickly, he would personally preside at Purvis’ public crucifixion. It is not so strange then, with his career on the line, that Purvis did what he did. In early July, Purvis was approached by Sergeant Martin Zarkovich, a crooked cop with the East Chicago, Indiana Police Department (whom I met three decades later and who had a strong inclination to shoot me). Zarkovich said that he had a slight acquaintance with a brothel madam named Anna Sage (a lie-she had been his mistress for years and he had protected her bordello operations in Lake County Indiana for years until she became so notorious that he had to move her operation to Chicago).

Zarkovich told Purvis that Sage told him that one of her girls, Polly Hamilton (no relationship to John Hamilton, one of Dillinger’s bank robbing associates) was seeing a man she thought was Dillinger. Zarkovich told Purvis that he could arrange for him to talk with Sage about it, if he liked. Purvis asked Zarkovich why he was doing all this and Zarkovich said that he wanted to get Dillinger because Dillinger had killed a good friend of his, a police officer in Gary, Indiana, during a recent bank robbery there (another lie, Dillinger did not rob that bank and Zarkovich had no friend on that force, where he was known to be associated with underworld bosses). Zarkovich said that, in return for setting up Dillinger, he wanted Purvis’ promise that he, Zarkovich, would be the ONLY person to shoot and kill Dillinger, but that the FBI could have all the credit for it. That way his revenge for the death of his friend would be satisfied.

Purvis bought that story and met with Sage, who was to become the notorious Woman in Red (her skirt was actually orange on the night of the shooting) a few nights later in Lincoln Park. Purvis walked to a car in which she was sitting (directed to that car by Zarkovich) and there she told him that she thought that the man seeing her girl, Polly, was Dillinger. Purvis blindly accepted that “make” without him ever making his own identification of that man. She told Purvis that they would be going to the movies soon and she would call him at his office to let him know which theater they would attend. She called two day later (much of this was recorded by Purvis’ secretary, who I talked with years later) to tell Purvis that she, Polly, and “her man” would be going that night, July 22, 1934, to either the Marlboro or Biograph Theaters-the “man” had not made up his mind about which film to see. This was ridiculous in hindsight, but Purvis never bothered to check what was showing at those two theaters that night-the Biograph was showing a Clark Gable film, Manhattan Melodrama, and the Marlboro a Shirley Temple film.

There was, of course, a very good reason to give Purvis this story. ONLY Purvis and Zarkovich knew what Anna Sage looked like-Zarkovich had taken pains to make sure that Purvis met with Anna Sage only once and alone in Lincoln Park-and she was the one through which the FBI would make their identification of Public Enemy Number One, since they had never even seen the man she and Polly would be bringing with them to that movie! “All right,” Zarkovich told Purvis, “I will go to the Marlboro with some of your agents and wait there. If she shows up, we’ll let them go into the theater and call you to come over with your other agents and I will shoot him when he comes out of that theater. You go to the Biograph and if they show up there, you call me and wait until I get there and I will shoot him when he comes out of that theater.” The hitch was that Zarkovich knew that Anna Sage, Polly Hamilton and “James Lawrence” were going to the Biograph all along. He wanted Purvis to take responsibility of identifying Anna Sage and the man she would show up with, making it therefore an FBI identification and all responsibility for whatever happened thereafter exclusively that of the FBI and, specifically, Melvin Purvis.

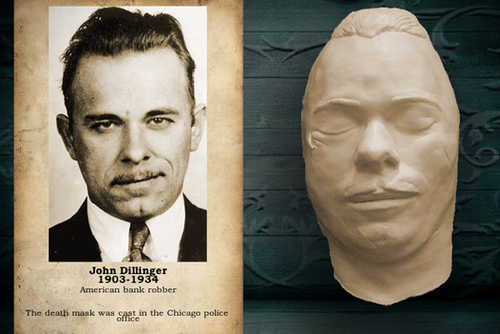

That’s exactly what happened. Sage, Hamilton and their “man” showed up at the Biograph, and this WAS THE FIRST TIME Purvis or anyone in the FBI ever saw that man-when he arrived at the theater and went inside-and it was then that Purvis kept his promise to Zarkovich and had him come to the Biograph from the Marlboro. Zarkovich waited down the street in a darkened store entrance. Purvis stood outside the theater with a cigar in his mouth and, when he saw Sage, Hamilton and their “man” leave the theater at about 10:20 p.m., he lit that cigar, which was his prearranged signal to Zarkovich that the trio were approaching him. When they passed him, the women saw Zarkovich and dropped back. He simply walked up behind the man, pushed him down to the cement and fired two bullets into the back of his head (proved by the autopsy), murdering him at close range, then walked away and Purvis and his agents rushed to the scene. A crowd assembled and Purvis used his foot to roll over the body of the dead man, his face to the cement. When he saw that face, Purvis gasped and blurted to himself (but heard by several persons, including a reporter) “That doesn’t look like Dillinger.” He caught himself and immediately introduced what the FBI would later use to excuse the marked differences in the facial appearances of the dead man and John Dillinger: “Neat bit of plastic surgery, that!”

By that time, Purvis must have known that it was Little Bohemia all over again-another innocent man killed and his and Hoover’s careers down the drain. If he didn’t, he learned it from real authorities some few hours later when two physicians (top pathologists; I interviewed both of them) told him that the man killed outside the Biograph could not have been John Herbert Dillinger.

Purvis talked with Zarkovich about this and Zarkovich, acting as if amazed and that he himself had been duped by that conniving Anna Sage (sure) helped Purvis out by providing a planted fingerprint card with Dillinger’s prints on them (a Chicago Police Department fingerprint card no less, not an FBI card), which Purvis marked in his own handwriting “FBI” as if the prints had been taken by FBI agents of the dead man (none were ever taken as the physicians and the coroner’s people told me-and they were in charge of that body).

Meanwhile, Hoover was waiting for Purvis’ report and it did not come. He burned up the phone wires to Chicago in trying to reach his agent in charge. It was twenty some hours after the shooting that Purvis told Hoover on the phone that “there are some serious problems with the case” and that he was not sending in his report the usual way, but would personally bring it to Washington to deliver it to Hoover. Purvis, who had immediately and preemptively announced that the FBI had shot and killed Public Enemy Number One when standing with that body outside the Biograph Theater before a Chicago Police wagon (driven by a friend of Zarkovich’s) arrived to take the body to county morgue, had taken all the thunder from Hoover. Purvis, for the moment, not Hoover, was the hero of the hour-a very brief bitter hour, indeed.

Purvis arrived in Washington some days later and Hoover was waiting for him at the train station. The two of them were photographed together when they arrived that night at Bureau headquarters (I have one of those photos). When Purvis handed him his nine-page report, Hoover must have had apoplexy. It started with the following line: “This case contains discrepancies that we cannot explain and for which, no doubt, there will be serious ramifications.” This document no longer exists, to my knowledge, in the FBI files.

Of course, in my books, I pointed out many of those discrepancies–which were supported in the autopsy conducted by TWO top pathologists before a student class of more than twenty persons, with a recording nurse in attendance, documenting the statements of each physician, the first making an initial examination, the second checking what the first identified and reaffirming it to the recording nurse. There was NOTHING haphazard or slipshod about that autopsy since the physicians had already told Purvis that the corpse was most likely not that of John Dillinger. They recorded the eyes of the dead man as brown (Dillinger’s were blue or blue-gray); they found none of Dillinger’s well documented scars and bullet wounds; they took out the heart and closely examined it and determined that the dead man had had a rheumatic heart condition since childhood and was terminal close to the time of his being shot to death (Dillinger could never have played semi-professional baseball–as second baseman for the Martinsville, Indiana, team–or ever leaped over the six-foot partition cages in banks as he was routinely seen to do in his many bank robberies, with such a heart condition); the body was shorter and heavier than that of Dillinger, that he was prone when shot and had been executed (as accurately described through the path of the bullets outlined by the pathologists) and many more discrepancies in a autopsy that disappeared from the Coroner’s office the day it was filed. I obtained a copy of that autopsy through one of the pathologists that conducted it years later–he kept copies of that particular autopsy where he held on to none of the many thousands of others he conducted, knowing, as he said to me, that “I knew somebody would come along some day to dig into this story.”

While the autopsy was being conducted, James Henry “Blackie” Audett, a West Coast bank robber and one of the last Dillinger associates (who was paroled to my custody years later from a federal prison when terminally ill with cancer, and who gave me much background information no this case) went to a cabin in Aurora, Illinois and told a man waiting there: “Well, you’re dead now, John. Let’s get the hell out of here.” Audett had promised to take Dillinger West to Oregon to live with Indians on a reservation there Dillinger’s first girl friend, Evelyn “Billie” Frechette, was a Menominee Indian girl, but she had been captured and imprisoned and, according to Audett, “John wanted to meet another Indian girl and settled down with her, which is why I took him to that reservation in Oregon.”

Dillinger, according to Audett, refused to leave right away for the West Coast. He first wanted to make sure that he was not only dead, but securely underground in a way he could not be recovered and identified as another man. A few days after the body of the man shot at the Biograph Theater was buried at a cemetery in Indianapolis in the Dillinger plot, Dillinger’s father, John Wilson Dillinger appeared at the cemetery with several trucks, including a concrete truck and many workmen, telling the curator that he was worried that the body of his famous son might be stolen by ghouls or souvenir hunters. The curator knew that the senior Dillinger was broke and had not even been able to pay for the $50 embalming fee of the dead man, but he suddenly had enough wealth to pay for a dozen workmen, trucks, steel, iron, and a concrete mixing truck. The senior Dillinger had the corpse dug up and concrete mixed with metal, and wire poured in slabs below, above, at the sides and completely around the casket as it was reinterred. When interviewing the curator of that cemetery years later, he told me: “Get that body out of there and examine it? Impossible. You have to blast it out of there with dynamite and what would be left would not fill up a small cookie jar.”

I told that to Audett years later and he said: “That’s why John wanted that body buried that way. In fact, when that work crew drove into that cemetery to pour all that iron, steel and concrete around that dead guy, John and I were sitting in the back of one of the trucks, and we helped them do the job. So John buried himself, you see. Also, John had his name put on that tombstone to read John H. Dillinger, Jr. He wasn’t a ‘junior.’ There was no junior. His father’s name was John Wilson Dillinger. John had that “junior” put on as a way of a joke, that the man taking his place in that grave was a ‘junior’ his own.” That night Audett drove Dillinger west to Klamath Falls, Oregon, where he, indeed, did meet and marry an young Indian girl. Audett gave me a picture of both of them taken about 1948, which I employed in one of my books.

Who was the dead man? Anna Sage and Polly Hamilton only knew him as “James Lawrence,” who said he worked as clerk at the Commodities Exchange on LaSalle Street (no record of him there). He was not a well man, according to Audett, who claimed that he actually agreed for several thousand dollars to imply to Sage and Hamilton that he might be the infamous bank robber. He was nevertheless murdered by Zarkovich, who, according to Audett, was paid $10,000 or more to set up the wrong man by Dillinger, and that makes him, Dillinger and Audett and, most likely, Sage, parties to murder.

Martin Zarkovich, made sure that Polly Hamilton disappeared and Anna Sage was deported, undoubtedly with Hoover’s collusion as he by then wanted to get rid of everyone associated with the case, including Purvis, whom he fired the next year. Sage was murdered in Rumania some years later. Zarkovich got $5,000 of the overall federal reward for Dillinger’s capture, in addition to what he reportedly got from Dillinger. I believe Zarkovich got a copy of Purvis’ report to Hoover, and I believe that John Herbert Dillinger also got a copy of that report, both of these references coming from James Henry “Blackie” Audett, who, as stated above, was Dillinger’s liaison in this conspiracy.

John Edgar Hoover, self-styled Machiavellian prince, had been compromised for life by that report. His “ace” agent had killed an innocent man in April 1934 in the FBI’s frantic attempt to capture Dillinger, and the same “ace” did the same thing three months later in July 1934. By that incredible time, it was imperative to have John Dillinger remain dead–forever.

He could not, this dead man, bring himself to remain dead, however, and he began sending letters and his picture to several persons many years later, pointing out that the “wrong man” had been “shot outside the Biograph theater,” and it was one of those letters that fell into my hands and initiated my many years of research into the case and producing two full books on the subject. I should point out that one of those letters was sent to Melvin Purvis and, after he read it, he took out his old FBI service automatic, walked into his back yard, and blew out his brains.

Many years later, I interviewed Evelyn “Billie” Frechette (only one to ever have an interview with her) and she reaffirmed my suspicions in the case, and the fact that Audrey Dillinger was not Dillinger’s sister, but his mother, and that is why Audrey supplied a phony identification of the dead man so that she could protect her son. When I interviewed Zarkovich, he became suspicious of my questions, then outright challenged me–he stood up, about six feet five, unbuttoning his pistol holster and holding his hand on the butt of the gun–saying: “Are you telling me something’s wrong here? That I did something wrong?”

“Oh, no,” I replied, “other than arranging a conspiracy and executing an innocent man, not a bit.”

“Get the hell out of here!” he shouted. I got out.

There were dozens of other people I interviewed in covering that story, including Russell Clark, the last of the Dillinger gang released from prison (like Audett, dying of cancer). I interviewed him in a seedy hotel room in Indianapolis–he had then been in touch with Audrey Dillinger, who lived in the area. He already knew about my story on Dillinger and when I asked him where Dillinger might be living, he said, “You seem to know everything else, how come you don’t know that?”

“Should we try southern California?” I said.

“Why there?” he asked, dropping his cocky attitude.

“Why does Audrey Dillinger frequently go out there–she has no relatives living in California.”

Then Clark blurted: “Go to Puente, wise guy. You got the guts for everything else, why not that?”

Clark died a short time later. Why he gave me the name Puente, California, I do not know, but I went there and met a man who talked to me while we both stood in a dark room. I do not know for certain that the man I talked to was John Dillinger or not. From what he said I though then and do now that he could have been that man. If that was the case, however, it was not my obligation to inform anyone about it, for, according to the FBI, John Herbert Dillinger had been dead since July 22, 1934. The world bought Hoover’s story and it is welcome to it. I told my story, and the world is welcome to that, too.

PS: Johnny Depp as John Dillinger? What a joke. The producers of that film would have been better served if Moe Howard was still alive and had been cast in that role–he would have been far more entertaining!

Twenty-nine books on Amazon’s Jay Robert Nash page:

http://budurl.com/563r