The following article was originally published on May 17th, 2010.

When I began as a film critic, Jean-Luc Godard was widely thought to have reinvented the cinema with “Breathless” (1960). Now he is almost 80 and has made what is said to be his last film, and he’s still at the job, reinventing. If only he had stopped while he was ahead. That would have been sometime in the 1970s. Maybe the 1980s. For sure, the 1990s. Without a doubt, before he made his Cannes entry, “Film Socialisme.”

The thousands of seats in the Auditorium Debussy were jammed, and many were turned away. We lucky ones sat in devout attention to this film, such is the spell Godard still casts. There is an abiding belief that he has something radical and new to tell us. It is doubtful that anyone else could have made this film and found an audience for it.

He shows us a series of shots from a cruise ship traveling the Mediterranean, and also shots which travel through human history, which for the film’s purposes involve Egypt, Greece, Palestine, Odessa (notably its steps), Naples, Barcelona, Tunisia and other ports. Then we see fragments of a story involving two women (one a TV cameraman) and a family living at a roadside garage. A mule and a llama also live at the garage. There are shots of kittens, obscurely linked to the Egyptians, as well as parrots. The cruise ship is perhaps a metaphor for our human voyage through time. The garage is anybody’s guess.

There is also much topical footage, both moving and still. Words are spoken, some of them bits of language from eminent authors. These words appear in widely-spaced all-uppercase subtitles, and are mostly nouns. My impression, with imperfect French, is that some of the spoken wordage might be comprehensible. The subtitles, Godard has explained, are deliberately in what he calls Navaho English, which is a good deal like American French (“You…give…food?”)

The words and images add up to an incoherent mosaic involving socialism, gambling, nationalism, Hitler, Stalin, art, Islam, women, Jews, Hollywood, war and other large topics. I confess I have no idea what meaning they’re intended to convey. I have not the slightest doubt it will all be explained by some of his defenders, or should I say disciples. Although a commenter on my blog recently made sarcastic remarks about such a shameless liberal as me basking on the Riviera and drinking in Godard’s socialism, there is nothing in the film to offend the most rabid Tea Party communicant, who would be hard-pressed to say what, if anything, the film has to say about socialism.

As I was watching it, my mind wrote down a possible opening sentence for this notice: “Jean-Luc Godard’s new film is about what you think about when you watch it.” All films fit that definition, but some fit it better than others, and “Film Socialisme” fits it best of all. Godard depends on us to do the heavy lifting. Some people are fond of saying, “Let me just put an idea into your head.” Godard has sent my mind scurrying between ancient history and the modern entertainment industries, via Marxism and Nazism, to ponder–well, everything.

I think it’s probable that a French-speaker would obtain more from the film (which also contains several other languages), but I must console myself that the titles will be in English everywhere and for all audiences. Godard has provided an excellent jumping-off point for whatever you want to conclude about anything, so long as you connect it somehow with the words “Godard” and “Godardian.”

“Film: Socialisme” is very good looking. Apparently, in addition to standard digital video, Godard used a state-of-the-art iteration of high-def video; some shots, especially aboard the cruise ship, are so beautiful and glossy they could be an advertisement for something, perhaps a cruise ship.

The film closes with large block letters: NO COMMENT. It ended, and I looked forward to attending Godard’s press conference. I have seen him before at Cannes, after more explicable films, and once at Montreal I sat next to him at a little dinner for film critics, at which he arranged his garden peas into geometric forms on his plate and told us, “Cinema is the train. It is not the station.” Or perhaps my memory is tricking me, and he said, “Cinema is the station. It is not the train.” Both are equally true.

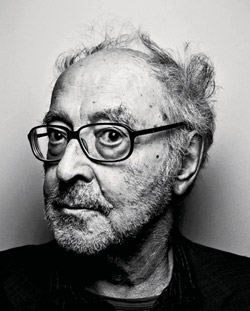

Todd McCarthy (above) was standing in the row behind us, still scrutinizing the credits, and said he’d heard that Godard had canceled his press conference. Todd often receives such intelligence, perhaps by telepathy, during screenings. But he didn’t believe it. We agreed to go check it out, just on the odd chance. One would feel such a fool for having missed Godard’s last press conference at Cannes.

Peter Howell, the film critic of the Toronto Star, tall as an NBA forward, was already in a crowd of perhaps 100 outside the press conference room. These hopefuls had turned up on the off chance of Godard changing his mind. With Godard, you never know. Word went around that Godard would hold the press conference after all, and had canceled it only in order to make a statement. A helpful festival guard said he knew nothing. From no other director is such behavior expected, or accepted. Then another guard told us that Godard would definitely not be holding a press conference.

So perhaps that was consistent with NO COMMENT, and by turning up for the cancelled conference anyway, we had learned/observed/refuted/proven the point. That Godard, what a card. Still cute at 80.

The following trailer for the film, dated in the summer of 2009, is described on YouTube as “with English subtitles.” They are not, however, subtitles that reflect the appearance or content of the English subtitles in the movie. The words “Islam is the East’s West,” for example, nowhere appear.

•

Now here is a shorter trailer, posted in March 2010, that is more true to the look and style of “Film Socialisme.” It looks very much to me like the film itself on fast-forward. Well, Ken Russell once informed me at this very film festival that all films, including his own, look better on fast-forward.

•

Below: My sketch of Ken Russell at the Cannes 1987 press luncheon during which he insisted all films were improved by viewing them in fast-forward.

—