“Youth Without Youth” proves that Francis Ford Coppola can still make a movie, but not that he still knows how to choose his projects. The film is a sharp disappointment to those who have been waiting for 10 years since the master’s last film. The best that can be hoped is that, having made a film, Coppola has the taste again, and will go on to make many more, nothing like this.

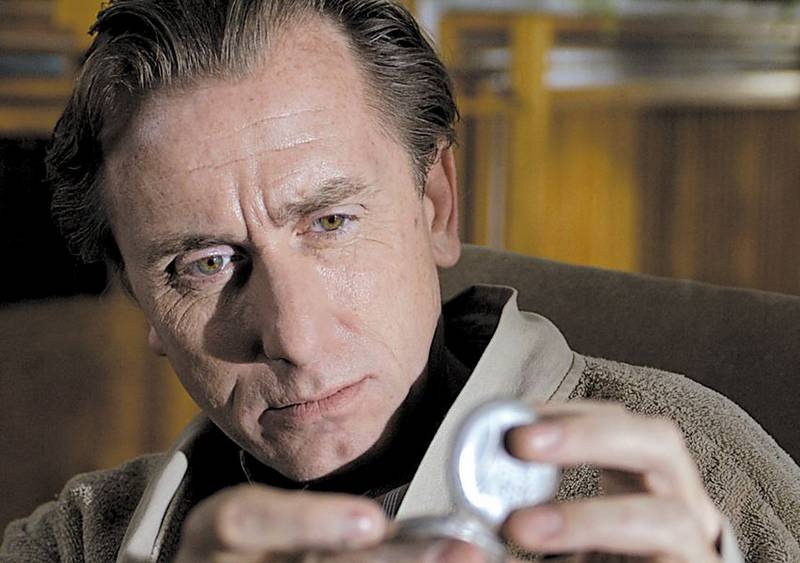

His story involves Dominic (Tim Roth), a 70-year-old Romanian linguist who fears he will die alone and with his life’s work unfinished, and decides to kill himself. Before he can do that, he is struck by a bolt of lightning that should have turned him into a steaming puddle, but instead lands him in a hospital, burned to a crisp. Then a peculiar process begins. He starts to grow younger. His hair thickens, and loses its gray. His rotten teeth are pushed out by new ones. His skin heals. His health returns.

It is the eve of World War II, and Dominic becomes of intense interest to the scientists of the Third Reich. Perhaps Hitler thinks his wounded soldiers can be made whole, or that he himself can turn back the march of time. Dominic, now hale and hearty, finds himself in Switzerland being seduced by a sexy German spy, when one day he sees, or thinks he sees, a woman on a mountain hike who resembles Laura, the lost love of his youth.

This is Veronica (Alexandra Maria Lara), who is, wouldn’t you know, struck by lightning and starts to grow older. In the process, she regresses backward in linguistic time, and begins speaking Sanskrit, Babylonian and perhaps even the Ur-language from which all others descended.

This is exciting beyond all measure to Dominic, who has researched the origins of language, but it is also heartbreaking, because he seems to have had his lost love restored to him, only to be taken away by the implacable advance of age.

Coppola found this story in a novella by the Romanian-born Mircea Eliade, for many years a scholar of religious history at the University of Chicago. It is possible to see how the movie might have been simplified and clarified into an entertainment along the lines of “Time After Time,” but Coppola seems to positively embrace the obscurity and impenetrability of the material.

There is such a thing as a complex film that rewards additional viewing and study, but “Youth Without Youth,” I am afraid, is no more than it seems: a confusing slog through metaphysical murkiness. That it is so handsomely photographed and mounted, and acted with conviction, only underlines the narrative confusion.

We know from interviews that the story means a great deal to Coppola, now at the same age as his protagonist. But his job is to make it mean a great deal to us. He is a great filmmaker, and I am sure this film is only a deep, shuddering breath before he makes another masterpiece.