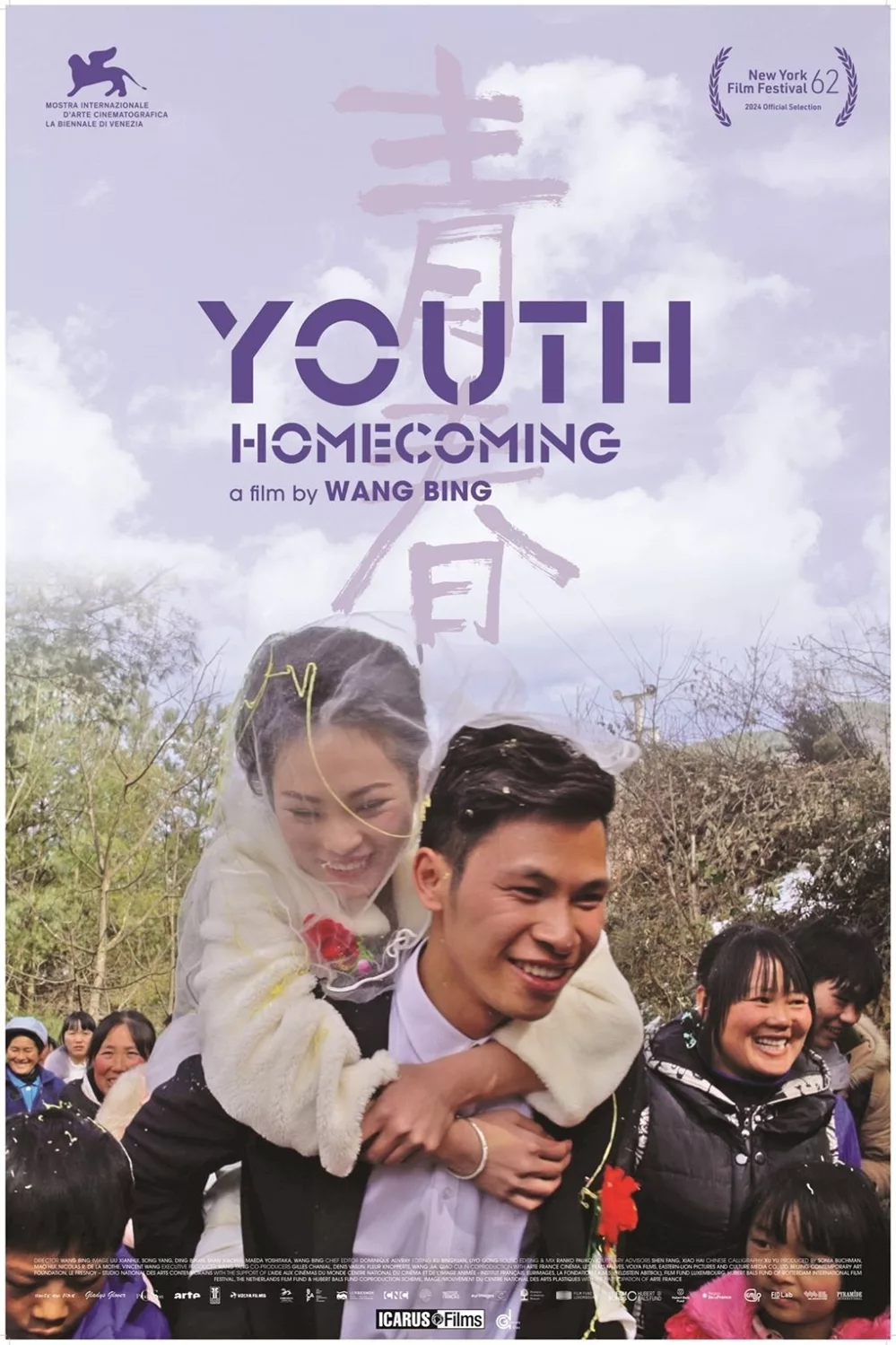

There are soft but noticeable limits to what can and can’t be expressed in “Youth (Homecoming),” the third of Chinese director Wang Bing’s three slice-of-life portraits of young textile workers in the Northern township of Zhili. Like many non-fiction filmmakers, Wang first has to give his footage some kind of shape, though in this case, it’s not a narrative. He and his editor Dominique Auvray shot dozens of Zhili’s workers over the course of five years (2015-2019) and, in that time, captured the precarious nature of their subjects’ lives through sentence fragments, pregnant pauses, and lots of non-verbal communication between migrant workers. In “Youth (Homecoming),” we also see some young people returning home to the outer provinces, where their work lives get recontextualized with a few standout domestic scenes, including a wedding and some Lunar New Year festivities.

Wang and Auvray’s task, to document Zhili’s laborers in a meaningful and respectful way, seems daunting, especially given how hard “Youth (Homecoming)” strains against the limits of what the movie’s skittish but curious subjects feel comfortable saying on camera. Zhili’s workshops are already physically confining and emotionally stifling, especially during work hours, but Wang and Auvray’s assignment became even harder given their timing. You can still find work in Zhili, but for much less pay, and while most of Zhili’s workers have limited options, they also have to make some fast decisions given their low earnings, high quotas, and shamefully withholding managers (several employees complain that their bosses owe them months of back wages).

“Youth (Homecoming”) sometimes feels more like an over-extended coda to Wang and Auvray’s trilogy, especially after the climactic “Youth (Hard Times),” the longest of the three “Youth” movies at almost four hours long, and the one with the most rising action and dramatic incidents. “Youth (Homecoming),” by contrast, gathers a lot of the themes and concerns of both that earlier movie and its predecessor, “Youth (Spring),” and wraps things up with an appropriately irresolute finale. “Youth (Homecoming)” may still be the richest of these three documentaries, given its deeper focus on romantic partners and family life. It’s also the most shapeless part of Wang and Auvray’s triptych and, therefore, the hardest to warm up to unless, of course, you’re already invested in the filmmakers’ essential project.

Dialogue tends to suggest more than it explains in the “Youth” trilogy, and that’s especially apparent in “Youth (Homecoming).” In an early scene, we hear a depressing phone call play out in real time—a young worker asks to be paid before he returns home; his manager doesn’t go for the idea—without actually hearing half of the conversation. The short but meaningful pauses that break up this conversation (whenever the manager replies) speak for themselves, just like several on-screen couples bicker and lean on each other as they trudge home or compare notes over their sewing machines.

One young man in his early twenties scoffs at a colleague after she tells him how many garments she could complete. Other couples disagree about quality control—“The boss says that they’re too loose.” “I say they’re tight!” “I say they’re loose!”—and work ethic: “You can’t even stitch straight, and we’re making bow ties!” These aren’t substantive conversations, but they provide a rich and (mostly) rewarding view of life in Zhili.

Wang and Auvray’s subjects may be largely in their early to late 20s, but some of them are veterans at their trade and have already experienced the worst that Zhili’s workshops have to offer. Then again, as viewers of “Youth (Spring)” remember, there’s still a persistent undercurrent of romance and flirtation throughout. You can sometimes hear the radio playing over the grind of sewing machines. While these Mando-pop songs’ lyrics aren’t exactly deep, they do express a sweet, naïve yearning for a future that can’t meaningfully be imagined or realized now. You watch “Youth (Homecoming)” to see young workers at play, old and new parents fussing over their own kids, and loosely paired couples drifting from one shop to the next. Furtive glances and hilariously off-the-cuff disagreements abound: “Marry a man with an education, they said. That’s you, right?” Most of these exchanges won’t leave viewers with a firm sense of closure.

If you’ve already seen “Youth (Spring) and “Youth (Hard Times)” (and you should), then you already understand the appeal of “Youth (Homecoming).” There’s so much detail and such a clear sense of dramatic proportion that it almost doesn’t matter that the movie doesn’t resolve itself traditionally or with a full stop. You can still get a clear sense of how time moves for the workers in Zhili in “Youth (Homecoming)” without necessarily knowing what comes next.