“White Nights” tells such a tortuous story there’s only one way to account for it: This screenplay was dreamed up to accommodate two dancers with little else in common. If the movie had allowed them to truly communicate about (and through) their dancing, that might have been enough. But “White Nights” has been made in a cynical world where it is actually believed that a dance movie will interest more people if it is also a thriller: a pas de deux between the CIA and the KGB, if you will.

The movie tells the story of a Soviet ballet dancer who has defected to America and an American tap dancer who has defected to the Soviet Union. The Russian is on a flight to Japan when the jet is forced to crash-land in Siberia, and so he is once again in the hands of the society he has rejected. The Soviets do not imprison him, however; they hope to score a propaganda victory by re-programming him to accept his Russian homeland once again. And one of the ways they hope to do this is to send him to live with the American dancer and his Russian-born wife.

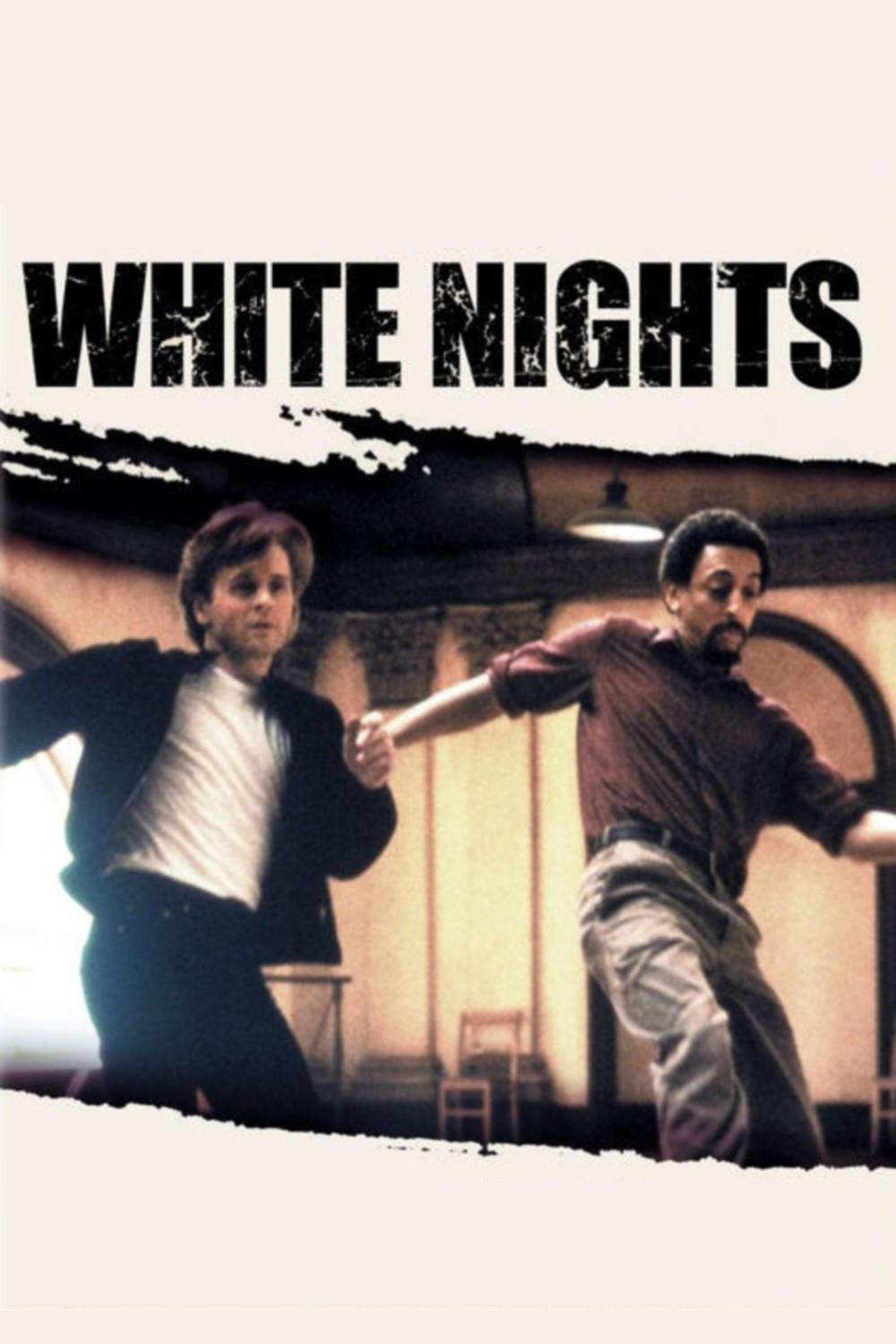

The Soviet dancer is played by Mikhail Baryshnikov, once of the Kirov, and the American is played by Gregory Hines, recently of “The Cotton Club.” It is tempting to wonder what sort of a movie might have resulted if they had just been allowed to dance for two hours, but that, I suppose, is too much to hope for. They do find time for several remarkable dance sequences in “White Nights,” and those are the major reasons to attend the movie. (The minor reasons include the luminous presence of Isabella Rossellini as Hines’ wife and the superior special effects in the airplane crash scene.)

Baryshnikov opens the movie dancing opposite Florence Faure in Roland Petit’s ballet “The Young Man and Death.” It is an extraordinary performance, filled with athletic grace, as in one dazzling moment when he climbs onto a chair back, rides it to the floor and continues effortlessly. Hines has a no-less-amazing sequence in which he uses words and dance to explain to Baryshnikov why he chose to leave the United States and settle in the Soviet Union. The moments when the two dancers are together on the screen are the moments when the movie is alive.

All around them, alas, is a drippy thriller plot, made out of recycled political intrigue. Jerzy Skolimowski, the Polish director of “Moonlighting,” plays a Soviet intelligence official who masterminds the would-be rehabilitation of Baryshnikov. As he attempts to spy and eavesdrop on the dancer’s activities, the movie takes on a kind of grim monotony that’s the opposite of the energy in the dances.

Incredibly, in a film filled with so much grace, the story finally comes down to an awkward action scene in which Baryshnikov, Hines and Rossellini try to slide down a rope to freedom. As nearly as I could figure out, two of them subsequently re-enter the very building they have just escaped from. Simultaneously, there is an unbelievable tactic in which the Soviet eavesdroppers are fooled by a tape recording. Give us a break.

There are two romantic relationships in the movie, which hardly has time for them. Hines and Rossellini are shown in an uneasy alliance: They know they love each other, but they have never reconciled the way they feel about their different societies. Helen Mirren turns up as Baryshnikov’s former lover, a dance partner he left behind without a word when he had the opportunity to defect. Now she is a powerful figure in the Soviet dance bureaucracy, the head of the Kirov, and he has a chance to rehabilitate his reputation by staging a comeback on her stage. As if the movie were not already cluttered, Geraldine Page has the thankless role of Baryshnikov’s American agent, forever hectoring the officials at the U.S. Embassy.

“White Nights” is made by people who seem much more comfortable with dance than with the requirements of the Hollywood thriller. It comes to life in the dance sequences, and then drifts away again. Watching it, I was reminded of nothing so much as those old Ed Sullivan TV shows in which culture was sugar-coated: Watch this ballet dancer, Sullivan would promise us, and Sophie Tucker will be out in a minute.