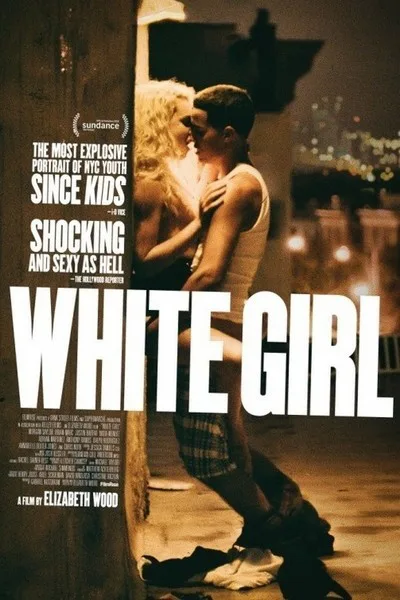

Leah (“Homeland”‘s Morgan Saylor) is not a “girl gone wild.” She’s already wild when “White Girl” starts, a first feature from writer/director Elizabeth Wood, and apparently loosely based on some of Wood’s experiences while she was in college in New York. “White Girl” is the story of the couple of weeks in Leah’s life before her sophomore year where she gets involved with Blue (Brian Marc), the Latino drug dealer who hangs out on the corner beneath her apartment window. Blue is busted for possession, and Leah—out of nowhere—begins a frenzied quest to move mountains (of coke, literally) to get him out of jail. She’s only known him for five days or so when he gets busted, so her maniacal devotion to him makes little sense, since she also barely seems to perceive him outside of the drugs he provides. Wood’s style is immersive and raw, although to what end is not clear. The characters are envelope-thin (except for Blue). Leah is a cipher, made up only of impulsive addict behavior. Maybe addicts are just their addiction, but it makes for somewhat dreary viewing when the lead character has no apparent personality. The scenes of wretched debauchery pile up, and in a film only 88 minutes long it’s a tough slog. It’s difficult to perceive what story is actually being told. There’s a lot to look at, colors, light, drugs and nudity, and much of it looks really good. But there’s nothing else to latch onto.

Leah has dyed her long straggly hair platinum-white, and her vampirish pale skin, white tank tops and tiny white sundresses make her look like a deranged wraith, floating through the about-to-be-gentrified streets of Ridgewood, Queens. She’s always either plastered or blasted out by a hangover the next morning. Leah is the “white girl” of the title (although there’s a “brand” of cocaine mentioned that has the same name). Leah is not an innocent naif who wanders into the underworld of Needle Park. She’s a college student with a summer internship at a “hip” magazine, where her reprehensible boss (Justin Bartha) offers her coke (which she promptly snorts up), and then proceeds to screw her in his office. Hooking up with Blue is part of her quest for drugs and excitement, a jagged break with her suburban privileged past. Leah is an addict (“I’d drink nail polish remover if someone gave it to me,” she says) and far more hardcore in her drug use than any of her drug dealer friends, who smoke weed but don’t touch the hard stuff they sell.

Her relationship with Blue starts out with stand-up sex on her rooftop, but Blue treats her with an almost formal and gentlemanly protection. He sees her as a sweet girl playing around with danger, and he’s worried she will get in over her head. He’s a transparent kid, with an open face, a quick and sincere smile, and he bonds himself to her pretty quickly. He is capable of intimacy. She is not. There is so much explicit sex in “White Girl” that you wonder how anyone has time to do anything else, but Blue feels something for her. He graces her with a nickname (“Shorty”), and wants to take her out for a nice dinner, Italian or something. Their relationship is the most intriguing part of the film, and that is due entirely to Brian Marc, a hugely gifted young actor. Saylor has a tendency (evident in “Homeland,” too) to “indicate” her emotional progression, one beat at a time. It makes for a stilted end result, and lots of unnecessary pauses as she walks us through that progression. Marc, on the other hand, has figured out for himself as an actor why his character would fall in love with Leah, what it is he senses in her, what he envisions in a life with her. When he says to her later with tears in his eyes, “How could I fuck up right when I met you?”, you believe him. You can’t take your eyes off of him.

Chris Noth shows up as a beleaguered lawyer, known for defending drug dealers, who’s willing to help out the girl with the long white hair who begs him to get her “friend” out of jail. He looks at Leah and clocks immediately what she is all about. He says to her, “It’s a fucked-up system,” noting the difference between what happens when a person of color is busted and a white person is busted. He does his best to combat that unfairness, and his office piled with case files looks like a hoarder’s paradise.

There are numerous nods to Larry Clark’s 1995 film “Kids,” in particular a scene between Leah and the lawyer, but mostly because of its portrayal of an urban environment as a pitiless wilderness where privileged unmonitored kids fall through the cracks. There are no true grownups in “White Girl,” although Blue is clearly a good man with, ironically, the only moral compass in the entire five boroughs.

What is the point, ultimately, of all of this? A personal catharsis for the director, maybe, which would explain her seeming lack of awareness that Leah does not come across as a person with recognizable motives, or an inner life outside of her immediate circumstances. There’s a voyeuristic aspect to the film: the nudity, the constant sex, the scene where Leah snorts a line of coke off of someone’s penis in a nightclub bathroom. Maybe this is an actual snapshot of the various cultures that meet up in New York. Drugs bring all the classes together. If Leah was more than her mane of tangled white hair, the story—whatever it is supposed to be—would reveal itself. Here, the story is only in Blue’s face. Unfortunately, that’s not enough.