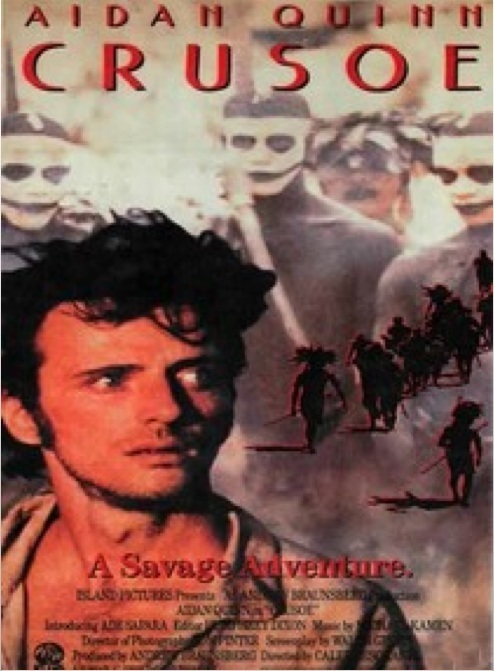

“Crusoe” is a film with a few important things to say and a magnificent way of saying them. It is a big, bold production, with the width of vision that sometimes develops when the director has a background in cinematography. Caleb Deschanel, who made it, needs few spoken words to tell his story, and probably could have done with less.

The film takes place in the slave-trading days of the 19th century, when a Southern aristocrat in need of money (Aidan Quinn) sets off on a risky venture to bring back slaves from Africa. His ship is caught in a mountainous storm at sea, and he is shipwrecked on an uncharted island where at first he believes he is alone – all except for a small dog who has also been thrown ashore. The dog becomes his link with society. The animal may not be able to speak, but at least it can listen, and recognize his voice, and care about him. He needs the dog very much, he discovers, and when it dies the scene is poignant and truthful.

In both the storm scene and the sequences with the dog, Deschanel seems inspired somewhat by Carroll Ballard’s “The Black Stallion,” a film he photographed. The sea, the island and the communion between man and beast are at least spiritually similar. But then the film takes a turn toward a more obvious meaning, as the man (named Crusoe, but not Robinson) finds that there are other humans on the islands.

They are “savages.” That is how he thinks of them. They conduct pagan ceremonies and would gladly kill him if they were given the opportunity. Spying on their rituals of human sacrifice, he saves an intended victim, nicknames him “Lucky,” and finds him dead in the morning. A few days later, Crusoe is captured in a snare set by another native, and that begins the real business of the movie.

This warrior (Ade Sapara) does not necessarily want to kill Crusoe. He simply wants some of his geese. But Crusoe is able to place only one interpretation on the situation and escapes to begin fighting the man. Their fight would lead to the death, but instead leads to a pit of quicksand, where the warrior must make a choice not determined entirely by his own lust for victory.

As a relationship gradually grows up between the two men, each one learns to accept the other as more or less his equal (prejudices die hard on both sides). And then a ship arrives from “civilization,” and Crusoe must make his choice. And that is all, really, that “Crusoe” contains: A journey, a shipwreck, the death of a dog, two encounters and a choice. Yet in telling this simple story at feature length, Deschanel never seems to pad, and indeed uses a lean, economical storytelling strategy.

His secret is that he can see. Many directors grow uneasy when long silences develop in their films. They feel something has to be happening every moment. There has to be a “plot.” Artificial climaxes must be contrived, leading to phony resolutions. Life becomes busier than is humanly possible. Deschanel, on the other hand, allows himself time to establish the mystery and isolation of his island and to show us the personalities of his characters, rather than have them impatiently describe themselves. The story takes on the weight and importance of something that has been really thought about, and that is why the ending has such meaning. The film has earned it.