“What Lies West,” a gentle drama about the budding friendship between a recent college graduate and a 16-year-old, is an original story by debut writer/director Jessica Ellis. But it feels like an adaptation, particularly of the sorts of very popular books about growing up in the suburbs that kids used to read in the late 20th century US, by authors like Beverly Cleary (for elementary school kids) and Judy Blume (harder-edged, for tweens and teens).

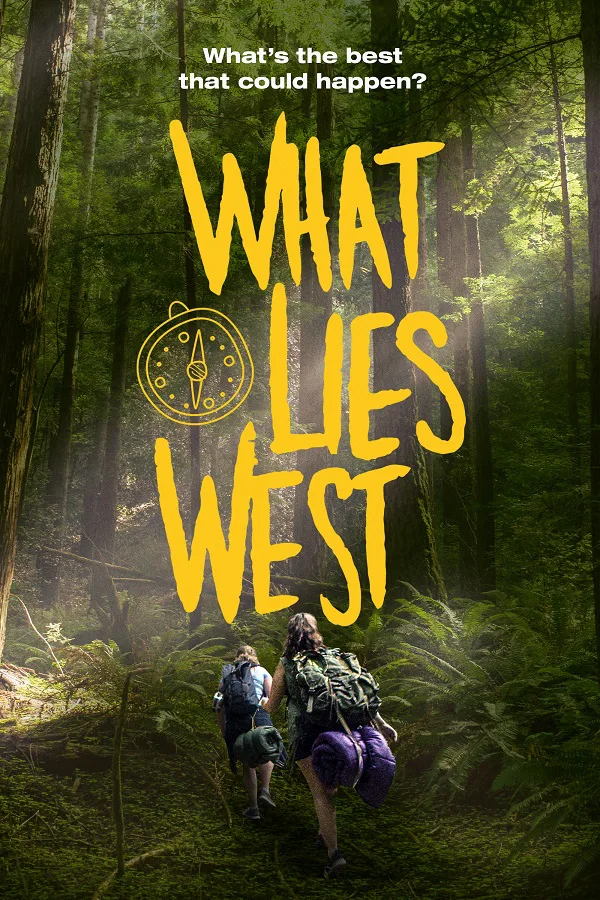

Set during the summer in hilly California, and building towards a long hike that tests the main characters, “What Lies West” is set squarely in the real world. The details of the central friendship and the characters’ relationships with their parents and peers ring true. But this not a high-stakes, deep-and-dark tale of emotional turmoil and loss, nor is it meant to be. Ellis has cleared out a space where almost nothing but the central friendship matters. Everything else in the young women’s lives is connected to that, but doesn’t define it. Uneventful in terms of action and jeopardy, to the point of opening itself to criticism that “nothing happens,” it’s a throwback to 1990s indie flicks that could build an entire self-contained (but compact) feature around one relationship, a few adjunct friends and family members, and a handful of available locations, and still get released, seen and appreciated.

What prevents this gossamer-delicate movie from evaporating is the complicated friendship between 16-year-old Chloe (Chloe Moore), an incoming high school junior, and Nicolette (Nicolette Ellis), a recent college graduate who has been hired to mind Chloe during the day while her single mother is working. Nicolette studied acting and has been invited to join a group of her college friends, who went to Hollywood instantly after graduation to “make it.”

She has chosen instead to stay in her hometown and work to save money while building up her image on social media, in hopes of becoming an Instagram “influencer” (which she believes will make her more cast-able when she does go to Los Angeles). Chloe is a sullen, nearly-silent girl when we first meet her, pretty clearly in (mild) rebellion against her mother Anne (Annie Peterson), who’s so wildly overprotective that you know she’s projecting her own traumas onto her child before she gives Nicolette a glimpse of her mania (a great scene, superbly acted by Peterson and the Ellis the younger). Chloe’s mute brooder routine starts to recede once she storms out of the house and walks into the park across the street, only to be followed by Nicolette, who is anxious and annoyed but not unsupportive. Nicolette seems conscious that the girl is being driven by forces not entirely within her grasp.

There’s a subplot involving Nicolette’s lingering crush on an ex-boyfriend, Alex (Jack Vicenty), the well-off son of a local restaurateur who is connected in showbiz (though probably not to the extent that he makes it seem while trying to mesmerize women). The stuff involving Nicolette and Alex is acutely observed, particularly the way Alex exploits his privilege and uses people. But it comes close to derailing the film’s focus on the central friendship in the first half of the film. (It feels like a stub from a different movie, maybe a sequel about Nicolette in Hollywood.)

Fortunately, the director settles in and focuses on the main duo as they prepare to undertake a 40-mile hike to the sea, following a route mapped out in a drawing by Chloe (and previewed in the charming animated opening credits). Ellis and cinematographer Sean Carroll focus on the characters and performances, though things open up visually once Nicolette and Chloe begin their journey (which is also a metaphor for their burgeoning independence from the expectations of others). Even without the underground theater/film tradition of giving lead characters the same first names as their actors, it would be clear from the lived-in performances by near-unknowns that this is a labor of love, built around the personalities and inclinations of the actors and crew. (“You haven’t left the house,” says Nicolette’s mother, by way of complaining that she hasn’t found a job yet. “That’s because the Internet exists,” Nicolette says, with a tone that suggests that she’s barely managed to prevent her eyes from rolling clear into the back of her head.)

It was never easy to get movies like this made and seen, and it’s no less onerous now. Even though technology has made feature filmmaking cheaper, and the process more easily understood/mastered, once you finish the thing you still have to compete for available eyeballs with a thousand other low-budget pictures made at the exact same time as yours. That’s not to mention the totality of social media, plus (literally) hundreds of streaming and broadcast TV series actively in production, most of them belonging to more commercial exploitable genres. Whereas 20 or 30 years ago, you might have had to compete with maybe a couple dozen low-budget movies of various types, in a far more robust theatrical scene, with more cities, a greater number of screening venue options, and local media outlets that were committed to reviewing everything that opened in town, thus giving the work more of a fighting chance to find viewers within the filmmaker’s lifetime, or (if one was lucky) when the VHS or DVD arrived in video stores.

That’s all neither here nor there, probably, and it’s nothing that Ellis has control over. It’s just a bit of context, and a longer way of saying that this is a likable debut, seemingly made with a specific audience in mind, and that it would be wonderful if it found that audience.