“Weeds” tells a story as old as the movies — the rags-to-riches saga of a troupe of theatrical amateurs who bring their show to Broadway — but it tells it with such a distinctive style, such a curious mixture of pathos and offhand wit, that it works for one more time. There’s never a moment when there’s much doubt about the outcome, but the movie gets there by a series of small delights and surprises.

The movie opens with the hero trying to kill himself in prison. He throws himself over a railing, but only breaks his arms. Then he tries to hang himself. No luck. He’s in for life, with no possibility of parole, and so in desperation he does something that’s even harder for him than suicide: He checks a book out of the prison library.

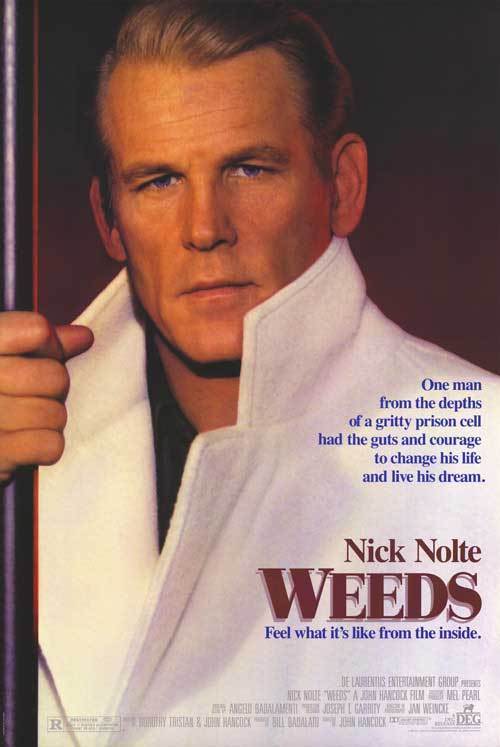

The prisoner’s name is Lee Umstetter, played by Nick Nolte with a certain weathered weariness and a way of hanging his head to one side and walking crooked. He’s a lifer with a broken spirit – until the books put ideas in his head and he writes a play in prison.

He decides to produce it, and the auditions provide a scene that’s a small masterpiece as one convict sings “The Impossible Dream” and another one recites “Eeny-Meeny-Miny-Mo,” which is the only poem he knows, and not a good one for prison recitals.

The play is a success, and a warmhearted, middle-aged drama critic (Rita Taggart) falls in love with Nolte and convinces the governor to commute his sentence. The rest of the movie involves Nolte’s attempts to round up his old prison friends, reassemble the troupe on the outside, and take the show on the road. First stop, San Francisco. Then Iowa, Illinois and Broadway.

The opening night off-Broadway supplies an example of how the movie finds surprises in familiar themes. We see a famed drama critic, drenched by a rainstorm, arriving late and trying to compose himself for the opening curtain. Will he be able to be objective? The movie gets such a big laugh with his arrival that we hardly care.

The opening night party at Sardi’s has more surprises, and the scene is stolen by Anne Ramsey, as Nolte’s ramshackle, but lovable, mother. And there’s another great moment, done with body language and a perfect double-take, when Nolte is so overjoyed he tries to kiss Ernie Hudson, one of his fellow actors, on the lips.

The troupe develops into a tight-knit band, played by Nolte, Hudson, Lane Smith, William Forsythe, John Toles-Bey, Mark Rolston and J. J. Johnson, with Joe Mantegna as a professional New York actor who joins them midstream and seems baffled by what kind of situation he’s walked into.

There is a real sense of community in their little group, which communicates itself even if the play they are performing does not. It’s usually the case with plays-within-movies that the plays seem less than convincing, although in this movie there’s a reason for that.

Unfortunately, the whole prison sequence at the end of the film also is less than convincing, as are the recycled ’60s leftist panaceas that pass, in that sequence, as electrifying truth-telling. It’s all a little too pat.

“Weeds” is a movie that is best when it observes small moments of human truth, and at its worst when it tries to inflate them into large moments.