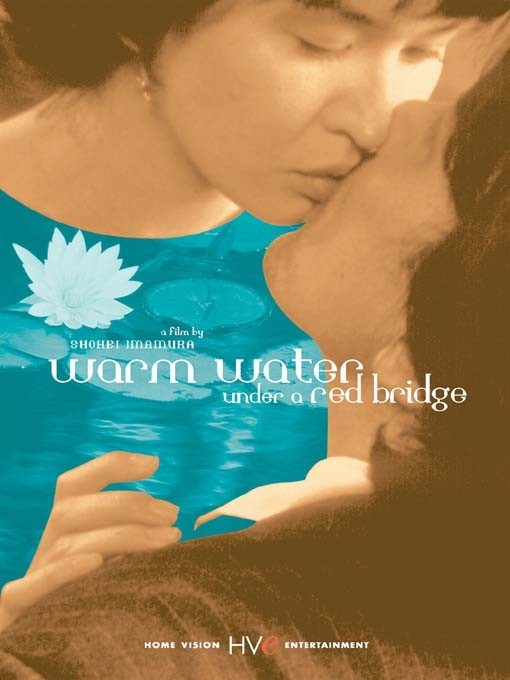

“Warm Water Under a Red Bridge” has modern automobiles and supermarkets, telephones and pepper cheese imported from Europe, but it resonates like an ancient Japanese myth. Imagine a traveler in search of treasure, who finds a woman with special needs that only he can fulfill, and who repays him by ending his misery.

Shohei Imamura, one of the greatest Japanese directors, tells this story with the energy and delight of a fairy tale, but we in the West are not likely to see it so naively, because unlike the Japanese, we are touchy on the subject of bodily fluids. In Japan, natural functions are accepted calmly as a part of life, and there is a celebrated children’s book about farts. No doubt a Japanese audience would view “Warm Water” entirely differently than a North American one–because, you see, the heroine has a condition that causes water to build up in her body, and it can be released only by sexual intercourse.

Water arrives in puddles and rivulets, in sprays and splashes. “Don’t worry,” Saeko (Misa Shimizu) cheerfully tells Yosuke, the hero. “It’s not urine.” It is instead–well, what? The water of life? Of growth and renewal? Is she a water goddess? When it runs down the steps of her house and into the river, fish grow large and numerous. And it seems to have a similar effect on Yosuke (Koji Yakusho, from “Shall We Dance?” and “The Eel”). From a pallid, hopeless wanderer in the early scenes, he grows into a bold lover and a brave ocean fisherman.

As the film opens, Yosuke is broke and jobless, fielding incessant cell phone calls from his nagging wife, who wants an update on his job searches. In despair, he hunkers down next to the river with an old philosopher named Taro (Kazuo Kitamura), who tells him a story. Long ago, he says, right after the war, he was stealing to get the money to eat, and he took a gold Buddha from a temple. He left it in an upstairs room of a house next to a red bridge, where he assumes it remains to this day.

Yosuke takes a train to the town named by the old man, finds the bridge, finds the house, and follows Saeko from it into a supermarket where he sees her shoplift some cheese while standing in a puddle. From the puddle he retrieves her earring (a dolphin, of course) and returns it to her, and she asks if he’d like some cheese and then forthrightly tells him, “You saw me steal the cheese. Then you saw the puddle of water.” All true. She explains her problem. The water builds up and must be “vented,” often by doing “something wicked” like shoplifting. It is, she adds, building up right now–and soon they are having intercourse to the delight of the fish in the river below.

This story is unthinkable in a Hollywood movie, but there is something about the matter-of-fact way Saeko explains her problem, and the surprised but not stunned way that Yosuke hears her, that takes the edge off. If women are a source of life, and if water is where life began, then–well, whatever. It is important to note that the sex in the movie is not erotic or titillating in any way–it’s more like a therapeutic process–and that the movie is not sex-minded but more delighted with the novelty of Saeko’s problem. Only in a nation where bodily functions are discussed in a matter-of-fact way, where nude public bathing is no big deal, where shame about human plumbing has not been ritualized, could this movie play in the way Imamura intended. But seeing it as a Westerner is an enlightening, even liberating, experience.

Imamura, now 76, is also the director of the masterpieces “The Insect Woman” (1963), about a woman whose only priority is her own comfort and survival; “Ballad of Narayama” (1982), the heartbreaking story of a village where the old are left on the side of a mountain to die, and “Black Rain” (1989), not the Michael Douglas thriller, but a harrowing human story about the days and months after the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

At his age, he seems freed from convention, and in “Warm Water,” for example, he cuts loose from this world to include a dream in which Saeko floats like a embryo in a cosmic cloud. There is also an effortless fusion of old and new. The notion of a man leaving his nagging wife and home and finding succor from a goddess is from ancient myth, and the fact that he would then turn to wrest his living from the sea is not unheard of. But throwing his cell phone overboard, now that’s a modern touch.