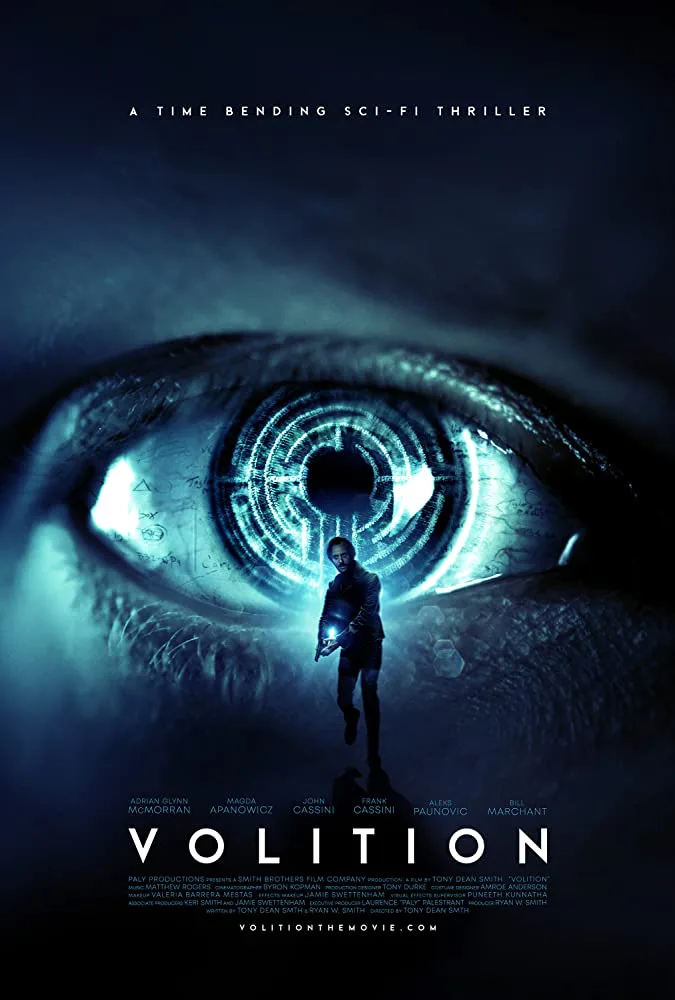

The uninspiring time travel thriller “Volition” begins with windshield wipers moving in slow-motion across a dark, rainy windshield. James Odin (Adrian Glynn McMorran), a hard-living clairvoyant, speaks: “They say when you die, your whole life flashes before your eyes.” A few excruciating seconds pass; the wipers wipe. Then James adds, “I wish it were that simple.” And it is: James, a sad, unshaven man with rings around his eyes and a heart of gold, tries to save himself and his optimistic love interest Angela (Magda Apanowicz) from violent gangsters.

There are a bunch of other plot twists for James to wrap his head around, despite his prevailing certainty that the future already is what it is. But the only theoretically complicating factors in James’ story—how can he see the future, let alone use that to save himself—are too easy to anticipate. “Volition” isn’t clever enough to get over this somewhat prominent obstacle, mostly because its creators go all-in on with their convoluted, but never complex story.

James’ quantum-physics-related problems begin after his surly landlord informs James that he’s four days late on rent. He now owes $500 by the end of the day. Doesn’t sound too bad, you might say. And you’d be right: James soon makes the money he needs using his ESP-like abilities. He can’t plan or control how long he sees the future, but he can usually make out the shape of things to come long enough to take some notes and make a little money. Still, James’ supernatural powers have understandably left him feeling drunk and jaded, a degrading condition caused by alcohol and a tragic childhood incident that turned James into a sad orphan, and then later a bitter adult.

Enter Angela, the sort of vaguely defined ingenue who’s new in town and enjoys drinking beer with James on his rooftop. Apanowicz delivers a fine enough performance, but Angela is more plot device than co-lead, let alone supporting character. When James says that “Our choices don’t matter. Life happens beyond our control,” Angela’s there with a dutiful, but unconvincing response: “That’s a shitty way of seeing the world.” James wants to buy what Angela’s selling, but he’s a little preoccupied with a diamond fencing scheme that’s (barely) planned by Ray (John Cassini), a tetchy hardware store owner, and Ray’s heavies, Sal (Frank Cassini) and Terry (Aleks Paunovic).

Here’s where matters become negligibly complicated. To solve Ray and therefore James’ money problems, James has to start talking to his nagging, eccentric scientist friend Elliot (Bill Marchant). Elliot warns James that he needs to try harder, in general, which explains why James has avoided him until the events depicted in “Volition.” But once James and Elliot do finally get together, some kind of plot begins, with James having to figure out a way to travel back in time, and save himself. There aren’t many surprises here, because the bread crumbs that lead to the movie’s big finish are plentiful and very stale. Seriously, the plot twists in this movie are so obvious and unappetizing that you couldn’t miss them if you tried.

And even if you succeeded, the biggest question posed by “Volition” would still be: So what? The movie’s ensemble cast are all believable enough in their respective roles, but director Tony Dean Smith and co-writer Ryan W. Smith don’t take them anywhere noteworthy. James retraces his steps right until something inevitably goes wrong with Ray’s diamonds. Then he has to retrace his steps even further, now with an ostensibly renewed sense of purpose: fix the diamond deal, or die trying. This cycle of events repeats itself, with some minor variations, until it becomes clear that the Smiths’ bigger ideas don’t meaningfully affect the shape or the substance of James’s story (ex: it’s unclear what Elliot does except keep the plot going). And while a complex narrative isn’t everything when it comes to science-fiction, it’s kind of important when your time-travel movie is focused on one man’s frustrated attempts at escaping his own private “Groundhog Day.”

Nothing in “Volition” seems consequential, because the Smiths barely pitch their narrative’s stakes. Their sketchy scenario always seems to be a few rewrites away from some place unexpected, but they never quite get there. So while there’s some talk in “Volition” about free will and the consequences of one’s actions, that all sounds like genre movie ballyhoo coming from stick figure characters like James, the kind of undeveloped hard-luck character who tries to establish his blue-collar bonafides by describing time travel as “Some quantum string theory bullshit about different events ringing out over space and time.” I wish “Volition” weren’t so simple, but it is.

Now available on digital platforms.