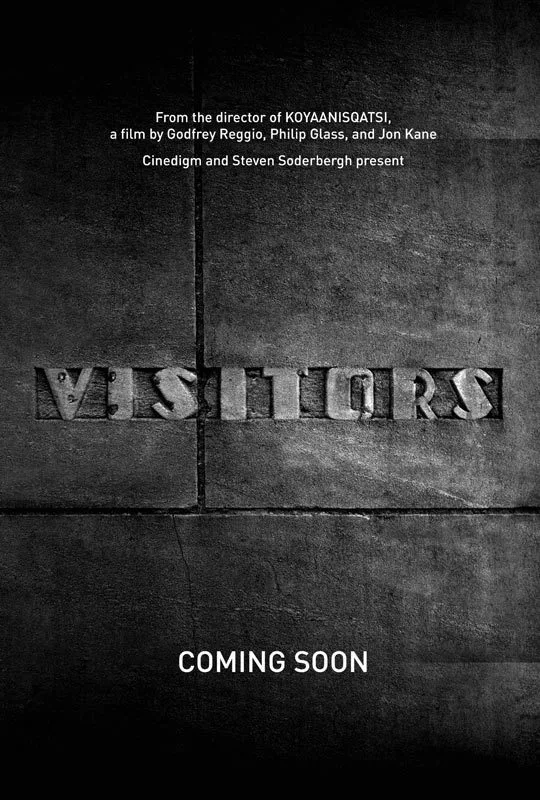

Godfrey Reggio’s experimental “Qatsi” trilogy (“Koyaanisqatsi” (1982) “Powaqqatsi” (1989) and “Naqoyatsi” (2002)) made visual statements about the violent ways man has brought technology to bear upon the natural world and his own race. They weren’t very subtle statements, but Reggio expressed them in kinetic images that kept your eye busy and often dazzled. “Visitors” is the first Reggio feature that feels more inert and random than purposeful and propulsive. Yet it’s refreshing for having mostly avoided the soapbox in order to concentrate on ambiguous imagery. It’s all in the title: based on the Hopi word for “life,” the Qatsi films added the Hopi terms for imbalance, transformation and war to hint that the modern world had become an unnatural disaster. But “Visitors”—what does that word tell us? We are left with a million possibilities and a stately stream of visual mysteries.

Yes, this is all plastic-bag-on-the-wind type stuff, and I wonder how much patience I would have for it without the hypno-music of Reggio’s longtime collaborator, Philip Glass. Glass’s signature repetitious motifs, always churning toward resolution yet continually denying it, carry us in suspense across shots that last minutes, not seconds. As form-fitting scores, go, Glass’s work for “Visitors” feels skintight. Reggio’s process includes making sure Glass is “marinated” in the film’s footage before writing a single note. It’s Glass who gives “Visitors” something like a structure, alternating between long, contemplative stretches and moments of ecstatic grandeur, like the crowd of sports fans who erupt in (extreme slow-motion) joy at some victory.

In a film flush with gorgeous black and white images, a sequence set in a swamp has stayed on my mind’s eye the longest since seeing “Visitors.” Ancient trees with the texture of lizard skin, leaves that billow or hang limp like hair and brackish water the consistency of lentil soup describe another world, smack in the middle of Louisiana. Here the filmmakers take an image familiar from a thousand National Geographic spreads and makes it new.

Two impulses struggle in Reggio’s work. He has often said that he intends his films to be non-intellectual and visceral, bypassing reason to achieve a physiological response. At the same time, a definite idea about The Way We Live Now always creeps into the process. In “Visitors,” Reggio expands on an idea pursued in his short film “Evidence“, in which children stared at television reflected off a two-way mirror. Behind the mirror was a movie camera—the viewer, essentially. In “Visitors,” people of all ages seem to stare at us while actually peering into computer screens and video games. It’s clear that Reggio finds something disturbing about that, but he lets Glass strike the tone of fascinated lament. The rest he leaves up to us.