There are images of astonishing beauty in Godfrey Reggio‘s “Powaqqatsi,” sequences when we marvel at the sights of the Earth, and yet when the film is over there is the feeling that we are still waiting for it to begin. The film is not so much a sequel as a continuation of “Koyaanisqatsi,” the 1983 film in which Reggio drew contrasts between the world of nature and the world of man.

In that film, he used speeded-up film to show us clouds climbing the sides of mountains, and then thousands of cars speeding crazily up and down the canyons of Manhattan. The message, I think, was that man has taken the beauty of the world and turned it into an overcrowded, environmentally insane travesty. The logical flaw in the film was that Reggio’s images of beauty were always found in a world entirely without man – without even the Hopi Indians whose word for “life out of balance” provided the title for his film. Reggio seemed to think that man himself is some kind of virus infecting the planet – that we would enjoy Earth more, in other words, if we weren’t here.

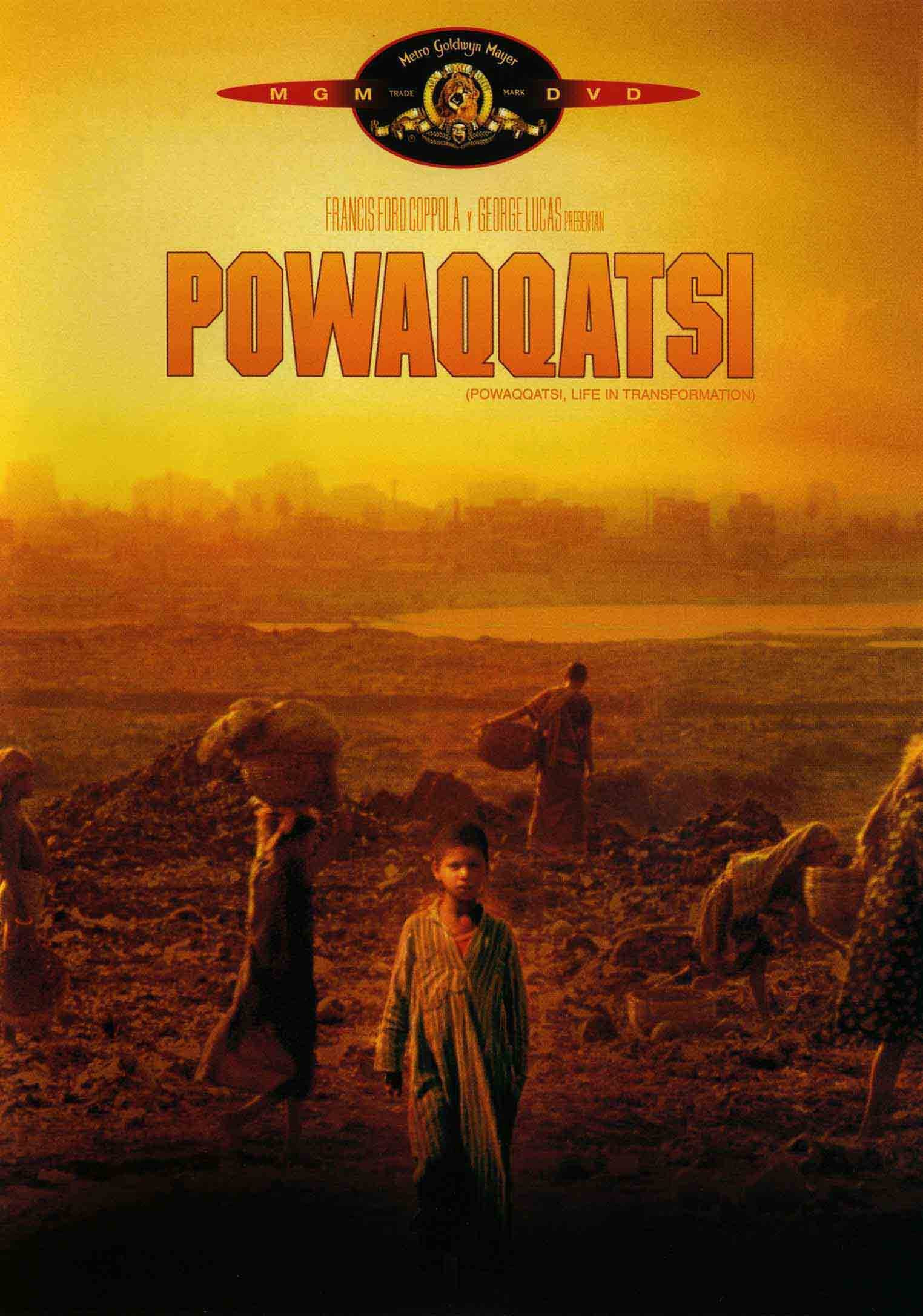

“Powaqqatsi” spends more of its time considering the tenure of men on the planet. It opens with a mesmerizing slow-motion shot of men laboriously slogging up an incline, bent double under the weight of sacks of mud on their backs. Their labor seems endless, their goal unclear – it is the task of Sisyphus. Then we see other extraordinary images. People living in the rooms of a building that has lost one of its walls, so that each household is like a display window. People washing in the streets, and in rivers, and in lakes. The contrasts between abject poverty and vast, impersonal mechanical processes, such as a freight train. The faces of people staring back at the camera.

Some of these shots are of surpassing beauty, especially the smiling faces of a row of children. And there is an aerial shot of a strange and remarkable building – some kind of temple, I suppose – that seems to be from another planet. I wondered, watching it, why I had never seen this building before. Where is it? What is it? The movie inspires a reverie like that. While the musical score by Philip Glass washes over the images, frequently in repetitive cycles, we watch the screen and see now this, now that, as if we were God leafing through the pages of a catalog for the furnishings of a new world. Sometimes we stir ourselves from our wondering torpor to ask what message, if any, Reggio is sending. The obvious one, once again, is that man is sinking into poverty and despair and bringing the environment down with him. But the beautiful color photography undermines this insight, confounding us again and again with images that seem filled with life, even as they pretend to be despairing.

“Powaqqatsi” is finally, essentially, a New Age music video, a series of images torn from context, scored, and edited to soothe us with their wonder while we idly try to pluck messages from them. I enjoyed watching the film and yet, finally, I think that was because I was lazy, and so was Reggio. “Powaqqatsi” is like the first step along a road that Reggio is reluctant to travel. Where is it leading him? What conclusions will he draw?