Jessie Reynolds is not the kind of girl who gets nice things written under her picture in the high school yearbook. She’s probably never going to graduate, for one thing. When we see her for the first time in “Virgin,” she’s trying to talk a stranger into buying some booze for her, and when he does, he gets a kiss.

Jessie is not bad, precisely. It would be more fair to say she is lost, and a little dim. She clearly feels left behind, even left out, by her family. Her sister Katie (Stephanie Gatchet) is pretty, popular, and a track star who dedicates her victories to Jesus. Her parents (Robin Wright Penn and Peter Garety) are fundamentalists, strict and unforgiving. Jessie doesn’t measure up and doesn’t even seem to be trying.

There is, however, someone she would like to impress: Shane (Charles Socarides), a boy at school. She wanders off from a dance with him, is drunk, is given a date-rape pill, is raped and wakes up with no memory of the event. When she discovers she is pregnant, there is only one possible explanation in her mind: There has been an immaculate conception, and she will give birth to the baby Jesus.

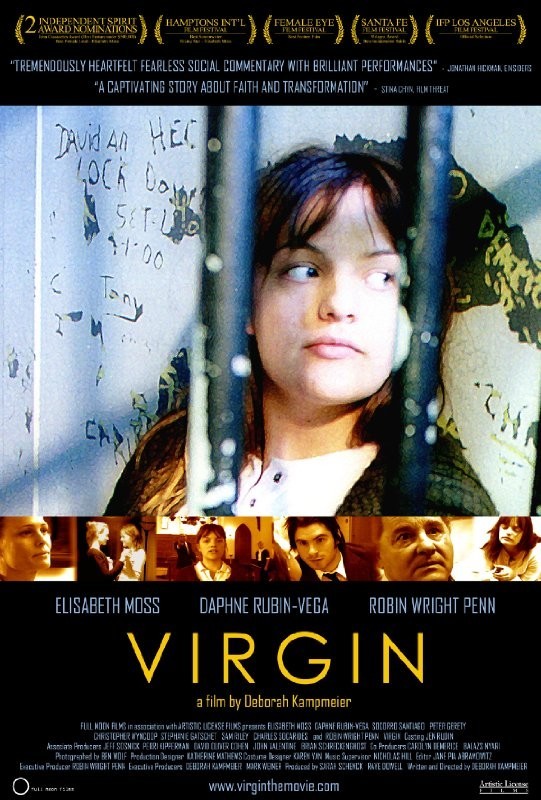

Jessie is played by Elisabeth Moss, from “West Wing,” as a girl both endearing and maddening. Her near-bliss seems a little heavily laid on, under the circumstances, but director Deborah Kampmeier has ways of suggesting it’s the real thing. Whether or not there is a God has nothing to do with whether or not we believe he is speaking to us, and although in this case there’s every reason to believe God has not impregnated Jessie, there’s every reason for Jessie to think so. Among other things, it certainly trumps the religiosity of her parents and sister.

Fundamentalists almost always appear in American movies for the purpose of being closed-minded, rigid and sanctimonious. Anyone with any religion at all, for that matter, tends to be suspect (the priest in “Million Dollar Baby” is the first good priest I can remember in a film in a long time). Movies can’t seem to deal with faith as a positive element in an admirable life, and the only religions taken seriously by Hollywood are the kinds promoted in stores that also sell incense and tarot decks. So it’s refreshing to see the Robin Wright Penn character allowed to unbend in “Virgin,” to become less rigid and more of an empathetic mother, who intuitively senses that although Jessie may be deluded, she is sincere.

There has of course been a great wrong committed here, but it would be cruel for Jessie to learn of that fact. How sad to believe you are bearing the Christ child and then be told, no, you got drunk and were raped. Better, perhaps, to let Jessie bear the child and find out gradually that like all children it displays divinity primarily in the eyes of its mother.

But Kampmeier is up to something a little more ambitious here. She uses visual strategies to suggest that Jessie, in the grip of her conviction, enters a state that is just as spiritual as if its cause were not so sad. The performance by Moss invests Jessie with a kind of zealous hope that is touching: Here is a slutty loser touched by the divine, and transformed. What has happened to her is more real than the miracles hailed on Sundays by results-oriented preachers.

The more you consider the theological undertones of “Virgin,” the more radical it becomes. Must you be the mother of God to experience the benefits of thinking that you are? Can those from a conventional religious background deal with your ecstasy?

There is a wonderful recent novel named The Annunciation of Francesca Dunn, by Janis Hallowell, a friend of mine, that tells of a waitress in Boulder, Colo., who a homeless man becomes convinced is the Virgin Mary. The novel explores a little more poetically and explicitly than “Virgin” the experience of being blindsided by an unsolicited spiritual epiphany.

Both works are fascinating because in mainstream society, there are only two positions on such matters: Either you believe, or you do not (and therefore either you are saved, or you don’t care). Is it not possible that faith is its own reward, apart from any need for it to be connected with reality? I am unreasonably stimulated by works that leave me theologically stranded like that. They’re much more interesting than works that, one way or the other, think they know.

Theological footnote: Every once in a while my Catholic grade school education sounds a dogma alarm. Jessie is not a Catholic, which perhaps explains why she thinks the term “immaculate conception” refers to the birth of Jesus, when in fact it refers to the birth of Mary.