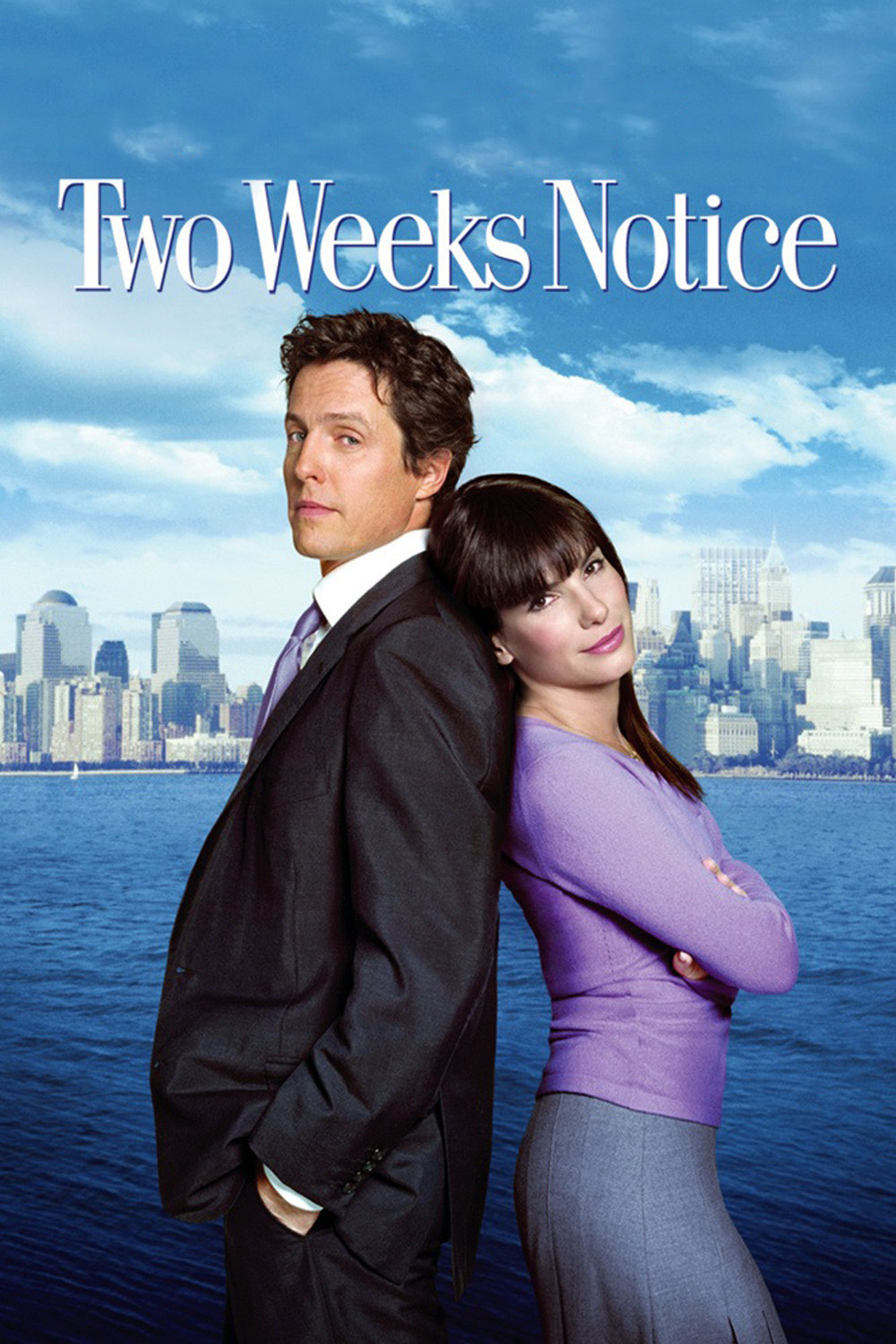

If I tell you “Two Weeks Notice” is a romantic comedy and it stars Sandra Bullock and Hugh Grant, what do you already know, and what do you need to know? You already know: That when they meet the first time, they don’t like each other. That circumstances bring them together. That they get along fine, but are sometimes scared by that and back off a little. That they are falling in love without knowing it. That just when they’re about to know it, circumstances force them apart. That they seem doomed to live separately, their love never realized. That circumstances bring them back together again. That they finally cave in and admit they’re in love.

You need to know: What her job is. What his job is. What they disagree about. What their personality flaws are. And whether, just when their eyes are about to meet, it is a woman who seems to lure him away, or a man who seems to lure her away? You also need to know certain plug-in details of the movie, such as which ethnic groups and ethnic foods it will assign, and what fantasy dreams it will realize.

I have not, by making these observations, spoiled the plot of the movie. I have spoiled the plot of every romantic comedy. Just last week I saw “Maid in Manhattan,” and with that one you also know the same things and don’t know the same things. The thing is, it doesn’t matter that you know. If the actors are charming and the dialogue makes an effort to be witty and smart, the movie will work even though it faithfully follows the ancient formulas.

Romantic comedies are the comfort food of the movies. There are nights when you don’t feel like a chef who thinks he’s more important than the food. When you feel like sliding into a booth at some Formica joint where the waitress calls you “Hon” and writes your order on a green and white Guest Check. Walking into “Two Weeks Notice” at the end of a hectic day, week, month and year, I wanted it to be a typical romantic comedy starring those two lovable people, Sandra Bullock and Hugh Grant. And it was. And some of the dialogue has a real zing to it. There were wicked little one-liners that slipped in under the radar and nudged the audience in the ribs.

She plays a Harvard Law graduate who devotes her life to liberal causes, such as saving the environment and preserving landmarks. He plays a billionaire land developer who devotes his life to despoiling the environment and tearing down landmarks. They disagree about politics and everything else. He is an insufferable egotist, superficial and supercilious, amazed by his own charm and good looks. She is phobic about germs, has a boyfriend she never sees, and thinks anybody who wants to hire her wants to sleep with her.

He is also impulsive, and after she assaults him with a demand to save her favorite landmark, he hires her on the spot, promises he will not offend her sensibilities, and gives her a big salary. He does this, of course, because he plans to violate all of his promises, and because he wants to sleep with her. He may not know that, but we do.

The first half of the movie is just about perfect, of its kind, and I found myself laughing more than I expected to, and even grinning at a colleague who was one seat over, because we were both appreciating how much better the movie was than it had to be. Then a funny thing happens. The movie sort of loses its way.

This happens at about the time the billionaire, whose name is George Wade, agrees to let the lawyer, whose name is Lucy Kelson, quit and go back to her pro bono work. Her replacement is June Carter (Alicia Witt), a dazzling redhead with great legs and flattery skills. We think we know that she is going to be a rat, and seduce George, and all the usual stuff. But no. She does make moves in that direction, but from instinct, not design. The fact is, she’s essentially a sweet and decent person. At one point, I thought I even heard her say she was married, but I must have misheard, as no romantic comedy would ever make the Other Woman technically unavailable.

Anyway, what goes wrong is not Alicia Witt’s fault. She plays the role as written. It’s just that, by not making her a villain, writer-director Marc Lawrence loses the momentum the formula could have supplied him. The last half of the movie basically involves the key characters being nicer than we expect them to be, more decent than we thought and less cranked-up into emotional overdrive. The result is a certain loss of energy.

I liked the movie, anyway. I like the way the characters talk. I like the way they slip in political punchlines, and how some of the dialogue actually makes points about rich and poor, left and right, male and female, Democratic and Republican. The characters are not entirely governed by their genitals.

Sandra Bullock, who produced the film, knew just what she was doing, and how to do it. Hugh Grant knew just what he was getting into. Some critics will claim they play their “usual roles,” but Grant in particular finds a new note, a little more abrupt, a little more daffy, than usual. And they bring to the movie what it must have: two people who we want to see kissing each other, and amusing ways to frustrate us until, of course, they finally do.