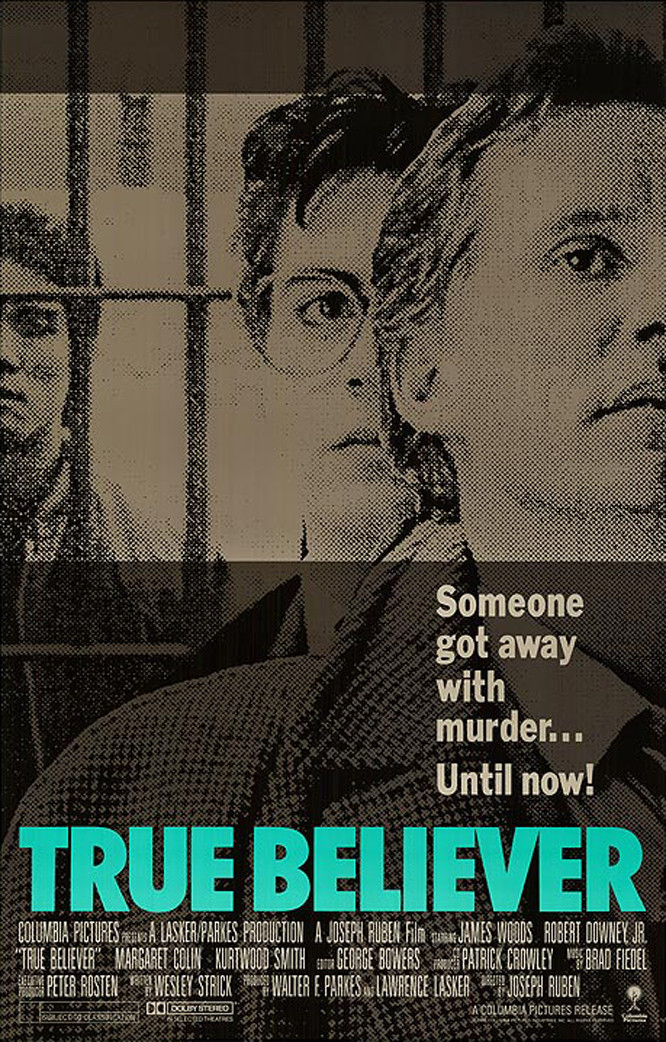

Let us now consider the case of James Woods, a name on that brief list of actors whose presence more or less guarantees that a film will be interesting. Woods works a lot. In the last year he has made “Cop,” about a dangerously out-of-control homicide detective; “The Boost,” about a salesman who gets swept away in the Los Angeles fast lane, and now “True Believer,” about a radical lawyer from the 1960s who has recently specialized in defending drug dealers.

The characters in these movies are not all the same man, although they all share some of Woods’ high-energy restlessness. The highflier in “The Boost,” for example, is not nearly as intelligent as Eddie Dodd, the fast-talking lawyer in “True Believer.” And yet all three characters are hypnotically watchable, because Woods talks fast and is always thinking, and his performances assume that the audience can listen and think as quickly as he can.

Does Woods tinker with the scripts he gets, or are they written with him in mind? In “True Believer,” he bursts into his walk-up office in Greenwich Village, says hello to his secretary, asks “What is this thing?” about a weird piece of sculpture standing in a corner, and disappears before he can get the answer. The moment has no purpose in the larger context of the movie, and yet it establishes the character and implies that this lawyer leads a larger life, with other concerns that began before the movie and will continue after it’s over.

Woods loves to pepper his roles with throwaways like that. It lends tension and texture even to plots that might seem standard in other hands. And the story in “True Believer” is a fairly routine version of the urban paranoia thriller, in which killers walk the streets because of corruption and compromise in high places. As the movie begins, Eddie Dodd is a burned-out pothead who represents drug dealers because they pay well, and usually in cash. He defends his practice by describing himself as on the cutting edge of civil liberties law, no matter that all of his clients are guilty.

Then a young man walks into his life: Roger Baron (Robert Downey Jr.), an idealistic lawyer who has read all about Eddie’s great cases in the ’60s and wants to sit at his feet and learn. Baron soon learns he’s the unpaid assistant of a cynic. But then a Korean woman walks into the office with a plea to Eddie: Her son has been in prison for eight years, for a murder he did not commit. Eddie’s instincts cry out to avoid the case, but Baron acts as his conscience, and before long both men are up to their necks in a dangerous investigation.

The case involves lots of flaws in the original trial: unreliable eyewitnesses, time discrepancies, conflicts of interest. In other hands, this material might seem familiar, but Woods puts a spin on it, an intensity that makes it feel important – to him, and therefore to us. And in the obligatory courtroom showdown that ends the film, Woods is able to find new ways to handle all of those old cliches about the surprise witnesses and the dramatic last-minute revelations.

Watching the film, I was not particularly impressed by Downey as the idealistic young law graduate. He seemed sort of indistinct, and I wondered why. Downey gave one of the best performances of recent years in “Less Than Zero” as a self-destructing drug abuser. What was missing here? A few days after seeing “True Believer,” I saw Downey again, in “Chances Are,” where he carries the movie effortlessly and with grace.

Seeing that second fine performance, I began to get an angle on Woods: He’s the kind of actor who has such high voltage, who’s so wound up, that maybe a younger actor tends to defer. We’ve all had that feeling of being in a conversation with someone else who has seized the advantage and kept it. Maybe working with Woods gives you the same feeling; it takes an improvisational veteran like James Belushi, his co-star in “Salvador,” to match his pace.

If you run Woods’ best performances through your memory – the ones I’ve mentioned, and “The Onion Field,” “Against All Odds” and “Once Upon a Time in America” – you see a certain pattern emerging. Woods doesn’t like dumb movies, and he doesn’t like to play dumb characters.

In the season of the Idiot Plot (the plot that doesn’t work unless everyone in it is an idiot), Woods makes movies in which the audience has to be on its toes to keep up with him. It’s quite an act, and when I see Woods on the screen in the first shot of a movie I sort of smile to myself because I know that something strange and offbeat and maybe even inspired is about to happen.