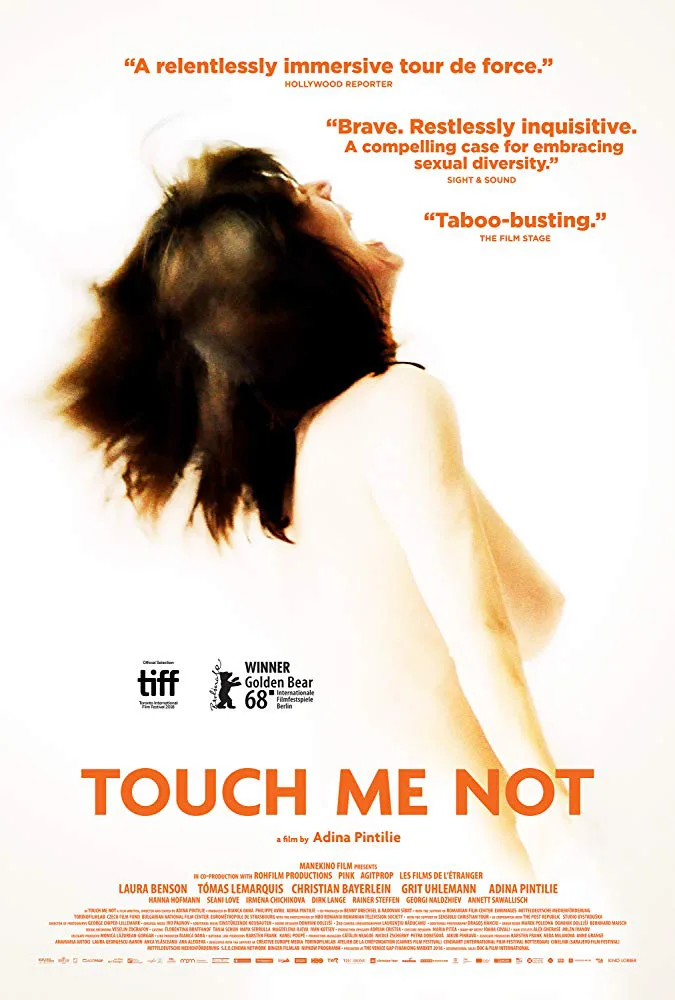

In “Touch Me Not,” the first feature from experimental filmmaker Adina Pintilie, and the surprise winner of the Golden Bear at last year’s Berlinale, a middle-aged woman (Laura Benson) attempts to break through emotional barriers to experience sexual pleasure and/or intimacy. Along the way, the film addresses things like ageism, transphobia, and the erasure of the disabled (especially when it comes to sexuality). Sex is a universal topic of interest, and has been so probably since before humans even developed language. Despite this, portrayals of single-minded sexual focus have a tendency to get super abstract, or over-intellectualized, or exploitative. “Touch Me Not” is definitely abstract and intellectualized, although I didn’t find it exploitative. But so much of the film left me cold, even bored.

There’s a lot of explicit sex and a lot of frank sex talk in the film. (I can’t tell you what you will feel about “Touch Me Not.” Tolerance for sexuality onscreen depends on the individual. What I find tiresome may be what you find fascinating, and vice versa.) Pintilie uses a blend of documentary and narrative fiction, meant to pierce through preconceived notions about what sex is, who “gets” to have good sex, how we perceive one another (or don’t) as sexual beings.

There’s a self-conscious voyeurism to the film. Laura is interviewed by Pintilie (seen on a monitor), so we are looking at someone being looked at, and also looking at someone who is looking. The issue of what it means to look and what it means to be looked at is a central theme, perhaps the most important. Many of the people in the film are non-actors. Many have disabilities. One of the recurring scenes is a group therapy session, where people are led through different exercises, similar to what happens in an acting class. Christian Bayerlein, a man with severe spinal atrophy who participates in these sessions, becomes the most memorable figure in the film. His therapy partner is Tómas Lemarquis, a man with alopecia who feels cut off from the world. Christian observes that Tomas’s soul seems hidden. When Christian speaks about his sexuality, he does so with a refreshing openness: “I love my penis because it’s the only part of my body that functions normally.”

In “Touch Me Not,” sex is not just about the act itself. It’s also about the issues around the act, the damage and unmanaged trauma people carry into the bedroom. Laura reaches out to experienced escorts and sex workers to grapple through some of these issues. (A sex worker friend of mine told me that more than half of her job was just listening to people talk to her. Her clients weren’t looking for sex as much as they were looking to abolish their loneliness, how invisible they felt to others.) Laura meets with a trans sex worker named Hannah, whom Laura finds “comforting.” Hannah transitioned at the age of 50, has a strong sense of who she is, loves her body, loves classical music. Laura also has meetings with a male escort named Seani Love, who specializes in “conscious kink.” Seani and Laura have conversations about boundary-setting, Seani asking questions along the way, constant check-ins. (If you want to see what sexy consent looks like, these scenes are a good example.) At one point, Seani reaches out, after asking Laura if it’s okay, and places his hand gently over her heart. He leaves his hand there. She begins to weep. I found these scenes, where I wasn’t sure what was planned beforehand and what was spontaneous, fascinating.

Pintilie’s style is repetitive. “Touch Me Not” rotates around the same three settings. There’s an almost monochromatic color scheme, with white backgrounds predominating, giving the whole thing a clinical hospital atmosphere. Laura tracks Tomas through the streets. People are seen from across a vast distance, through glass walls and windows. It’s very monotonous, but for no discernible reason. When Tomas follows a woman into a BDSM sex club, it was a relief to get a change of scenery, a place where there were dark colors and shadows and different people doing fabulously kinky things. Late in the film, Laura goes to visit her ill father in the hospital—the implications being that unresolved daddy issues may be the source of her sexual disconnection—an extremely trite “plot” development, a betrayal of the more nuanced explorations of invisibility, looking, being looked at, and how shame runs so much of our lives without our even knowing it. Catherine Breillat, in films like “Romance,” “Anatomy of Hell” and “36 Filette,” has covered the same territory, but Breillat’s films are ignited with urgency, anger, and curiosity. Lars von Trier’s “Nymphomaniac” practically lampoons these types of sexual-discovery films, while still treating the subject seriously. There’s humor in Breillat, there’s humor in Von Trier. “Touch Me Not” is humorless, an almost fatal flaw. The documentary-style sections—featuring Christian and his wife, Laura with the two sex workers, and the group therapy sessions—held my interest, but the rest of “Touch Me Not”—and it’s a long film—tried my patience.